There were 23 different players who recorded regular-season plate appearances for the 1992 Toronto Blue Jays. Of those 23 players, 22 of them recorded at least one hit. The regular lineup featured future Hall of Famers Roberto Alomar and Dave Winfield having All-Star seasons, but even the pinch-hitters and role players managed to make something of their extremely limited playing time. Rance Mulliniks, injured and in the final season of his career, recorded a walk and a hit in his three plate appearances; in eight trips to the plate, Domingo Martinez managed five hits. Even perennial bench-dweller Rob Ducey eked out a solitary hit over his 21 plate appearances that season.

However, there was one player among that group of eventual World Series champions who went to the plate three times for the Blue Jays that season and never once reached base. His batting line stands alone—a perfect, empty .000/.000/.000.

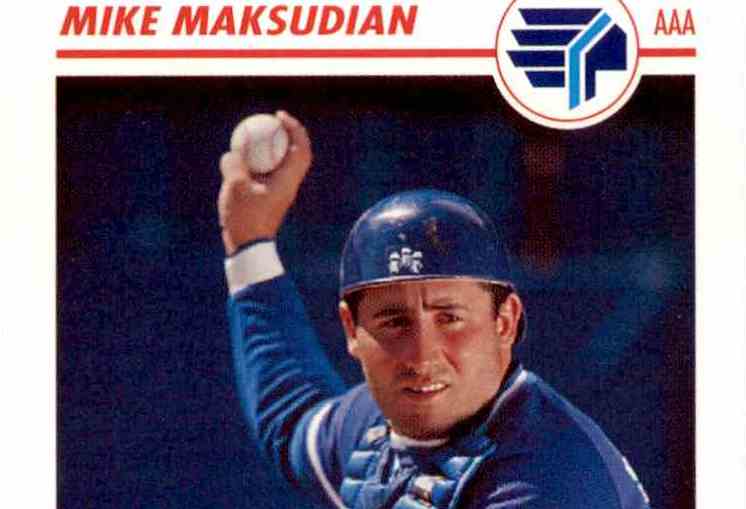

That season was his first in the major leagues, and his last for the Jays. He would go on to play a grand total of 31 more games in the big leagues, accruing 0.2 WARP over the course of his eight-year professional baseball career. He also became the center of a controversy surrounding players hugging each other, survived a midseason stabbing at a bar in Edmonton, and devoured at least one live locust (and possibly a small lizard). His name was Mike Maksudian, and on that team full of All-Stars and legends, his career might have been the strangest one of them all.

***

Mike Maksudian’s road to the major leagues was something of a non-linear progression. A Sun Belt Conference MVP in his college days playing for the University of South Alabama, he went unsigned after his senior year, eventually joining the White Sox as a free agent. He batted .349/.442/.532 in 34 games for the GCL White Sox in 1987. The next season he was one of the Midwest League’s best hitters, batting .303/.404/.423 over 102 games for the South Bend White Sox. That performance earned him a midseason promotion to the Florida State League, where he played only one game before he was traded to the Mets organization. Maksudian struggled in his 14 games with the St. Lucie Mets, and when the Mets presented him with the choice to be demoted or be released, he chose the latter rather than taking the perceived step backward.

At first, Maksudian pursued a career adjacent to baseball instead of one on the field. He found a position in the front office of the Birmingham Barons, a team he might have eventually played for had the White Sox not let him go. It didn’t take long for him to get bored of being a business manager, though, and before even a year had passed, he signed a contract to play the 1989 season with the newly-formed Miami Miracle, an independent team in the FSL. In his two previous years, the vast majority of Maksudian’s games had been played at first base, with a few sojourns at catcher. With the Miracle, though, he showed some positional versatility—while he played a few games each at his two familiar positions, he also played some third base. The majority of his appearances came in the outfield.

To go along with his newfound identity as a multi-position utility player, Maksudian had his best showing yet at the plate, batting .313/.371/.497. His performance attracted the attention of the Blue Jays, who signed him in the minor-league draft that offseason. Maksudian acquitted himself well in his 1990 Double-A debut, batting .287/.364/.419, and in 1991 he acquitted himself even better in his first crack at Triple-A, posting a .330/.393/.485 line and splitting time between first base and catcher. As a reward for his efforts, the Jays sent him back down to Double-A. No matter how well he might have been doing at the plate, Maksudian was “maybe ninth or 10th” on the Jays’ catching depth charts. He was 25 years old, not considered a prospect.

His plate appearances in Syracuse were better spent on other players—people the Jays were actually interested in developing. Back in Knoxville, then, in the exact situation he had once left baseball to avoid, he struggled, driven to prove himself to be something worth paying attention to. ”I was trying to do something extra,” he later explained. “I thought I should be hitting .400 or something there, and I pressed a lot.” In 1992, Maksudian finally got his chance. A series of injuries to the Jays’ catching depth left him as the starting catcher in Syracuse, and he had yet another good season: a .280/.344/.451 line over 373 plate appearances. ”Maybe now, someone will realize I haven’t been a fluke,” he said in late May of that season.

And while he would indeed end up getting his break into the majors later that same season, what might have prompted Maksudian to finally get called up was something extremely fluky: the fact that he hit four pinch-hit home runs that season. As the Jays entered the stretch run, neck and neck with the Orioles and with the Brewers not far behind, they figured they could use a clutch lefty hitter off the bench in the late innings—someone who could come in for an at-bat in the eighth or ninth, and who was versatile enough to slot into a variety of different positions should the need arise. On August 30, right on time to be eligible for the Jays’ postseason roster, Maksudian was called up to the big leagues for the first time.

***

Quite literally as soon as soon as he was called up, Maksudian somehow managed to draw media attention to himself. He was to join the Jays at home in Toronto, a country to which he had never been, and he found himself disoriented not only by the new experience of being in a major-league ballpark, but by the unfamiliarity of the environment itself. After signing his contract in the Jays front office upon his arrival in the city on the 31st, disoriented by the apparently labyrinthine halls of the SkyDome, he tried with difficulty to make his way back to the clubhouse.

“I finally found the clubhouse door and turned left instead of right when I got inside,” he narrated to reporters later. “I’d never been there but what I found was the players’ lounge, not the locker room, and there were a bunch of veterans hanging around. I acted like I knew where everything was, opened a door and walked right in.”

The door he walked right into was a closet door. It was an unfortunate opportunity for punnery that the local newspapers weren’t about to let slide—“Mike comes out of the closet,” the headline reads. The veteran players who witnessed his gaffe in silence probably didn’t let it slide, either.

But who among us hasn’t done something similarly idiotic in the anxiety of trying to make a good first impression? It made for an immediately endearing story, a change of pace from the coverage of the Jays’ ever-tenuous grip on the division, the constant stream of criticism for the team and its management. And after Maksudian’s years of baseball instability, after admittedly being surprised to have been called up at all, it seemed like he had instantly found himself a role on the team—as the jokester, the mood-lightener, the comic relief. Maksudian himself said that he was “trying not to look at this as a once-in-a-lifetime type thing, but that I’m part of the team … that I deserve to be here.”

He was going to continue to act the way he had always acted. And that meant he was going to be the guy willing to do whatever dumb shit the moment called for.

***

The first of Maksudian’s three plate appearances with the Jays came on September 2. The Jays were hosting the White Sox, and despite having out-hit them 12-5, they were down 3-2 in the bottom of the ninth. With right-hander Roberto Hernandez coming out for his third inning of relief, the Jays chose to pinch-hit for Alfredo Griffin. Maksudian popped out to the shortstop to lead off the inning. His second plate appearance would not arrive until September 11, but in the intervening days, Maksudian became legendary nonetheless.

The story goes like this: On September 8, 1992, the Jays were playing in Kansas City, an environment that has been known to feature the occasional large insect. There were a number of grasshoppers hopping around in the bullpen, and thus someone offered Maksudian $1.50 for him to eat one of the small ones. To the great delight and disgust of his teammates, he obliged. The stakes were raised—a large grasshopper, this time. Again, Maksudian was unfazed. Finally, as the Jays ran off the field to the clubhouse celebrating a 5-0 win, Devon White provided the ultimate challenge: a four-inch-long live locust he’d found roaming the center field grass. The prize for successfully consuming the locust was a cool $800. And after a few minutes of psyching himself up, Maksudian—quickly earning himself the nickname “Mad Mak”—actually did it.

His teammates were amazed. “I’ve never seen anything like that before, and I’ve been around a long time,” said Dave Winfield, who at 41 had indeed been around a long time. Maksudian, now $800 richer for his troubles, happily provided his insect-chomping strategies: “You have to pretend it’s a strawberry or something sweet and eat it fast so it doesn’t wiggle around.” His rationale for the sudden turn to entomophagy, though, was not a desire for riches, or a simple taste for bugs, or even really to earn anyone’s respect. “I just do it to keep everyone loose,” he said. “I have a limited role on the club, but we’re coming down the stretch and it might help.”

In Maksudian’s second plate appearance, he grounded out to lead off the ninth in a 4-3 loss to the Rangers. His final plate appearance came on October 4, the last day of the season—an eighth-inning pop-out. The Jays won that game 7-4. It didn’t matter, though. The pop-out didn’t matter, and the win didn’t matter, either, because they’d already clinched the division title with their win over the Tigers the day before—a day which also happened to be Winfield’s 41st birthday.

The dual celebration was raucous, and its most indelible image was this, narrated by the Toronto Star’s Dave Perkins:

Mike Maksudian, to this point better known as a man who will eat anything on four, six or eight legs to win a bet, reached skyward and turned a full beer upside down on the head of Dave Winfield.

“Thank you. Thank you,” Winfield said, and turned to see who was administering the celebratory shower. “Hey, the Orkin Man got me. Thank you, Orkin Man.”

Replied Maksudian, while sliding away in the foamy floor of the Blue Jays clubhouse: “Hey, man, we love you.”

At some point during the celebration, Maksudian promised that he would get a Blue Jays tattoo on his butt. And after the team won it all, a championship to which he objectively contributed nothing on the field, he announced to the 50,000 fans assembled at the SkyDome, a finger pointed triumphantly in the air: “I got it. I still gotta get one more for the World Series.”

***

The Twins claimed Maksudian off waivers that offseason, and he entered spring training as one of three potential backup catchers for the team. As one report put it, “Lenny Webster is the one with a full year of major league experience. Derek Parks is the former 1986 first-round, free agent draft choice. Mike Maksudian is the newcomer who eats bugs.” Maksudian clarified to the Minnesota media that the bug-eating, though now his primary claim to fame, was merely part of his competitive strategy: “I think in order to be the best at whatever you do, you have to be a little different.”

He sustained a stress fracture in his arm during the spring, and did not appear in the Twins’ lineup until mid-June. In 17 plate appearances that month, he recorded two hits and four walks, and he did not play for the Twins again after that. While in Triple-A with the Portland Beavers, though, he continued to build his legend. When Toronto media came to talk to him there, where he was among the league’s top hitters despite missing time to injury, he was asked to recount the story of the locust. This time, the amount of the cash prize ballooned from $800 to $1,200, and the list of things he had consumed only grew: from only insects before, it now supposedly included beetles, worms, aquarium fish, and small lizards. He shaved his entire body, head included, in an ostensible attempt to break out of a slump, and claimed it had worked.

All of this sounds very strange, and quite possibly more a distraction for a baseball team than anything else. But according to the Beavers’ assistant coach Paul Kirsch, Maksudian’s was a necessary presence, even beyond his .347 batting average: “We’re together every day for five months, and life can get monotonous pretty quickly. Mike is one of the guys that keeps everybody loose. You need players like him in the clubhouse and on the field.” I could find no such accolades from members of the 1994 Cubs, for whom Maksudian played 36 games before the strike cut their season short. Only the Padres were worse in the National League that season. Winning can make having fun a lot easier.

***

Being young can make having fun a lot easier, too. After seven years of fairly consistent production, Maksudian’s body began to break down. Over the 1994-1995 offseason, he had surgery on his rotator cuff, and through the first month of the 1995 season, he had one of the worst slumps of his career, batting under .150 with the A’s affiliate Edmonton Trappers. Gone were the tales of escalating shenanigans, the questions about bug-eating, and the increasingly exaggerated answers. Instead, the questions centered around a future that looked more uncertain by the day. At 28, was Maksudian reaching the end of his baseball career?

“It’s been a battle since the day I walked back on the field,” he admitted to reporters, who noted his frustration with himself. “I keep trying to find that same old swing, but I’ve had to make some changes. … Every day you come out and you think to yourself, ‘This is the day I come out of it.’ And every day you don’t, you leave the yard upset with yourself. This is the worst I’ve ever hit in my life, but I’ll get past it.”

I’ll get past it. That was the fundamental message of everything he said, even when it was an acknowledgement of the extraordinary difficulty he’d been having: confidence in his ability. There are players whose frustration becomes more evident—you can sense the burden their failures place on them, and even false confidence is unconvincing. Maksudian’s confidence seemed genuine. Because despite all of the tomfoolery that had gained him fame, he was still a baseball player. This was his job, the passion he kept returning to despite the setbacks and demotions. “I’ll get it back,” he said, of that same old swing. “Slowly but surely, it’s coming back. When it does, I think my natural ability will take over. I’ll be fine.”

***

He was not fine, not really. While Maksudian managed to bring his batting average up to a more respectable level as the summer went on, the power that had characterized his years of success in the upper minors never really recovered from the torn labrum. From slugging .551 in Triple-A the year before, the best season of his career, he slugged only .392 that season with the Trappers. It was a precipitous decline, indicative that something essential had been lost.

What wasn’t lost, though, was his identity as Mad Mak. Even as a 28-year-old veteran, even having the most painful season of his career, he was still the clubhouse prankster, the one keeping it loose. He convinced a teammate that he had been traded to the visiting team, to the point where said teammate went into the visitors’ clubhouse to introduce himself. He also took a pie to the face during a live TV interview.

He even became the face of the PCL’s then-controversial reputation as the “friendship league,” breaking fraternization taboos to hug a former teammate while both were in uniform. Rick Dempsey, manager of the PCL’s Albuquerque Dukes, thought it was a sign of an uncompetitive softness threatening the game: “I’d like to see more rivalry in the game, more on-field hatred,” he said. Newspaper columnists opined about the days of Ty Cobb and his spikes. Maksudian kept pulling pranks and giving hugs. He kept on being himself.

***

On June 30, Maksudian finally hit his first home run of the season. It came in the midst of a small four-game hitting streak—a triple and a couple of doubles to go along with the homer—that signaled at least a little bit of hope for a return to form. The next day, he was gone. Not just gone from the field, gone from the lineup. He was nowhere to be found in the dugout. Another day passed. He was still gone.

Baffled by the absence of a beloved player, a local reporter deemed him missing, and set up a hotline for people to call in tips regarding his whereabouts. On July 3, the Trappers finally issued an update on his status: he was on the disabled list with a “rib contusion.” There was no word on how this rib contusion was incurred, and no word on how long Maksudian would be out. When he returned to address the media on July 12, he sported a knife wound in his chest. The “rib contusion” had been a euphemism for “stabbing.” A few inches different, and Maksudian would never have played baseball again. The blade would have hit his aorta, and he would have died.

The night of that home run, Maksudian had gone out to a local club to celebrate with his teammate and roommate, Jim Bowie, when Bowie, a black man, began to receive racially-motivated harassment from some club regulars. Maksudian defended his friend; the bouncer kicked both the harassers and harassees out into the street, where the fight continued. Someone spat on Maksudian. Punches were thrown. And then, just like that, Maksudian’s life could have ended. “I finally hit one after the season I’ve been through and this happens,” said Maksudian, “I was just starting to get my swing back, too.”

Less than two weeks later, he was back in the lineup for the Trappers, cracking jokes about how the ladies might love his new chest feature. He could easily have been dead; instead, he was okay. Better than okay. He went on a hot streak.

When the 1995 season ended, so did his career.

***

“Does anyone remember Mike Maksudian?” a YouTube commenter asks on a video of the Blue Jays’ World Series celebration. “His biggest claim to fame was eating insects that may not mean much but he was only professional ball player for only 3 years 92-94 has a career average 220.”

That about sums up Maksudian’s legacy in 2018. I don’t think many people remember Mike Maksudian in their baseball reminisces. He played very little for a great team, and then very little for two not-great teams. Most people don’t remember career Quad-A players. There’s not really any reason to. We are drawn to stories in baseball that are important, stories that mean something. Maksudian’s numbers, at least in the big leagues, never amounted to much of anything. Comic relief usually doesn’t go down in sports history as important, not if it’s unaccompanied by a remarkable performance. It makes sense.

But I’m glad he had the career he did. In 2018, when so many things in baseball and outside of it can feel so dire, Mike Maksudian is a reminder of the fundamental goofiness of this sport. Baseball is a big deal, and it’s not a big deal at all; it is very serious, and it is also very silly, and all of this can sometimes be easy to forget. Sometimes you need to remember to laugh at the dumb shit, to try to lighten the burdens others carry as well.

Mike Maksudian’s career moved forward, regressed, and stagnated; he knew failure and injury, and he almost died. He also ate bugs, hugged his friends, dumped a beer on Dave Winfield’s head, and got ass tattoos. At the end of it all, he was fine.

References

Brownlee, Robin. “Mighty Mak back swinging.” Edmonton Journal, July 2, 1995.

Brownlee, Robin. “Stabbing no laughing matter: Maksudian lucky injury not more severe.” July 13, 1995.

Brownlee, Robin. “Trying to find ‘that same old swing’; Trappers catcher Mike Maksudian battles back after surgery.” Edmonton Journal, May 30, 1995.

Byers, Jim. “Jays bug rookie catcher the day after locust.” Toronto Star, September 10, 1992.

Eisenbath, Mike. “Two Dreams Go On, Even After Draft Quietly Passes.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 23, 1992.

“Ex-Jay sticks to diet and will take a dare: Maksudian endures bug-eating habits.” Globe and Mail (Toronto), June 30, 1993.

Konotopetz, Gyle. “Fraternizing sparks heated debate.” Calgary Herald, June 21, 1995.

Konotopetz, Gyle. “Maksudian still keeps all around him loose.” Calgary Herald, June 11, 1995.

Milton, Steve. “Mike comes out of the closet.” Hamilton Spectator, September 1, 1992.

Perkins, Dave. “Winfield’s birthday bash truly a winning affair.” Toronto Star, October 4, 1992.

Rusnell, Charles. “Trappers’ catcher knifed in fight; Home-run celebration ends in brawl outside nightclub; Bar owners and bouncers believe violence among customers is down.” Edmonton Journal

Ryan, Allen. “Maksudian lines up with Jays.” Toronto Star, September 1, 1992.

Souhan, Jim. “A full plate: Three catchers competing for one opening as Twins backup.” Star-Tribune (Minneapolis-St. Paul), February 28, 1994.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Mike Maksudian has been an entrepreneur since his professional baseball career culminated in 1996. During his 9 year professional baseball career Maksudian played in the Minor leagues with the White Sox, Mets, and A's and spent time in the Major Leagues with the Twins, Cubs and Toronto Blue Jays. Maksudian was called up to the Major Leagues in 1992 when the Blue Jays won the World Series.

After baseball Maksudian spread his entrepreneurial wings and started an internet based scouting and recruiting company in 1996; owned and operated an insurance brokerage through the late 90's and early 2000s; invested in, purchased/sold, and lent on real estate transactions in the mid 2000s; and currently operates as an independent Sr.Technology Consultant selling enterprise class IT hardware, software, support and services.