On the west-bound edge of the turn lane, covers splayed and pages waving, a book. Some traffic-based injury—or the hands that jettisoned the book—dislodged a small chunk of pages, which lay a little more centered in the lane. What was knowable about the book in the few seconds it was visible as I drove by? That it was a thick book—easily in the 400-page range—that it was soft-cover, that it was imperial or royal octavo-sized, that it was likely perfect-bound. A perfect binding, meaning each sheet had been cut to stand alone, separately, and glued into the cover—a common tactic for modern paperbacks—rather than folded to form smaller folios of multiple leaves that are sewn together and then bound more sewing and often glue into a complete manuscript, might explain how the torn-out pages seemed so neatly done.

The drive-by offered no clues as to what kind of book, no possibilities about the content. Whether traffic or its previous handlers had broken its spine, I couldn’t say. I did consider stopping, picking it up, but it was nearly 4 p.m. and traffic was surfacing. I was also on my way to have a drink with a friend I see too seldom, despite the fact that we live within 15 miles of each other, and I didn’t want to be late.

Over two hours in a local restaurant’s near-empty bar, we talked about as little of the real world as we could manage, but of course, it creeps in. We talked about art and our aging pets and how cats will simply stop eating for no apparent reason, precipitating trips to the vet and inconclusive blood work and anxious trials of new foods, different foods, and if we’re lucky, said cat will simply start eating again for an equally unclear reason. We don’t know anything more, and yet we still feel grateful.

The Orioles have already been mathematically eliminated from the playoffs. While Baltimore wasn’t at the top of anyone’s prediction lists for the season, a season in which they will have pulled off a kind of miracle to end with fewer than 110 losses seemed also unlikely. But the 2018 Baltimore Orioles are having that kind of year in which everything and everyone craters at once; exempli gratia, in a game where they scored twelve runs on the powerhouse Red Sox, they still lost by seven. Some of the systemic failures can be explained—a lack of significant improvements in the off-season, the departure of the team’s few proper stars, the wrack of age and injury—and some of it can’t, not with the kind of surety that would make such historical failure easier to bear.

When I drove home two and a half hours after I’d noted the inexplicable book in the road, the whole discarded tome and all its scraps were gone.

There are only eight major leaguers who were born within a year of me. All of them debuted either this season or last season. This is a list that includes Juan Soto, Ronald Acuña Jr and Ozzie Albies. You generally have to be a special kind of talented to appear in the major leagues at or around the age of 20. Not only are they doing incredible things right now, but their best years are likely ahead of them, and there will likely be many of those best years. When you see Soto hit yet another homer, you see along with it all the homers that he could hit in the future, when he’s 25 or 27, when he’s hit his prime. When I watch these guys, I think along with everyone else: oh my god, he’s so young!

***

Juan Soto was the Nationals’ second-rated prospect before the season. Their top prospect was another one of the major leaguers born within a year of me: Victor Robles, whose birthday is May 19, 1997. Robles appeared in 13 games for the Nats last September. He hit .250/.308/.458 as the youngest player in the majors. This season, as Soto has put together what might be the best teenage season of all time, Robles hasn’t appeared in the majors. He hyperextended his elbow on April 9th attempting a diving catch in a Triple-A game. It was an incredibly ugly-looking injury. He could have torn a muscle or a ligament. He could have needed surgery; his arm could have been permanently damaged.

Luckily for Robles, and luckily for the Nationals, he suffered no structural damage, and sixteen days ago he was activated at Triple-A. He went 3-for-4 with a walk, a double, and a homer. This season was pretty much lost to him, but there will be so many other seasons. The body of someone that young has a remarkable ability for recovery, even from the most seemingly traumatic injuries. He’ll be fine.

***

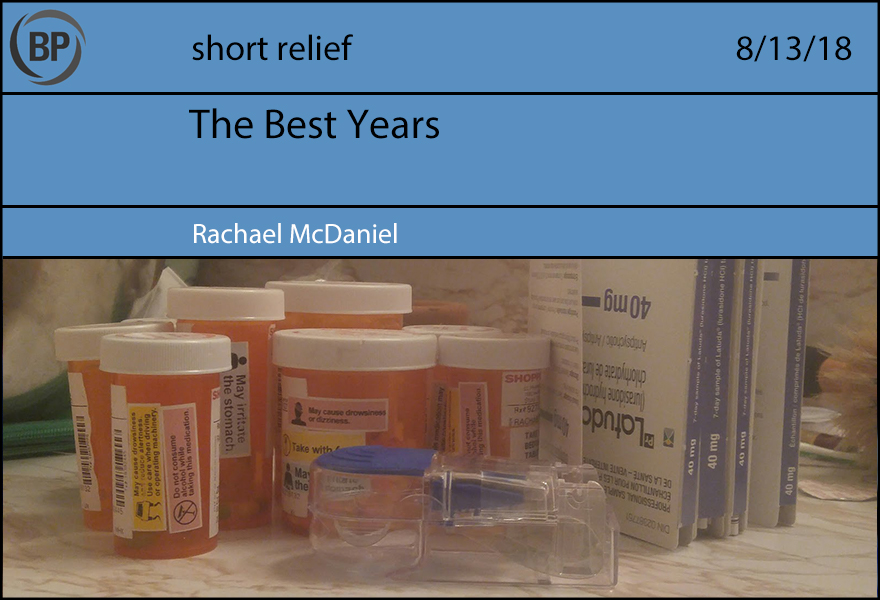

I had to buy a pill cutter over the weekend. It cost $10, which seemed an exorbitant price for a small hinged piece of plastic with a sharp blade attached to it. You open the hinge, and then you wedge the pill into this narrow gap, and then you shut the hinge, and there you go — two crumbling, powdery halves, relatively even in size. Being able to see inside them somehow makes them seem even less appealing. I have to do this for three different kinds of pill, and then I have to take them all with water and food, and then I wake up in the morning still tasting the chemical bitterness.

I’m 20 years old, and I had to spend $10 on this stupid thing to split pills in half so that I can dose them very specifically. Every evening, as the last baseball game of the day is winding down in the background, I mince my little blue and white and pink capsules. I have to do this so that I don’t die.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now