My son, age 10, looked up from his video game. “Wait, they aren’t letting King Felix start anymore?”

***

Once we reach a certain age, society allows us to ponder our mortality out loud. Too young, and we draw the concern and chastisement of our elders. Too old, and we’re perceived as giving up. Around life’s middle bits, however, we can settle in, and publicly consider what it means that we all invariably end.

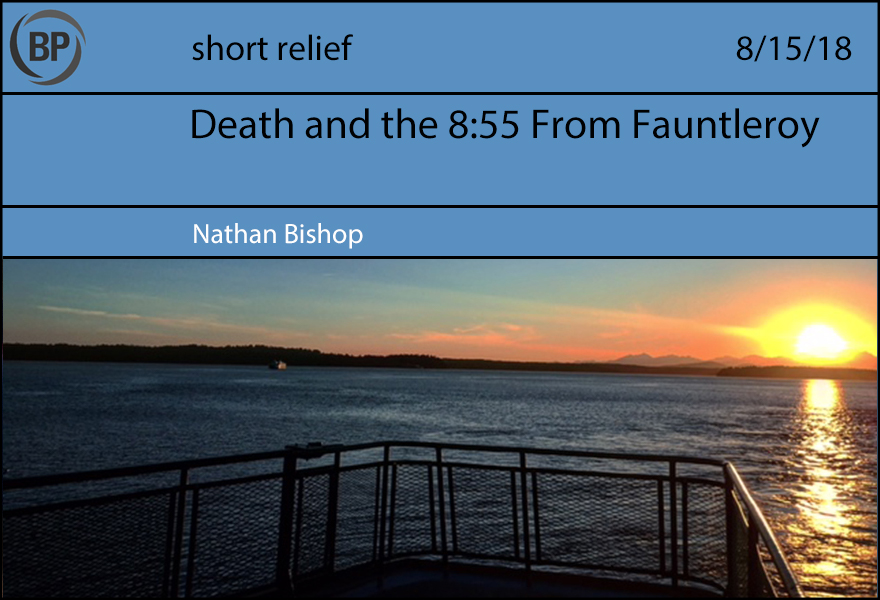

I was on the ferry, at dusk, alone. The day’s heat was actively breaking, and a cool marine breeze was gently cleaning everything it touched. I stood outside, watching the light slowly fade, and thought about death.

Natural beauty, the passing of seasons, years, millenia, and eons have always brought comfort to me when considering death. Observing a day’s passing on the Puget Sound, the rust peeking through caked on paint on the salt-worn ferry, the crystal blue sky’s descent into the fiery horizon, I let my mind wander.

I thought of the first man to push out a skiff into this water, and seeing what I was seeing. I thought of the time before man, when the sounds of the gloaming would have been pure, raw wildness. I thought of the future, far past my time, and felt a deep longing. In our Age of Disruption, when everything and everyone is seeking a new hack to skip, bypass, enhance, and upgrade life, I felt a resonant, primal need to allow the shorelines, hills, and waters I was viewing to develop how they would undisturbed, by their own means, and terms.

I felt small, and pointless, while also an inescapable, comforting sense that that was ok, because it was true. I felt the lure of death, and the promise of new life with it.

In that moment, briefly, somewhere between Vashon Island and home, I accepted where I was and, though I was in no hurry, where I was going. I was, for a small time, at peace.

***

“Well yeah, buddy. Baseball players get old, even the best ones. At some point you just aren’t good enough anymore.”

“How old is Felix?”

“Thirty-two.”

“Dad?”

“Yeah?”

“How old are you?”

We all know the second part of the quote. But I do, sometimes, wonder what it was like back then, the bricks rising, the wires dangling. Even mentioning it risks cliché, as if the very photos of the grass and the hardened men wearing dirt did not contain themselves, just out of sight, those new concrete idols to the gods of modernism surrounding the ballpark. But mediating this contradiction–the urban, the rural–is a constitutive part of baseball’s past, and, its present. We–as supposedly postmodern, post-enlightened subjects–nevertheless still often feel that tinge of nostalgia for a life before it all as we watch the sun set over the baseball diamond.

You’re there, now: The air begins to feel brittle, as if bending under the weight of the coming dark. For forty minutes the sun is frozen, stuck in the transition between night and day as if to offer a way out of that contradiction between modernity’s new life in the city and the smell of freshly-cut grass: it’s both, it’s neither. It’s ahistorical, ideological nonsense, but I eat it up, too.

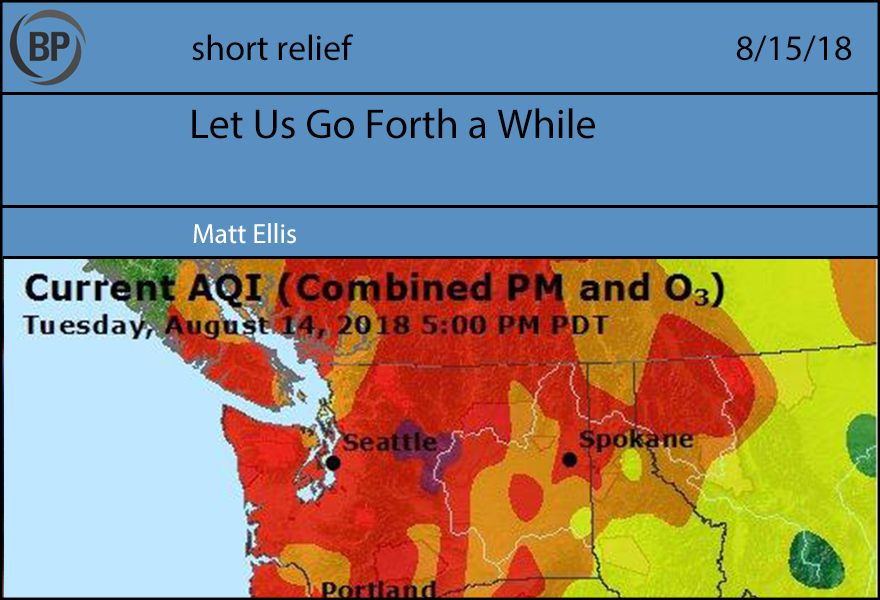

Summers aren’t what they used to be, though. One shudders to fret over baseball as the real victim of what’s coming, but it still comes to mind when thinking about going to games with my hypothetical children in twenty years. I think less about the ritualistic experience of going to the ballpark—a man sat in that very chair and saw Babe Ruth—as I do about them building that new stadium in Arlington, or another glass monstrosity in the state of Florida. I think about how, well, its always been hot down there and then I look at other places, and mostly I just think about how everything is different now, and I think about how I’m going to be saying that for a long time to come.

No one imagined that a quiet morning on a Cornish beach would change baseball forever. It all seemed rather normal for Wherrytown; the gray skies, the regal church steeples, the calming silence of a polite, industrious people. But as the sun rose, it became apparent that a swath of white, baseball-sized organisms had piled up on the beach, having mounted some sort of inexplicable, yet clearly successful, escape from the sea.

The mass migration perplexed the locals, even made the papers. But scientists defined them as “sea potatoes” with a wave of the hand and returned to their much more important work. Things continued as normal until one man, out for a stroll, stepped on one of them by mistake.

“Ouch,” it said.

“Good god,” came the reply of the passerby. “You can talk?”

“Of course we can talk,” said the sea potato.

“Why haven’t you spoken until now?!”

The potato shrugged, which looked very much like it did nothing at all. “Not much to say about a Cornish beach.”

Global culture reacted accordingly to the discovery of the, it turned out, rather talkative non-human beings. The same scientists returned, and with a second look realized that, ah yes, these were no normal sea potatoes. They were in fact self-aware, and assimilated quickly with the earthy populace. One night, sitting on two stools of a local pub, a pair of them witnessed the playing of a baseball game, recognizing immediately the abuse the ball was taking at the hands of humans who appeared not to care at all about its wellbeing–throwing it, clubbing it, tossing it in the trash.

They returned to the sea potato horde and informed them of the oppressive violence that others of their kind were receiving in this world. Together, they created a massive protest, demanding the rights of baseballs be recognized, the same as sea potatoes. Humans countered that baseballs, unlike the sea potatoes, were not sentient and did not feel pain or speak. The sea potatoes replied that perhaps they had not done so because, like the sea potatoes, they had never before been addressed.

With a huffy sigh, MLB commissioner Rob Manfred summoned a press conference, during which a baseball was placed across from him on a folding chair and greeted as though it were a human.

“Hello,” said Commissioner Manfred, humiliated.

“Well, howdy,” the ball said back.

The room erupted into silence.

The world had changed, and baseball had to change with it. Baseball responded with its typical brooding, and the regular season continued as if such a discovery could be at all ignored, until everything boiled over during a broadcast of Sunday Night Baseball.

“Hello,” a baseball said. “Pleasant enough evening, isn’t it?”

“Mmm,” said Max Scherzer, placing his change-up grip over its face.

“Your fingers are in my mouth,” the baseball noted. Scherzer did nothing to correct this, and instead went about his normal business of hurling a ball as hard as he could while screaming.

Flustered by the exchange, however, Scherzer surrendered a three-run shot that cost his Washington Nationals their last chance at the playoffs.

ESPN’s Matt Vasgersian was quick to question the ball’s timing for the conversation and Jessica Mendoza discussed how even small talk with the baseball can be distracting for a pitcher. Alex Rodriguez said that, while he was on the Yankees, George Steinbrenner would routinely gode a baseball into talking so that the players would know it was alive, then give it to a starved, ferocious dog he kept chained in the corner of the clubhouse.

“In my day,” came the refrain of “old school” types, “baseballs knew their place and kept their mouths SHUT.”

Of course, we all know what happened next: Baseballs created a union to protect themselves and organized a work stoppage that brought baseball to its knees. By that point, they had accepted the invitation of the sea potatoes to vacation in the quiet, seaside village where they had first emerged. Meanwhile, MLB tried and failed to negotiate with potential replacements, such as the, it turned out, much more profane and coarse tennis balls, and it took a laborious process to return baseball to a playable state.

While overseas, locals said that even having the dual populations of baseballs and sea potatoes around did not disrupt things too badly. They kept to themselves and enjoyed serene daily routines, admiring the sunset and shopping in the eclectic downtown. When asked what made them so at peace in the village, a baseball sighed and quite simply told an ESPN reporter with a shrug that looked very much like nothing, “Not much to say about a Cornish Beach.”

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now