In our fortress of analysis, set at a remove from the emotion-soaked, pressurized field of play, we design and refer to statistics that mostly zero in on how a player performed—attempting to cut through the haze of how that performance ultimately tangled with others and created a result. We do that—despite some dissonance over “what happened” and “what should have happened”—because in 99 out of 100 cases the focus on individual performance will provide a clearer roadmap to collective wins and losses.

And then there’s Jon Gray. The Rockies’ best pitcher was demoted to Triple-A over the weekend as 92 innings of baffling, horrendous results overwhelmed the numerous positive signs. Gray has struck out a career-best 28.9 percent of batters he’s faced, and walked 7.0 percent. His HR/9 is 1.08, middle of the pack among qualified starters and second-best in the Rockies’ rotation. It all adds up (or doesn’t) to a 2.78 DRA, a 3.07 FIP … and a 5.77 ERA.

When performance and results diverge, we call out: Come away from the din of the diamond. Hear this reassurance or warning. Sometimes, it brings comfort, and perhaps even expedites the merging of the paths. Other times, like this one, reality inexplicably drifts further and further off the supposed rails. There is still the crush of bad outcomes, ugly box scores, and urgent questions. Only now you can understand why the player, the team—everyone, really—might want to look beyond the typical vitals, just for a second. To be sure, you know?

***

Gray’s repertoire is built around a mid-90s fastball and a tightly wound slider that comes in close to 90 mph itself. A curveball in the lower 80s velocity band has also been incorporated more and more.

Given the enormous gap between his poor results and strong underlying skill indicators, there almost must be an obnoxious split or two that can carry you part of the way from 2.78 to 5.77, and maybe even toward the heart of the problem.

The first crumb for Gray was his performance with runners on base, specifically in double-play opportunities (runner on first, less than two outs). He’s faced 85 batters in one of this scenario’s various forms so far, and has allowed a slash line of (shield the eyes of the squeamish) .437/.500/.648. Arguably an even more bizarre part of this: Despite career and season ground-ball rates of better than 45 percent, he’s induced a measly two double plays. He got nine in his 93 cracks at the same situation last season.

Insult to injury: A run scored on one of the twin killings.

Balls in play are not supposed to work like this, and the models presume some level of sanity will eventually reign in that arena. Any level of normalcy would shave a noticeable number of runs off his total.

(The flip side of this coin looks like Cardinals starter Carlos Martinez, whose ERA is currently 2.32 runs better than his DRA. He has collected 11 double plays to help offset his league-leading proclivity for having runners on first base with less than two outs.)

Did this really fly off the handle with Gray along for the ride, though?

Perhaps the “runners on” portion of the split is not just an explanation for all the runs, but a red flag for the process involved? Does he struggle in the stretch? Well, the only difference between Gray’s “wind-up” and his stretch is a tiny step backward and some rocking and locking of the knees. If it’s altering his command in some way, the effect evaded my eyes.

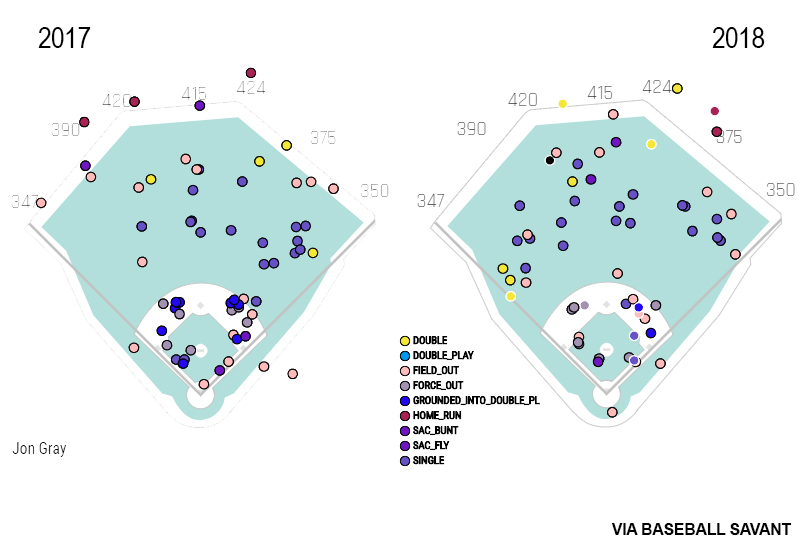

There are also no substantial reasons to lay the blame at the feet of his defense. Non-rotten luck would give him a couple more double plays, sure, but looking at the spray charts for 2017 and 2018, the first thing you notice is that the infield just hasn’t had as many chances to help him. He’s allowing more balls to fly over their heads.

Specifically, left-handed hitters are whipping his dominant secondary offering. In 2017, Gray’s slider induced a grounder 58.3 percent of the time lefties put it in play. This year, that’s down to 39.5 percent. The exit velocity on those sliders against lefties is up from 77.2 mph to 92.1 (!).

That just raises the question of why again. Gray has confirmed one apparent trend: He’s having trouble getting the slider down consistently. That low-and-away slider to righties, or low-and-in to lefties, is just missing.

“I’m trying to get the guy to swing and believe it’s going to be a fastball,” Gray told MLB.com in April, his campaign already feeling rocky. “But when you tense up and really throw, you’re trying harder but throwing the ball higher, and it gives the guy a chance.”

Against right-handers, he’s hustled around this by somehow turning his fastball into a ground-ball pitch, pounding the outside edge of the plate. Against lefties, he’s stayed with his fastball early in counts, and then attempted to get them chasing breaking stuff in the dirt when he can put it there. To his credit, he’s got one of the lowest contact rates in the league on chase pitches, which helps explain the improvement in strikeout rate. And, in a perverse way, whiffing often gives hitters another shot. Maybe Gray makes a mistake on the next one and … wham.

So, the stuff? Not apparently lacking. The placement? Clearly off.

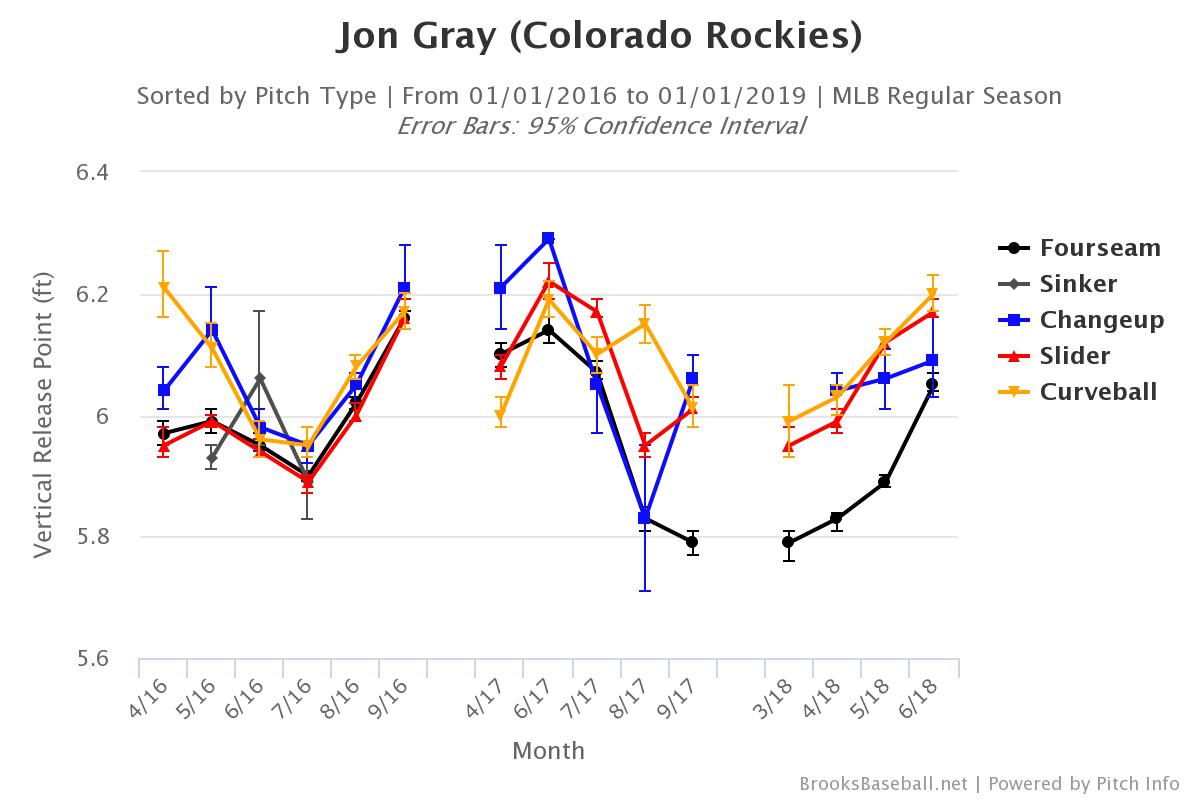

It gets more complicated from there. Mechanics good enough to strike out 11 batters per nine innings are tough to criticize, but there is one thing worth noting. It seems that toward the end of last season, and also when he came out this season, Gray was using a lower arm slot on his fastball than he had in the past, and indeed, lower than the slot he uses for his other pitches.

If that sounds minor, it might be. However, all these little things connect. That quirk of his fastball delivery might partially explain his slider’s troubles. As Gray said, he’s trying to get hitters to believe everything is a fastball. BP’s tunneling metrics help quantify how well he carries out that ruse when he, say, goes from fastball to slider. The more similar two back-to-back pitches look, and the longer they look that way, the more likely he is to get a whiff or poor contact from that slider.

Those fastball-slider sequences are grading out as less deceptive this season, particularly against the lefties who are mashing the slider. In 2017, the pitches ended up 13.4 times further apart at the plate than they appeared at the hitter’s decision point. That ratio is down to 12.3 in 2018. That’s not the end of the world in and of itself, but it provides a window into how the location difficulties and release point variance work in concert to create tangible effects: Lefties see the slider earlier this year. Perhaps it’s one reason lefties are hitting the slider harder.

***

What Gray can do in Albuquerque to get back on track is a tremendously significant quandary for the Rockies coaching and player development brain trust. We haven’t delved into the various effects of Coors Field and altitude, because a) Gray’s troubles have been equally present on the road, and b) those factors are consistent across his career. Yet part of the appeal of the minors is almost certainly the opportunity to run up pristine results, to inject positivity into the psyche while problems are ironed out. For a pitcher, there’s some risk this Triple-A assignment doesn’t provide much relief from the feeling of the field being tilted against him.

It seems like, as a player, you would want to fix something, even if it didn’t totally require fixing. Could you really shake the feeling of doubt if no tweaks were made, no suggestions acted upon? Gray is almost certainly working on something, like adding bite to the slider or finding a consistent release point. Filling up that lower corner of the strike zone for a few starts, collect visualization fodder. Something.

From afar, though, it’s appealing to think of this demotion as a symbolic flailing of the arms. Let the fog of confusion clear. Let him reset. Bring him back and wait for things to be different—to be the same as they ever were. Wait for normal to apply to Jon Gray once again. Hope this whole saga didn’t change Jon Gray’s normal.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now