In 2016, the Cubs traded top prospect Gleyber Torres and three other players to the Yankees in exchange for Aroldis Chapman, to whom they handed the ninth inning (and sometimes, once they reached October, the eighth and even seventh) as they made their run toward the World Series. That was a massive overpay, for a team that had other avenues through which to acquire quality relief depth and had virtually no other weakness. It was an overpay, especially, because Chapman was averse to pitching in situations other than the pursuit of a three-out save, and didn’t hold up well when asked to stretch himself in that regard. And because he was a free agent at the end of the season.

However, the Cubs chose to trade for Chapman because the Yankees were also selling the only other elite left-handed reliever on the trade market, Andrew Miller, and were only willing to do so at an even higher price. Miller was a bona fide multi-inning relief weapon, and had two more years of team control after 2016, albeit at a handsome salary. For Miller, New York wanted Kyle Schwarber as the first player in the trade package, rather than Torres (who is now a 21-year-old All-Star). The Cubs loved Schwarber, so they bristled, and they turned their attention to Chapman. The Indians ended up giving up both Clint Frazier and Justus Sheffield in order to land Miller.

There’s not really a Chapman on this year’s trade market. The closest facsimile might have been Kelvin Herrera, whom the Royals dealt to the Nationals in the middle of last month for a small fraction of the price Chicago paid for Chapman. Herrera isn’t Chapman, but he’s the comparable arm. He’s long-established, dominant, and a free agent come Veteran’s Day.

There might be a Miller out there this summer, though. One pensman with truly elite stuff and numbers is available in trade, and he has another year of control left after this one. He’s not even likely to make as much as Miller was making in 2016, given that he’s pitching this season under a contract worth $1.6 million, and that he’s not even closing for his current club. At age 29, however, Twins right-hander Ryan Pressly is as fully realized and dominant now as Miller was then. If the Twins decide to shop him over the next fortnight, they should be able to get more for him than any other team can get for any reliever who’s likely be dealt.

On Sunday at Target Field, Pressly entered in the sixth inning of the Twins’ final game of the first half, against the Rays. He struck out the side in the sixth, and then induced a lazy fly out when the Rays came up again in the seventh. He departed having faced four batters, fanning three, bringing his strikeout total for the season to 67—which matches his career-high for a full season, set in 2016. He headed into the All-Star break with serviceable but modest surface-level numbers: a 3.63 ERA, a 1-1 record, seven holds, and four blown saves. Dig deeper, however, and Pressly starts to look like an elite reliever.

The Big Four: Top-Tier Relief Pitchers by DRA- and cFIP, 2018

| Name | Batters Faced | cFIP | DRA- |

| Ryan Pressly | 197 | 58 | 38 |

| Edwin Diaz | 181 | 50 | 34 |

| Josh Hader | 177 | 58 | 36 |

| Aroldis Chapman | 154 | 61 | 40 |

No other pitcher with 40 or more innings this season has a cFIP as low as these four hurlers’, and no other pitcher has a DRA- as low as theirs, either. Pressly has become the most prolific true relief ace.

This has to be hard to process. You probably don’t even believe me. Before you read this, Aaron Gleeman will read it, and I bet he won’t believe it, even though he follows the Twins more closely than any other national baseball writer. He might even ping Rob McQuown, to make sure our numbers haven’t spun things sideways. They’re telling us, after all, that Pressly is a right-handed dead ringer for Josh Hader. They’re telling us Pressly, who has a 1.41 WHIP this season, is a sturdier version of Edwin Diaz, who might set the single-season saves record this year. It’s very hard to believe that the simple numbers can so convincingly hide a breakout as big as the one the advanced numbers insist Pressly is having.

Let me pitch this, though. Firstly, I can explain the poor overall numbers in three simple words: the Twins stink. They really stink. They’re 28th in Park-Adjusted Defensive Efficiency. They’re 19th in overall catcher defense. Pressly isn’t the only pitcher whose numbers are being distorted by playing in front of the injury-bitten, star-crossed, star-starved, unathletic Twins who take the field these days.

It’s not his fault that Byron Buxton and Miguel Sano have gone physically and developmentally backward, or that Joe Mauer’s injury issues have forced the team to let Logan Morrison play the field on a regular basis. It’s not his fault that Jason Castro had the rest of his season canceled mid-surgery, or that failures of both health and consistency elsewhere within the Twins’ staff have forced Pressly to carry one of the heaviest relief workloads in baseball, leading to several ugly, ERA-inflating appearances when he was likely gassed. All cFIP and DRA are trying to do is deflect the unearned blame basic stats would place on Pressly because of those things.

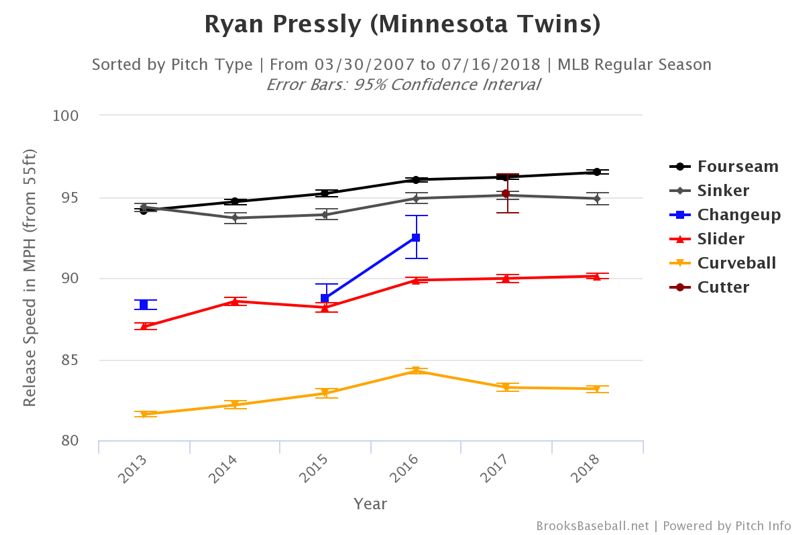

Secondly, though Pressly has always had good stuff, it’s getting better. Like, way better. He’s throwing both his four-seam fastball and his slider harder than ever, with the heater now sitting 96 mph and the slider sitting 90 mph.

That’s not the only fundamental characteristic of his pitches that has changed, either.

Average Spin Rate By Season and Pitch Type (per Baseball Savant)

| Season | Avg. Four-Seam FB Spin (RPM) | Avg. Slider Spin (RPM) | Avg. Curveball Spin (RPM) |

| 2015 | 2373 | 2103 | 2857 |

| 2016 | 2468 | 2574 | 2936 |

| 2017 | 2504 | 2628 | 3119 |

| 2018 | 2579 | 2746 | 3196 |

At the same time, he’s moved the release point on his fastball and slider much closer to one another, partially by moving toward the first-base side of the rubber and by lowering his arm slot slightly, but primarily, it would seem, by simply focusing on it. In the image below, each dot (of same color) further to the right is this season. Note how Pressly has stopped getting out around the slider, and is releasing it from almost precisely the same place from which he releases his four-seamer.

Our tunneling numbers speak to this. The average release differential when Pressly goes to his slider right after his four-seamer this season is much smaller than it was in 2017, and so is the distance differential when the ball reaches the tunneling point—the threshold at which the batter has to decide whether to swing, and which pitch he’s swinging at.

The ratio of the distance between the two pitches at home plate and the distance between them at the tunneling point is considerably higher, for both left- and right-handed batters, which means if and when they guess wrong they’re more likely than ever to whiff altogether. Pressly’s already thrown a slider immediately after a four-seamer to lefties 21 times this year, after doing so just seven times in 2017. He’s much more confident with that pitch pairing, perhaps because he’s now throwing them from the same slot, or perhaps because he’s better at burying the slider down and in to lefties.

All of this has conspired to give him an elite whiff rate, on both the slider and the fastball. Only four pitchers who have thrown at least 200 sliders have induced swings at a higher rate than has Pressly, and no pitcher has induced as many whiffs per swing on that pitch. Only Hader puts away batters at a higher rate when throwing his fastball in a two-strike count.

With those two pitches humming so harmoniously, his curveball has only gotten more devastating. That spin rate he’s ratched up near 3,200 RPM is the second-highest in baseball among guys who have thrown at least 100 hooks. He’s achieved unreal two-plane action on it, too. Check out this table from our PITCHf/x leaderboards. The only pitchers who can be said to have a similar amount of movement in both planes, and who throw the pitch nearly as hard as Pressly does, are Sonny Gray and Charlie Morton (unsurprisingly, spin masters in their own right). Pressly induces more swings with the pitch than either, gets plenty of whiffs when batters do swing, and can reliably get a ground ball with that offering (not true of the fastball and slider).

The track record of success isn’t long, but there’s ample evidence that this breakout is real. Pressly has three premium pitches, a year of team control after this fall, and a bargain price tag (at least financially). Some team should sneak in under the radar, ignoring the hype on Jeurys Familia and Zach Britton and shunning the huge ask for Brad Hand, and pay whatever it takes to add Pressly to their high-leverage relief corps. The Twins, in turn, should make sure they get a fair price for an extremely valuable player—but take the best offer they can get, eventually. This is a relief pitcher we’re talking about, after all, and one with both inconsistency and heavy usage still fading into the rear-view mirror.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now