It was a letdown, when this year’s Women’s Baseball World Cup ended, to go back to watching men’s.

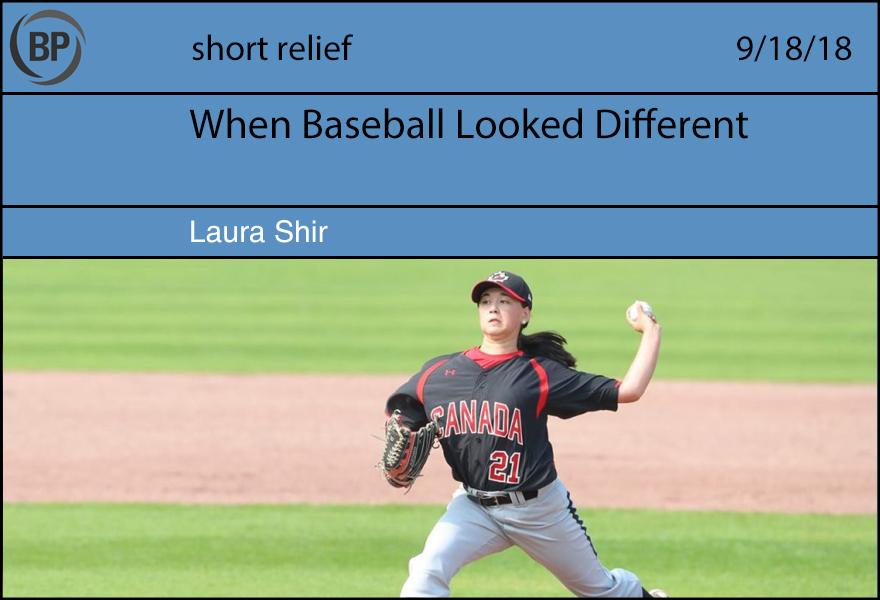

Much has been written about the hard baseball details of the women’s tournament: the match-ups, the spin rates, the turf, the rain, the sharpness of the double plays and the joy of the home runs. The athletes deserve to have these details covered by the national sports media; they deserve attention and accolades, sponsorships and scholarships. But what made an unexpected impression on me… was what the players looked like.

Appearance is a fraught topic for female athletes. Too often, women in all professions, but particularly those in which their bodies are the focus of their work, are reduced solely to their beauty rather than their ability. The egalitarian approach would be to ignore appearance, lest we distract from the real point: skills, mastery, the opportunities that generations of female athletes have fought so hard to access. But in this case, the way the athletes looked added to the emotional impact the tournament had on me.

They looked like women, of course. But what does that mean? As a queer woman, what that means to me changes every day. I’m cisgender, which means when I was born, a doctor looked at me and said “it’s a girl,” and 24 years later I still think that doctor was right. I am a woman. But the way I wear my gender, and the way my gender wears me, is a process I struggle with.

The women ballplayers I had seen before had never particularly spoken to that side of me. From its inception during World War II, the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League enforced strict femininity. The league forced the players to play in dresses and take etiquette classes to weed out “masculine” women, particularly lesbians. (And, of course, it was only for white women—a fact often glossed over when the league is memorialized today.) When I first watched women’s college softball, I was amused to see the colorful hair ribbons worn by so many of the players. But then I learned how even those brightly-colored bits of fabric have been weaponized. Certain straight women softball players, tired of homophobic stereotypes and more than a little bit homophobic themselves, use the bows as symbols to demonstrate that they’re still feminine, they’re not like that. Not like me.

So imagine my surprise when I turned on the Women’s Baseball World Cup, and right there on Team USA was every way I had ever considered being a woman. On Kelsie Whitmore (RHP/OF), I saw the hair I dreamed of having in high school, waist-length and mermaid-like, floating loose as she coiled her wiry strength to let a pitch fly. Malaika Underwood (1B), compact and serious, embodied the androgyny I wished for sometimes in college, as I tried and failed to be taken seriously in the queer communities there. Brittany Gomez (OF) was wearing the kind of flawless eye makeup I’ve never mastered, visible in the close-ups during her at bats. And Megan Baltzell—well, she became the only DH I’ll ever believe in, and her raw physical power made me feel like I could conquer the world.

I don’t know how any of these women define their genders or their sexualities. The way they made me feel may have no bearing on how they feel about themselves. But they gave me a gift, whether they know it or not. They taught me something I’ll never forget: There are a million ways to be a woman. There are a million ways to be a ballplayer. There are infinite ways to be both.

My cat Henry has, over the past year, become afflicted with some kind of neurological disease that a string of veterinarians can’t solve. About once a month—sometimes more, sometimes less, usually in the summer month—she has what I’ve come to refer to as “episodes,” which are something akin to a cross between a grand mal seizure and an exorcism.

It always starts the same: he cries, a piteous mewl, and runs around in desperation seeking a hiding place. The attacks give him severe vertigo, though, and he can’t control the direction of his tiny furry body, which leaves him vulnerable to fall down some stairs or crash into the wall. Over many, many months of practice I’ve developed a protocol for when I hear that first meow: I wrap Henry in a towel and crouch over him, pinning him in place and holding his head while his eyes spin wildly and he cries, a low, guttural “what is happening to me?” sound. After about 10 to 20 minutes, he whimpers to be let up and I help him limp into a cardboard box turned on its side, lined with a blanket and covered with another blanket, that I keep around the house for expressly this purpose.

The name the vets gave it is “feline vestibular syndrome.” No, they can’t do anything. I could take him to a neurological specialist in another city if I want more answers, but they can’t guarantee anything. He has some anti-nausea pills I can give him that help him sleep, if he doesn’t throw them up first. The attack lasts for the better part of the day; he stays in his dark box in a dark room, and I stay nearby and wait for him to emerge and ask for food.

Nothing is enjoyable about this process, clearly, but the worst part of all of it is the lack of control both of us experience in the situation. Other than a panicked cry, Henry can’t communicate what’s about to happen. I can’t do anything for him, other than the most basic palliative measures. I can’t afford to take him to a neurological specialist halfway across the state, but even if I could, there’s no guarantee it could help anything. It’s a problem money can’t solve.

Over the past few months, I’ve watched the Mariners fall out of contention for a playoff spot in a similarly slow and agonizing manner, and with the same feeling of powerlessness. There’s nothing I can do but spectate. This week, I read about the Angels potentially extending a lifetime contract to Mike Trout, and Reader, I shuddered. Mike Trout has watched his baseball team wilt around him on the path to the World Series every year except one. He has put up legendary, all-time-great numbers, and it hasn’t mattered at all in helping his team ascend to a World Series berth. This year, after largely being proclaimed winners of the off-season, the team will finish in third place in the division, double-digits out of a Wild Card appearance. It’s a quirk so twisty it’s fabulist, like at Trout’s birth a fairy godmother came down and blessed him with the ability to be the greatest player of his generation, but then didn’t check the fine print on the contract that wizard in the woods wrote up. It’s a reminder that all of us, in the larger sense, are subject to the whims of a matrix much bigger than us. It’s a reminder that sometimes money just isn’t enough.

It’s no secret that US Presidents have a deep relationship with professional baseball, dating back to the Cincinnati Red Stockings’ visit to the White House at the behest of President Grant in 1869. From there, professional baseball champions have routinely visited the president’s residence, and vice versa. Indeed, it is far more unusual and somewhat alarming when presidents are incapable of or unwilling to partake in the national pastime.

In the past 150 years, the connection between US presidents and Major League Baseball has become such a profound microcosm of American identity that one can’t help but feel sad for the presidents who had the misfortune of existing prior to professional baseball. There is little doubt, though, that each one, were he alive today, would proudly embrace a team, hometown or otherwise. Since none were cryogenically frozen, we might never be able to concretely assert just which team would capture their rooting interests, but that doesn’t mean we can’t speculate.

Over the next number of weeks (until I complete the project or become bored of it), I’ll provide a list of potential teams for each president, ranked according to the following criteria, partially based on the 2017 C-SPAN Presidential Rankings: crisis management, character and integrity, performance within context of the times, mascot fittingness, and location.

Since he was the first president and therefore the one who brought the office to life, let’s start with George Washington.

Crisis Management: 3.0

Moral Authority: 4.0

Performance within Context: 9.5

Mascot Fittingness: 2.0

Location: 7.0

Total: 25.5/50

George Washington is frequently titled the greatest president in US history, and the Yankees are the greatest team in major league history, this would seem like an obvious choice. However, the franchise loses major points for its crisis management skills; as crises are few and far between, each minor inconvenience is exaggerated by its free and independent press.

Crisis Management: 8.0

Moral Authority: 5.0

Performance within Context: 5.0

Mascot Fittingness: 5.0

Location: 6.0

Total: 29.0/50

Without the Cincinnati Reds, professional baseball might not exist; without George Washington, the office of the president might not exist. The original Reds team was kicked out of the NL for playing baseball and serving beer on Sundays, hardly dignified behavior for a US president, but George Washington firmly believed in religious freedom and loved his brown liquors. The Reds have been at the forefront of much of professional baseball and have thus survived many crises, including undergoing a temporary name change. It’s a resilient franchise that ultimately falls short due to its relative lack of professional success.

Crisis Management: 7.0

Moral Authority: 6.0

Performance within Context: 6.0

Mascot Fittingness: 9.0

Location: 9.5

Total: 37.5/50

The Baltimore Orioles are the youngest of these three teams, having existed in various forms dating to 1901 with its modern incarnation since 1954. In that time, the franchise has weathered the storm, from murky origins to many losing seasons, peppering in a fair bit of success along the way. It is not Baltimore’s qualities as a professional team, though, that makes it perfect for Washington. Rather, it is the first professional team close to his home of Virginia. Plus, the man just really loved birds.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now