For many fans, to love baseball is to love it unconditionally. It doesn’t matter how bad one’s team is or how many disagreements one has with the minutiae of the game. There will always be the next game, the next season, the next great draft pick to root for. But loving baseball is not an unconditional practice; it’s just that those conditions are more easily met for some than others.

It’s easy to love something when your biggest gripe with it is that your team didn’t make enough moves at the trade deadline or clings too steadfastly to a player way past his prime. It’s easy to love attending games when you are surrounded by people who look and talk like you. It’s easy to dismiss criticism of something you love when that criticism does not impact you.

To be sure, Major League Baseball has always been far more exclusionary than inclusive, banning Black people and women early on in its inception. It has always limited the experience of playing and consuming to the fewest people possible without tipping into financial ruin. When it became economically beneficial, the owners lifted the ban on Black players; when it is economically beneficial, the sport advertises to women. And over the years, these tactics have succeeded, delighting a diverse array of children who flock to the game, innocent of its evils.

Over time, that innocence wears away, and the initial love and wonderment shrinks under the pressure of each domestic violence forgiveness, each standing ovation for bigotry. Somewhere in there is the game that captivated our imagination as children and provided us with friendships and fond memories, but it becomes harder to ignore that the thing we love does not love us back. Instead, each day, particularly in the social media age, we hold our breath, hoping that our favorite players and teams pass through unscathed, and we can love them just a little bit longer.

I’m fortunate in that I belong to the least marginalized of the marginalized. And yet I still go through this exercise, hoping that maybe if I hold out long enough or push back hard enough, Major League Baseball will stop hating me. For others, particularly queer POC, this hope is far more short-sighted, and the breaking point is much more imminent.

There are moments within each season that still bring us joy, and the process of talking about baseball still creates friendships that would otherwise not exist. But the daily barrage of disappointing moments obscures them, and where once there was excitement there now exists a perpetual weariness. We are constantly forced to work harder for something that is less worthwhile, praying that one day baseball will reciprocate the effort. Hopefully it won’t be too late.

Josh Hader’s got the support of his teammates and the weird, unwavering support of certain national writers, but his racist, homophobic, and generally hateful tweets will need more than an apology and sensitivity training to be forgotten by many. But not for some Brewers fans this past weekend, who proudly stood and applauded Hader’s first appearance since he apologized for his ignorant statements that remained undeleted for seven years.

Standing ovations are typically reserved for those who have returned after overcoming a hardship, a tragedy, an injury; perhaps they are a returning fan favorite who was traded. Let’s take a look back and rank standing ovations given by Brewers fans to see how this looks in context!

March 31, 2014: Ryan Braun’s return from a drug suspension was a polarizing issue, but Milwaukee fans made it clear that no matter what happened, they were happy to see their slugger back in the lineup. In his defense, Braun did NOT use hate speech, nor think so little of doing so that it never occurred to him to remove it from public view, despite rising in prominence as a professional athlete.

STANDING O RATING: Fans are going to back their guy, I suppose—but it’s easier to do so when he doesn’t disparage marginalized groups on his own accord and use the defense that he was only 17 at the time!

July 31, 2016: The biggest name on the trade market entering trade season, Brewers fans knew that their catcher Jonathan Lucroy was likely on his way out of town and wanted to let him know of their appreciation. Additionally, Lucroy did not say anything so heinous that his relatives at the game changed out of his jersey due to shame and humiliation, nor did he have to rely on national baseball writers immediately jumping to his defense by repeatedly and bizarrely referring to him as “childlike.”

STANDING O RATING: Nothing is more bittersweet than a goodbye (without using racist and homophobic language)!

August 9, 2014: Mike Fiers got a standing O for allowing a single run in eight innings, a huge comeback after getting blown out of his last MLB appearance, being demoted to the minors, and undergoing season-ending surgery. Fiers helped his cause by at no point offering a pathetic, publicist-crafted non-apology in the locker room following the revelation that he had frequently used a series of racist and homophobic phrases in a public forum.

STANDING O RATING: A letdown! A build-up! A comeback story! Zero racial slurs! This is why we watch baseball!

March 31, 2014: Hank the Dog, a former stray adopted by the Brewers during spring training, received a thunderous ovation on opening day 2014 just for being alive. Hank also endeared himself to fans across the sport by running around, wagging his tail, and not ever tweeting “white power lol,” “I hate gay people,” and multiple uses of the N word.

STANDING O RATING: Applauding Hank the Dog is why humans grew hands!

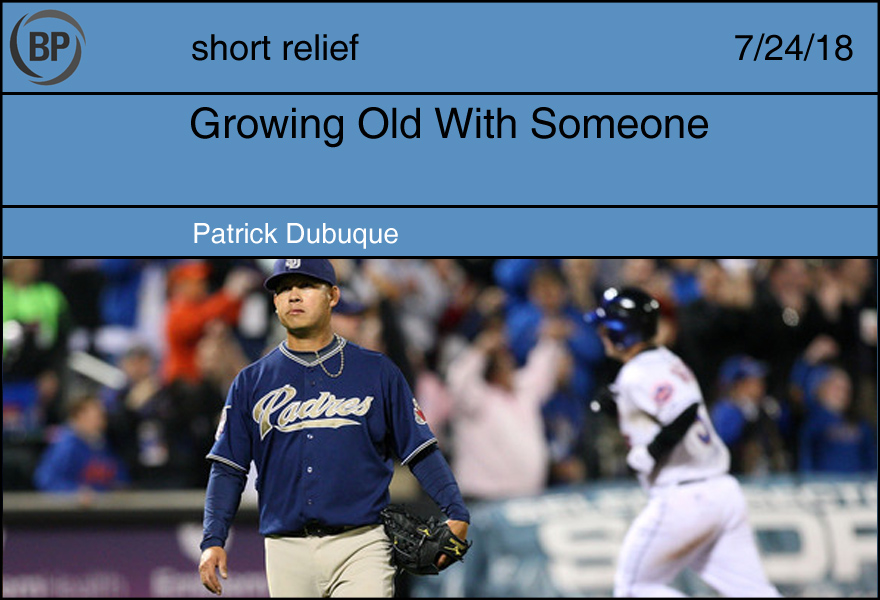

In a matter of days, I will be forty years old. It’s not easy to grasp this, mostly because age is, like many statistics, an average; my scalp and my soul hit middle age quite some time ago, while my public speaking skills still hover around college sophomore. I generally forget about my own birthday and round numbers don’t interest me that much, but there is one benchmark for my age that is far more disturbing:

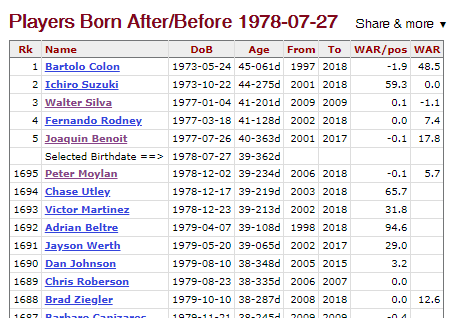

Five. Out of the thousands and thousands of men I’ve watched play, the smiles on baseball cards, only five men active in baseball are still older than me. Two of the five are essentially out of it: Benoit has been injured all year after signing a one-year contract with the Nationals, and Ichiro has perhaps one last overseas encore in him at best. Rodney and Colon have survived, well enough that I don’t have to worry about the final day yet. And the last… is Walter Silva.

It’s been nearly a decade since Walter Silva wore a major league uniform, and he didn’t do it for long. His career lasted 24.2 innings, or 24 earned runs, whichever you prefer. A decade before that, he was washing dishes at an Outback Steakhouse six days a week and playing semi-pro ball on Sundays in Los Angeles. After failing a tryout with the Tigers by throwing 88, he chose to move to Mazatlan to play full-time. He pitched as much as he could, played in the winter leagues with Adrian Gonzalez, who talked the Padres into giving him a tryout. This time, he threw 91, and it was just enough.

It was a dream come true, a dream he’d worked his whole life for. It was also a fleeting one. He struggled in the majors, he struggled in Triple-A, and soon he was home, pitching where they’d always let him pitch. Where they still let him pitch, ten years later; at 41, he has a 3.71 ERA for the Bravos de Leon. He speaks of his love of Leon, his adopted hometown, where he shares a clubhouse with Junior Lake and Felix Pie. He’s an institution in Mexico, their Bartolo, even as he’s a footnote here.

And that’s a shame. While Walter Silva turned out to be perhaps the by the very narrowest of margins a major league baseball player, he has come to be in among the grandest senses just a baseball player. Every once in a while we romanticize the Crash Davises of baseball, the Mantos and Hessmans, that interest never seems to cross the border. The quotes may be lost, but the stories themselves translate. After all, I can think of no better inspiration for a middle-aged man than someone who was told he was done at thirty, and just never listened.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now