I think many people, including myself, learned to love baseball because of its dependability. It’s not a new or original idea that, in a world that regularly reminds us of our insignificance and helplessness, we find comfort and safety in what we perceive to be bigger than ourselves. I imagine divinity, from Jesus to Zeus, sprang from this feeling of helplessness. There have to be things we can count on.

For a long time, we could easily trick ourselves into thinking that our city’s baseball players fell into this category. Sure they could be traded, or retire, or wash out, or suffer an injury working their offseason job to pay the bills. For most, though, it was one team, one city, win or lose, as long as they played. The people of St. Louis experienced decades — WWII, the Korean War, the rise of television, Martin Luther King proselytizing his dream at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial — all while spending their summers watching Stan Musial in the outfield. The great ones became a living statue, a doubles-slashing ornament of civic pride.

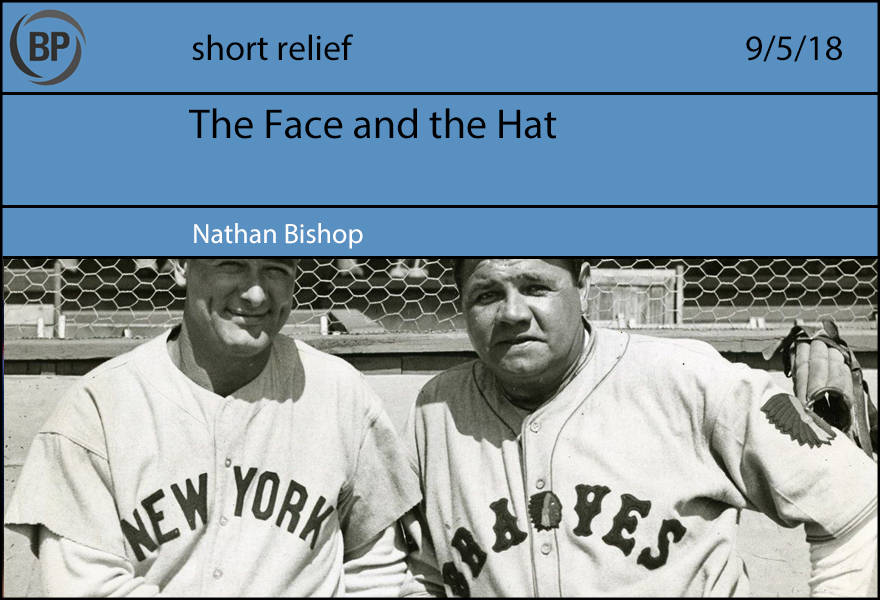

It’s the face and the hat, I think. The combination of the two, looking right at the camera, is a 50/50 split between player and team, individual and organization, that is unique to baseball. Each team seemingly has a player (or many if you’re a pod-living, soulless Yankee fan) its fans close their eyes and can see, maybe with a bat resting on shoulder, or leaned over as though trying to read the catcher’s sign. Edgar Martinez, Bob Feller, Cal Ripken, Jr., Roberto Clemente, and on. The face and the hat, over the years together, become a single entity to an entire region. They get filed into the same parts of our brain as the lake we fished as a kid, or the way our grandfather laughed when he told a joke. Fat, happy, fuzzy, oversimplified, baseball.

It’s not real, of course, and invariably the idea of player as institution is lost. Sometimes it’s retirement, speeches and statues. Most often these days it’s just a tweet:

It’s just a different hat, but it throws off the entire face. Deep down we know it isn’t real, but just as deep we knew we needed to let ourselves believe it. We’re stuck trying to find a new face now, one that fits the hat just right. It gets harder every time.

Home runs: ugh, gross. I’ll say what we’re all thinking: Where do the balls go? Do they ever come back? As Ryan Howard officially retired from baseball this week, plenty of people will come forward with their favorite memories of what he did best: Hit home runs. But I’m here to tell you that for every soaring, majestic moonshot, there was an awful dinger to even the count. Or actually, just five of them.

Obnoxious. This balls lands way too far away. And it was his third grand slam of the season. Got any other tricks in the bag, Ryan? Just monstrous offense and a future as a children’s author? [Dismissive snorting noise]. I think I speak for all of Philadelphia-area sports talk radio when I say, “Do something else, but also don’t stop doing this, and also understand that none of it will ever be enough.”

One home run is a statement: LOOK HOW FAR I CAN HIT THE BALL. Two home runs is confirmation: THIS WAS NO ACCIDENT. I AM CAPABLE OF MASSIVE HUMAN BRUTALITY. Three home runs? The fans are asleep. The other team has tuned out. Why bother pretending to chase a fly ball that has absolutely no chance of staying in the yard? LOOK, you’re saying. LOOK, I’M STILL DOING IT. I’M STILL HOMERING THE BASEBALL AWAY. The fans may sound like they’re roaring in appreciation of his third home run of the day, perhaps, some would say, even more raucously than the first, but listen closely: NO, they’re screaming. STOP. YOUR POWER ALARMS AND FRIGHTENS US. WHO ARE WE TO WITNESS SUCH STRENGTH. WHO ARE WE TO COMPREHEND SUCH MIGHT. WHAT REASON DO YOU HAVE NOT TO UNLEASH SUCH HORRIFYING MADNESS UPON US, THE FANS, FOR DISPLEASING YOU? NAY, RYAN; GO LIVE IN THE DEEP WOODS OF THE WISSAHICKON, BECOMING BEARDED AND GRIZZLED AND LEAVE US IN PEACE. That’s what they’re saying.

Baseball is a sport infected with jealousy. “Not my team!” says you, pointing out that the fun, young team that lives in your city. But the truth is, those smiling, clapping, screaming young men are coursing with rage at each other. Those customized celebrations after home runs? Walk-off dog piles at home plate? All the while, they’re imagining elaborate, soap opera death fantasies. Why do you think their first instinct to celebrate a walk-off is to attack the person who won the game? The World Series-champion 2008 Phillies weren’t immune to this disease. Howard just couldn’t let Chase Utley have the spotlight, could he? Not even in the World Series. People watching the postseason don’t want to have to stand up and acknowledge two home runs in a row. They’ve exhausted themselves, and likely don’t have the energy to stand up again. But Howard wasn’t afraid of inflicting such hardship upon his own fans. Needless. And when’s the last time you heard a Phillies fan celebrate Chase Utley? That’s right, he’s been completely forgotten.

This three-run shot brought Howard to 1,000 career RBI in only 1,230 games, the fewest amount of games needed to reach such a landmark. Which begs the question: Why was he in such a hurry? Baseball is a sport meant to be played with no urgency. It is the top sport viewed by people who have accidentally consumed too much cough medicine and cats currently asleep in a sunbeam. If you’re just going to crush dong after dong at a pace the sport has never seen, then you clearly don’t understand the philosophy at the center of our pastime. We’re trying to relax here, not compare our horrifying lack of productivity to an athlete reach the upper echelons of their sport.

Honestly, what was he even thinking here? The 2006 Nationals were still playing if RFK Stadium at the time, which is why it looks like the ball lands in the back rows of a haunted warehouse. Using their poor, pathetic roster written on wet paper with a mostly dried-out marker as a punching bag was just straight up cruel. And not only that, but flaunting his strength with the 49th home run of his season at a time when everyone on the home team was wishing they were anywhere else or dead was just a lack of basic human decency. On top of all of that, the home run allowed Howard to surpass Mike Schmidt for the Phillies single-season franchise record. Mike Schmidt is not a milestone to be passed. Some poor Philadelphia souls believe he is actually 10 feet tall and made of bronze and lives just outside the third base gate of Citizens Bank Park. Philadelphia needs Mike Schmidt to be everlasting, to be absolute, to be impenetrable — indestructible to self-made media disasters, to turning the #MeToo movement into a golf course punchline, and to Ryan Howard breaking his home run record. This home run was a sign that Howard had no respect for the past or Philadelphians’ desire to live in it.

The baby monitor is two inches by three inches, its screen dim and periwinkle in the darkened bedroom. It is not an expensive monitor, so as the figure on the screen kicks and thrashes, the image stutters, like a demonic, sideways Sportflics card. The only light it picks up from the room are the pupils of my son’s very open eyes, white pinpricks on an otherwise shapeless face. Above the screen are a series of lights, progressing from green to red, displaying the volume level of the toddler’s bedroom. It is loud. I can tell this because of the red lights, and also because his bedroom is next to mine, and he is screaming my name in perpetuity. Between sobs, the device sighs like a disappointed ocean.

It goes like this for an hour, punctuated by the occasional escape attempt, a demand for a stuffed animal housed in the small of his back, ten-second bursts of silence that cement the torture. I lie on my stomach and wait. Sometimes he is still, but you can’t trust your eyes; usually it’s just the monitor losing the connection to the camera. We have been sleep training the boy for three weeks, to little progress; he sleeps only because has no more energy to cry.

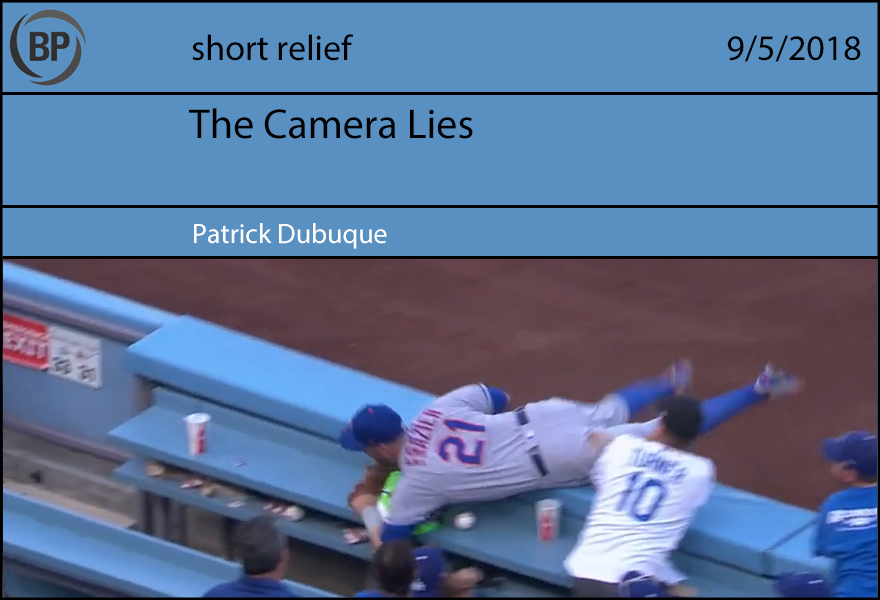

Finally I stumble downstairs and flick on the computer to start my second job. Open up the google docs, check Twitter to see if the Seattle Storm won, and get greeted by this:

Well, now: Todd Frazier got caught outright cheating, I think to myself. That’s pretty rare. Probably a story in that, not that I have the energy to write it. I should watch the video.

I watch the video again. And again.

I’m tired, and I can still hear my son even though I’m pretty sure I left the monitor upstairs in the empty bedroom like an idiot. I’m not in a good place. But I’m pretty sure that Todd Frazier did, in fact, catch the ball.

It’s late; no one is on gchat. I go back to my Twitter feed. Naturally, it’s out of sequence, helpfully arranging my timeline in a way that I have no sense of time. No one seems to be reacting to the catch, or the lack of catch. I’m getting a little creeped out now. I search Todd Frazier. People are retweeting the Deadspin piece, or Cut4. The catch is yesterday, I learn from my friend Chris. The reports of cheating hit forty minutes ago. Everyone is wrong. Everyone is wrong but me. The ball that is seen rolling out from under Frazier along the railing pops out of a bag that he lands on; it is emerging while the real ball is still (at that point) in his glove. The ball that the fan can be seen holding later is the rubber ball. I watch the video again. It is still true. I’m sure of it, which means I’m not sure of anything.

Upstairs the boy is howling; I can’t hear him, but I can hear him. “Daddy,” he howls alone into the periwinkle blackness. My arms itch from the restless nights. I watch the video again. Everyone wants Todd Frazier to have cheated, and I can’t figure out why. Everyone is wrong.

I’m wrong, and I can’t figure out why. I can’t trust my eyes.

[Editor’s note: it is now Wednesday morning. I am back under the comforting fluorescent sunlight of my office. I’ve had five solid hours of sleep. And Todd Frazier still caught the ball.]

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now