Years ago, like, 25 years ago, I saw a cartoon of unknown origin and date. I don’t remember the name, but it stuck with me. The cartoon was about a (young???) baseball manager who wanted to bring in a relief pitcher. An older man, presumably a Gene Lamont-style bench coach, handed the man statistics on two of his relievers. I want to say the stats were batter vs. pitcher splits. One was really favorable, the other was extremely unfavorable. Basically the older man was trying to nudge him toward the using the pitcher with the worse statistics because they weren’t always predictive.

Oh, it’s entirely possible that this wasn’t a bullpen situation but instead bringing in a pinch hitter, and the numbers were against the current pitcher. I’d be shredded to bits on the witness stand here.

I really wish I knew more about it, because this was an era when Bill James was still a basement analytical cult hero not jumping feet-first online into a pile of rakes, and my recollection of it, which is foggier than Scotland in November, was that it was a cartoon for children that was vehemently anti-small-sample size. They were trying to tell us kids that drugs were bad, along with backwards hats, betting on baseball, and also apparently relying on these statistics.

The cartoon either aired on Nickelodeon or Cartoon Network. Those were my two choices back then. I remember where I was, though. My parents’ couch. Or possibly my own room. Either way, the conclusion of the cartoon was that the person with the worse split entered the game and the outcome was positive for the team. The older man then broke the fourth wall by reminding that statistics tell the story of the past but not the future. I am very sure it was about baseball. I am mostly certain about this. It was definitely not a badminton cartoon.

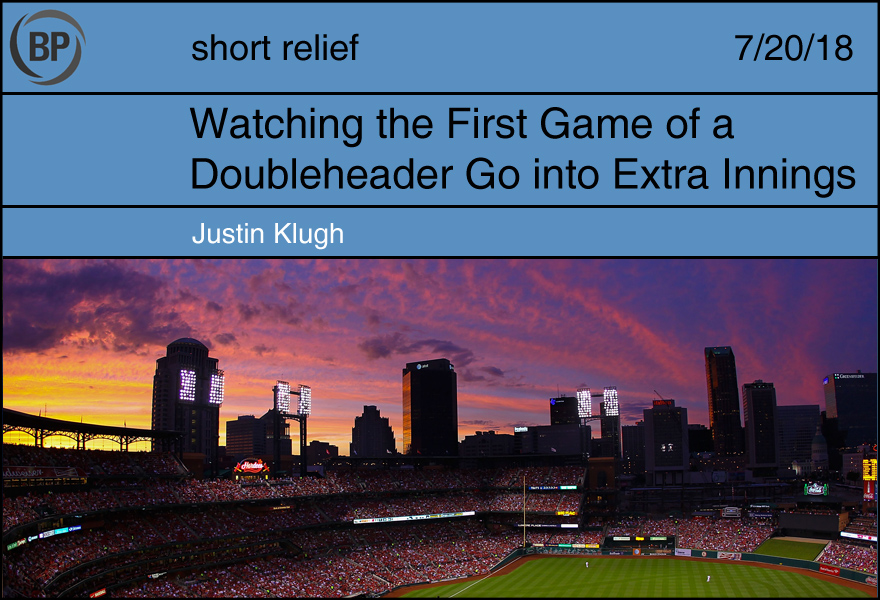

These teams are just good enough to score three runs apiece, but today, of all days, neither is good enough to score the fourth—each offense, utterly flummoxed by a back-end or spot starter. Each batter, swinging desperately for the fences not just to win, but to survive—to live. Each player, hoping not to see his name on the nightcap’s lineup card. Each reliever, wondering when the phone will ring, his name will be muttered on the other end, and the steward will point, sealing his fate as the game’s hopefully final casualty.

Each broadcast team, insulating their drooping willpower from the shrinking audience with increasingly nonsensical laughter.

“Hemmings takes ball two. He’s already walked twice today.”

“You know, I went for a walk outside the hotel yesterday.”

“Oh yeah? In those shoes?”

“Ah ha ha ha.”

“Heh heh.”

“Ha ha ha ha ha heh heh ha heh.”

“Ah ha-ah-ah–ah–ah–ah…”

The beer warms and flattens. The fans who haven’t liquified flee to the shade. The last dropped bite of a ballpark dog surrenders to the march of the ants. The catchers sit in smug, sweaty satisfaction, knowing it would take a human-rights violation for them to be penciled into the next nine innings.

And you, safe in the living room. But who knows who you will be by the time these games are over? My god… who are you now?

Just a spectator, miles away, slouched in resignation of your afternoon (and evening), a life lived between couch cushions.

But later—who knows! The phone calls you’ll have received. The tweets you’ll have drafted and deleted. The condition of our planet. Your position in the flow of the universe. As the innings pile up, fate could send you into a more effective or productive pursuit. That mostly-stolen sci-fi novella idea about a man who is targeted for a secret government training program for being good at bar trivia that everyone tells you not to write isn’t going to write itself.

And then, that sound! The ball travels slightly faster off the bat. The fans behind home plate rise, arms in the air. The broadcaster’s voice reaches its last crescendo, his energy and interest depleted, and all realize collectively this ball

isn’t

even

reaching

the warning track.

The left fielder collects it from the humid air.

Maybe just a few more, you think.

And then, nine more after that.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now