On April 17, 2015, Kris Bryant made his MLB debut for the Cubs. Bryant had a rough game that day, going 0-for-4 with three strikeouts, but over the next few months, he made up for it. Bryant made the All-Star team, won Rookie of the Year, got a few down-ballot MVP votes, and finished with a .275/.369/.488 line for the year. And 171 days of service time on the roster.

A full year on a major-league roster consists of 172 days, which means that at the end of the 2020 season, Bryant will have five years and 171 days of MLB service, leaving him one day short of the six years that he would need to file for free agency. He’ll still be eligible for arbitration, and given that he’ll probably receive a paycheck with a lot of zeroes on it that year, it’s hard to feel too bad for him, but he’ll have to play out the 2021 season before he’s eligible for the free market.

It’s something of an open secret as to why this happened. Prior to April 17, 2015, the Cubs started Mike Olt (he hit .191/.255/.319 and hasn’t been back in the majors since), Tommy La Stella (.269/.324/.403), Jonathan Herrera (.230/.242/.333), and Arismendy Alcántara (.077/.226/.077) at third base. The Cubs weren’t exactly flush with talent at the hot corner. But officially, Bryant just needed a little more seasoning at Triple-A Iowa, where the year before he hit .295/.418/.619.

Now that we’ve reached September, we see a new round of it happening again. Out-of-contention teams with blue chip prospects whose minor-league seasons have finished and who would probably benefit from a taste (however brief) of big-league life are being told instead to go home. Fans of those teams—who obviously don’t have a playoff run to look forward to, or potentially even a win if they show up at the ballpark—might come out to see the next big superstar, but … well, it would start his service time clock.

From a team’s perspective, it makes perfect sense. Free agency happens after six years of service. Teams have full control of when that clock begins. I know many people see this as an ethical issue, but if you’re waiting for teams to refrain from doing something that is within the rules and that means protecting what could be a valuable resource, then you will be waiting for a very long time.

But maybe there’s a way around it. Or at least there’s a solution that substitutes in a problem that people find less bothersome.

Warning! Gory Mathematical Details Ahead!

The solution I’m proposing isn’t novel, with Mike Axisa (here) and Jonah Keri (here) among those who’ve already written on the subject. Today, I’d like to show why it would actually work. I propose that MLB should have age-based—rather than service-time based—free agency. The end of a player’s age-28 season makes the most sense, and we’ll get to why that is in a moment. But the system would still preserve the hybrid “team control” for the early years of a player’s career, mixed with free agency for his later years that exists now.

Players who would be 29 by April 1 of the following year could file for free agency after the World Series. In this way, the mechanism for determining a player’s free agency is no longer controlled by his team, but by the calendar. But to get there, this would have to be collectively bargained, and in any bargain, both sides need to walk away from the table feeling either that they got something of value or at least that they’re no worse off than they were before.

You’re going to have to sell it to the owners.

Let’s look at the marginal effects of such a shift. This scenario would give us four groups of players.

| Years of service time? | How old are you? | Result compared to current system |

| Fewer than 6 | 28 or younger | “Team controlled” either way |

| Fewer than 6 | 29 or older | Free agency earlier than old system |

| 6 or more | 28 or younger | Free agency later than old system |

| 6 or more | 29 or older | Free agent either way |

Under the current system, if a player comes up at 20 and sticks in the majors, he’s a free agent by 26. In an age-defined system, teams would have his services for two extra years. Indeed, it doesn’t matter when they bring him up because the clock will run out on a date that was specified decades earlier, so they can bring him up whenever it makes sense to do so from a player developmental point of view. We’ve solved the Vladimir Guerrero Jr. and Eloy Jimenez problem! Not so fast. What of the player who debuted at 25? He’s not a blue chipper, but he provides enough value to stick around for a few years, and he’s set free into the market after only four years of team control. Teams would be losing out on those guys. But how much would the trade-off be?

Using WARP, we can look at exactly how much value teams would be gaining and losing in each group, depending on where we set the age. I used data from 2000-2018 (through last Friday) and generated the average league-wide value (per year) produced by each group. Value “gained” represents teams being able to hold on to young debutantes longer. Value “lost” represents the players teams would have to set free earlier than the current system.

| Age cutoff | Batter value “lost” | Batter value “gained” | Pitcher value “lost” | Pitcher value “gained” | Net value |

| 26 | 119.92 | 13.68 | 81.43 | 6.49 | -181.18 |

| 27 | 72.57 | 29.26 | 49.84 | 15.41 | -77.74 |

| 28 | 39.26 | 56.58 | 28.49 | 33.92 | +22.75 |

| 29 | 18.19 | 94.24 | 15.90 | 52.52 | +112.67 |

| 30 | 8.06 | 136.91 | 9.54 | 71.69 | +191.00 |

With a cutoff at 28, teams would be able to hold on to an average of 90.5 WARP worth of production overall (about 3.0 per team), mostly in the form of having a few extra years of “team control” with players who debuted early. These tend to be higher-value players. They individually averaged 2.0 WARP among the batters and 1.5 WARP among the pitchers in this group, so they’re probably the guys who are a little more marketable. On the flip side, teams would lose out on 67.75 WARP that would have been under team control, but will now (presumably) be priced at free agent levels. The players who tend to be in this group are late-bloomer, lower-value guys, though there are more of them. The batters averaged 1.17 WARP and the pitchers 0.38 WARP.

With the cutoff set at 28, players would enter free agency for their age-29 season, still in their prime years. Teams would no longer have any incentive to sit on good, young players or manipulate service clocks (the entire point of the exercise). They would realize value that they are currently denying themselves by bringing up the young players, and while that’s not a competitive advantage if everyone can do it, it at least makes the game better.

It all seems about right until we realize there’s a word we haven’t said yet: arbitration. It’s possible that if a new Collective Bargaining Agreement were to move toward an age-based free agency marker, they’d blow up the entire system of arbitration as it currently exists. But the path of least resistance is going to be using a modified version of the “team controlled” salary structure, presumably one that’s also tied to age, rather than service time.

For a moment, assume that in the new system, players will be eligible for arbitration to set their salary for their age-26, age-27, and age-28 seasons, and that the arbitration process will work more or less as it previously has. There’s a reason that a player’s “arb years” are considered to be “team friendly” years, as it’s widely understood that the arbitration wage scale under-pays players relative to what they would get on the open market. Estimates settle around players making 40 percent of their fair market value in their first year of arbitration, then 60 percent and 80 percent in years two and three. (After that, they are free agents.) Right now, arbitration, like free agency, is tied to service time, with players eligible after completing three years (or being eligible through the “super-two” provision).

Two issues would need to be dealt with in this new setup. One is logistical: what happens when a 26-year-old hasn’t yet made his MLB debut? Right now, that player makes the league minimum when he’s called up for the first time, and if he sticks around, he eventually gets to arbitration after three years. In fact, if he debuts at 35, it’s the same story. But if we’re bench-marking things by age, what shall we do with our 26-year-old debutante? In fact, what do we do if he gets called up to the big leagues on June 11 to provide bullpen depth for a couple of days? Should he have to stop off at the arbiter’s office before reporting?

There would have to be some sort of provision for these guys. The way I see it, there are three options:

- Any player about to enter their age-26 season who has not debuted is declared a free agent and may sign or re-sign with any team. That might include signing a minor-league contract with a clause noting what his salary would be if he’s promoted. It’s likely that a lot of those numbers would be “the MLB minimum,” but that would be a matter of negotiation between free parties.

- Teams must either decide to offer arbitration to these players or non-tender them, the same way that they do with any arb-eligible player now. Non-tendering would make them free agents. Arbitration might result in a contract similar to the above, with the arbitrated salary only taking effect if the player actually makes the majors.

- The new CBA could simply state that a player making his MLB debut in his age-26 (or 27 or 28) season is eligible only for the minimum salary. This would be on par with current conditions. In the following year, he could be eligible for arbitration (or free agency) with his age cohort.

The arbitration process would go through a small period of adjustment. Right now, the process is heavily dependent on comparison cases to judge what a player might “deserve,” but the nice thing about the current system is that all players applying for their arb-1 salary are being judged on three (or so) years of performance, so there’s a broad base for comparison. The system hasn’t really seen a case with a player having only a minor-league record, so there would be some initial feeling out. (There would also be a similar process for players who debut at 25, and thus go into their first arbitration hearing with only one year of a record to examine.) In reality, if a player hasn’t poked his head into the majors by 26, he’s likely to be more of a fringe guy. Players who debuted at 26 or later provided an average of 0.62 WARP for hitters and 0.24 WARP for pitchers in that debut year. Those kinds of comps will probably get them the MLB minimum.

The first option might encourage bad behavior, such as teams promoting marginal 25-year-olds whom they want to “keep around” at the end of the season and sticking them into one game. The third option might result in bad behavior in the form of teams not calling up marginal 25-year-olds in September so as to save a few hundred thousand bucks in a potential arbitration case. (I doubt somehow anyone will write an article about how the game would be saved if only they could see some garbage time at-bats for an out-of-contention team.) I can’t say that I have a proper recommendation among the three, but all three options appear logically feasible and could be negotiated out, and they probably practically all land in the same place with these marginal cases making near the league minimum, as they do now.

But then there’s the Ronald Acuna problem. Acuna made his debut for the Braves in late April and has put up amazing numbers at age 20. Acuna was the consensus no. 1 prospect in all of baseball before the season started, so it wasn’t like this was a surprise. Presumably he’ll be a very special player for the next decade or so. Under the current system, Acuna (thanks to his—ahem—late-April call-up) will play his age-20 through age-26 seasons under “team control” and then will be a free agent going into his age-27 season. The proposed system would make him wait two extra years, and while he would get his three years of arbitration, he’d have to spend two extra years playing at the minimum salary (and bearing the risk of a potential career-ending injury) before he got there.

From the player’s perspective, this new system penalizes being good and young, which is kind of what service time manipulation also does, and that’s what we were trying to avoid. But at least he’s on the field. The new system robs a bit from those guys and instead provides a boost to those who are older when they debut, getting them to free agency faster. In fact, we need to play around with the chart above a little bit. I previously only looked at how much raw value would be gained and lost under the new system, but I didn’t look at how it was priced. Using the same 2000-2018 data, I looked at how much value has been generated, on average, by each group of players—based on when they made their debut and how much service time they’ve accrued—that would be affected by the proposed shift to an age-28 cutoff.

I pegged everything to the idea of dollars-per-WARP in free agency, and for arbitration, used the thumbnail of 40-60-80 percent of that dollars-per-WARP value being assigned to players, compared to what they could have gotten on the free market. I assumed that the league minimum was zero, just for ease of calculations.

For example, a player in row 1, who debuted at 20 and would be eligible for arbitration at 23 under the current system, but would be playing for the minimum under the proposed system. He would be earning 40 percent of his free agent value under the current system, but is playing for “nothing” in the new system. On this class of player, owners save because they would have had to pay more for those wins in the current system, by a factor of 40 percent. So, owners would be getting a 40 percent discount on those wins. Since there were, on average, 5.44 WARP actually generated by this class of player since the turn of the century, owners would have saved on having to pay for 2.17 (5.44 * .40) WARP.

The actual dollar amount saved would be given by Delta times the dollars-per-WARP standard, but for now we’ll simply let the numbers read as discounted wins for ownership.

| Age at debut | Service year | Current system price | Proposed system price | Actual avg. value/year | Delta |

| 19 | 4 (now 22) | 40% of FA | Min | 2.29 | 0.92 |

| 19 | 5 (now 23) | 60% of FA | Min | 2.79 | 1.67 |

| 19 | 6 (now 24) | 80% of FA | Min | 2.34 | 1.87 |

| 19 | 7 (now 25) | 100% of FA | Min | 3.02 | 3.02 |

| 19 | 8 (now 26) | 100% of FA | 40% of FA | 2.47 | 1.48 |

| 19 | 9 (now 27) | 100% of FA | 60% of FA | 1.45 | 0.58 |

| 19 | 10 (now 28) | 100% of FA | 80% of FA | 1.43 | 0.29 |

| 20 | 4 (now 23) | 40% of FA | Min | 5.44 | 2.17 |

| 20 | 5 (now 24) | 60% of FA | Min | 7.84 | 4.70 |

| 20 | 6 (now 25) | 80% of FA | Min | 6.63 | 5.30 |

| 20 | 7 (now 26) | 100% of FA | 40% of FA | 5.38 | 3.23 |

| 20 | 8 (now 27) | 100% of FA | 60% of FA | 7.34 | 2.94 |

| 20 | 9 (now 28) | 100% of FA | 80% of FA | 7.19 | 1.44 |

| 21 | 4 (now 24) | 40% of FA | Min | 15.99 | 6.40 |

| 21 | 5 (now 25) | 60% of FA | Min | 15.57 | 9.34 |

| 21 | 6 (now 26) | 80% of FA | 40% of FA | 16.37 | 6.55 |

| 21 | 7 (now 27) | 100% of FA | 60% of FA | 13.14 | 5.26 |

| 21 | 8 (now 28) | 100% of FA | 80% of FA | 14.54 | 2.91 |

| 22 | 4 (now 25) | 40% of FA | Min | 22.29 | 8.92 |

| 22 | 5 (now 26) | 60% of FA | 40% of FA | 22.40 | 4.48 |

| 22 | 6 (now 27) | 80% of FA | 60% of FA | 22.77 | 4.55 |

| 22 | 7 (now 28) | 100% of FA | 80% of FA | 20.92 | 4.18 |

At a debut age of 23, the old and new system effectively line up. We see that overall, players who debut early lose out to the tune of 82.2 WARP times whatever the dollars-per-win value is. On an individual level, they’ll probably make oodles of money anyway and be set for life, so again, it’s hard to feel too bad for them. However, they are losing out compared to what they have now.

But by a debut age of 24, in the new system, players would actually benefit.

| Age at debut | Service year | Current system price | Proposed system price | Actual avg. value/year | Delta |

| 24 | 3 (now 26) | Min | 40% of FA | 14.06 | 5.62 |

| 24 | 4 (now 27) | 40% of FA | 60% of FA | 14.85 | 2.97 |

| 24 | 5 (now 28) | 60% of FA | 80% of FA | 16.28 | 3.26 |

| 24 | 6 (now 29) | 80% of FA | 100% of FA | 16.60 | 3.32 |

| 25 | 2 (now 26) | Min | 40% of FA | 9.64 | 3.86 |

| 25 | 3 (now 27) | Min | 60% of FA | 12.13 | 7.28 |

| 25 | 4 (now 28) | 40% of FA | 80% of FA | 10.28 | 4.11 |

| 25 | 5 (now 29) | 60% of FA | 100% of FA | 9.25 | 3.70 |

| 25 | 6 (now 30) | 80% of FA | 100% of FA | 8.18 | 1.64 |

| 26 | 1 (now 26) | Min | 40% of FA | 2.64 | 1.06 |

| 26 | 2 (now 27) | Min | 60% of FA | 4.80 | 2.88 |

| 26 | 3 (now 28) | Min | 80% of FA | 3.85 | 3.08 |

| 26 | 4 (now 29) | 40% of FA | 100% of FA | 5.78 | 3.47 |

| 26 | 5 (now 30) | 60% of FA | 100% of FA | 4.02 | 1.61 |

| 26 | 6 (now 31) | 80% of FA | 100% of FA | 3.40 | 0.68 |

| 27 | 1 (now 27) | Min | 60% of FA | 1.54 | 0.92 |

| 27 | 2 (now 28) | Min | 80% of FA | 1.86 | 1.49 |

| 27 | 3 (now 29) | Min | 100% of FA | 1.35 | 1.35 |

| 27 | 4 (now 30) | 40% of FA | 100% of FA | 2.12 | 1.27 |

| 27 | 5 (now 31) | 60% of FA | 100% of FA | 2.55 | 1.02 |

| 27 | 6 (now 32) | 80% of FA | 100% of FA | 1.58 | 0.32 |

| 28 | 1 (now 28) | Min | 80% of FA | 1.31 | 1.05 |

| 28 | 2 (now 29) | Min | 100% of FA | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| 28 | 3 (now 30) | Min | 100% of FA | 1.09 | 1.09 |

| 28 | 4 (now 31) | 40% of FA | 100% of FA | 0.68 | 0.41 |

| 28 | 5 (now 32) | 60% of FA | 100% of FA | 0.43 | 0.17 |

| 28 | 6 (now 33) | 80% of FA | 100% of FA | 0.43 | 0.09 |

| 29+ | 1-3 | Min | 100% of FA | 7.20 | 7.20 |

| 29+ | 4 | 40% of FA | 100% of FA | 1.08 | 0.65 |

| 29+ | 5 | 60% of FA | 100% of FA | 0.92 | 0.37 |

| 29+ | 6 | 80% of FA | 100% of FA | 0.36 | 0.07 |

We see that teams would have to pay a little more for the performances of later debutantes, to the tune of 66.75 “extra” wins. Overall, the players take a bit of a hit giving up more than they get, although to keep the sides in balance, they might ask for a fourth arbitration year to be put at age 25. (Assuming that it pays out about 20 percent of what a player would get in free agency, that would about even out the ledger.) We can at least create a world where the owners and players walk away with roughly the same amount of money.

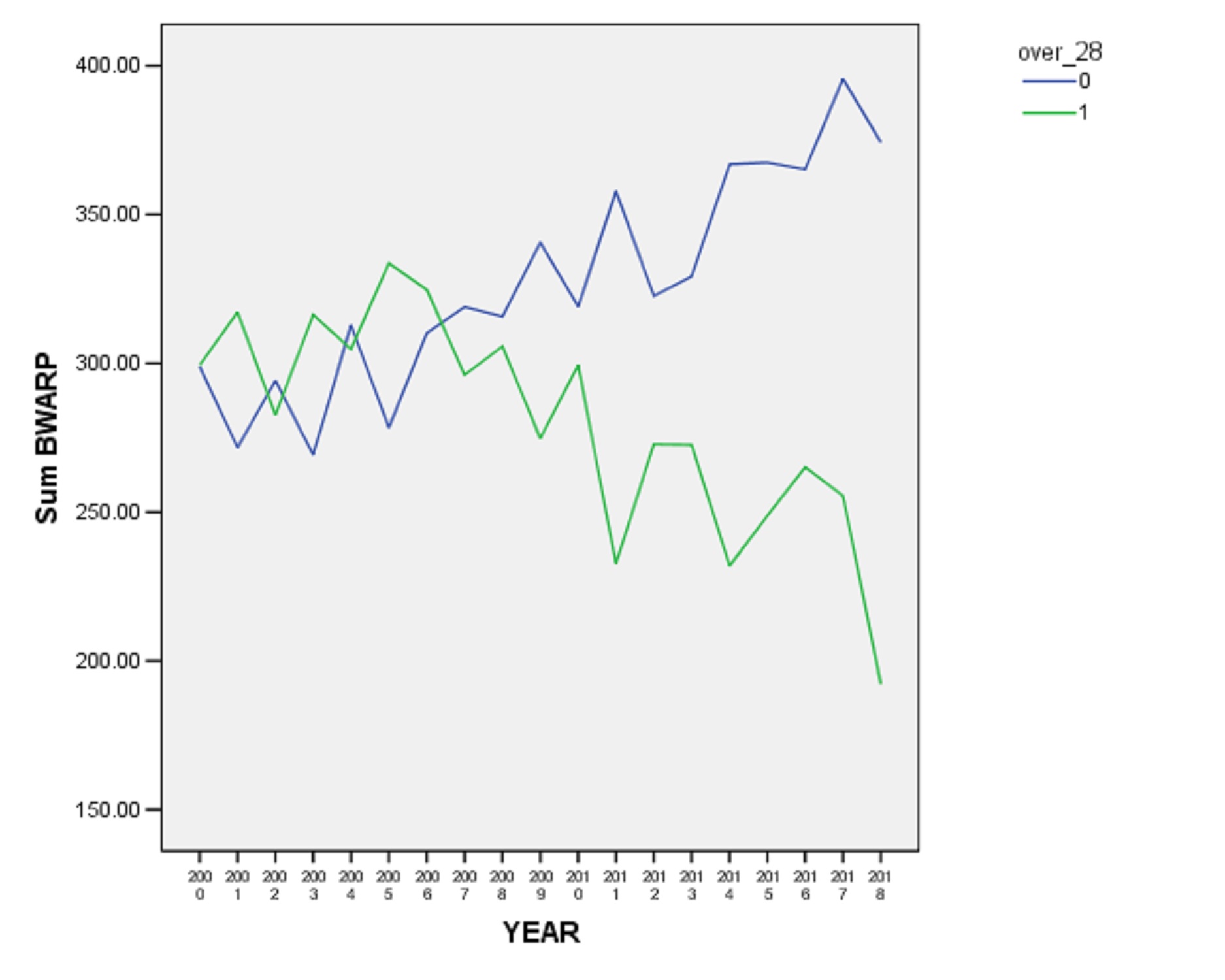

Or can we? There’s a third problem that’s a little more existential. We’ve taken away the incentive for teams to manipulate service time for young players. We’ve done it by making free agency based on age, rather than service time. Will teams simply start shifting away from older players? We don’t even need to speculate. Here’s the WARP value produced over the years for position players split by whether they are 28 or under vs. 29 and over:

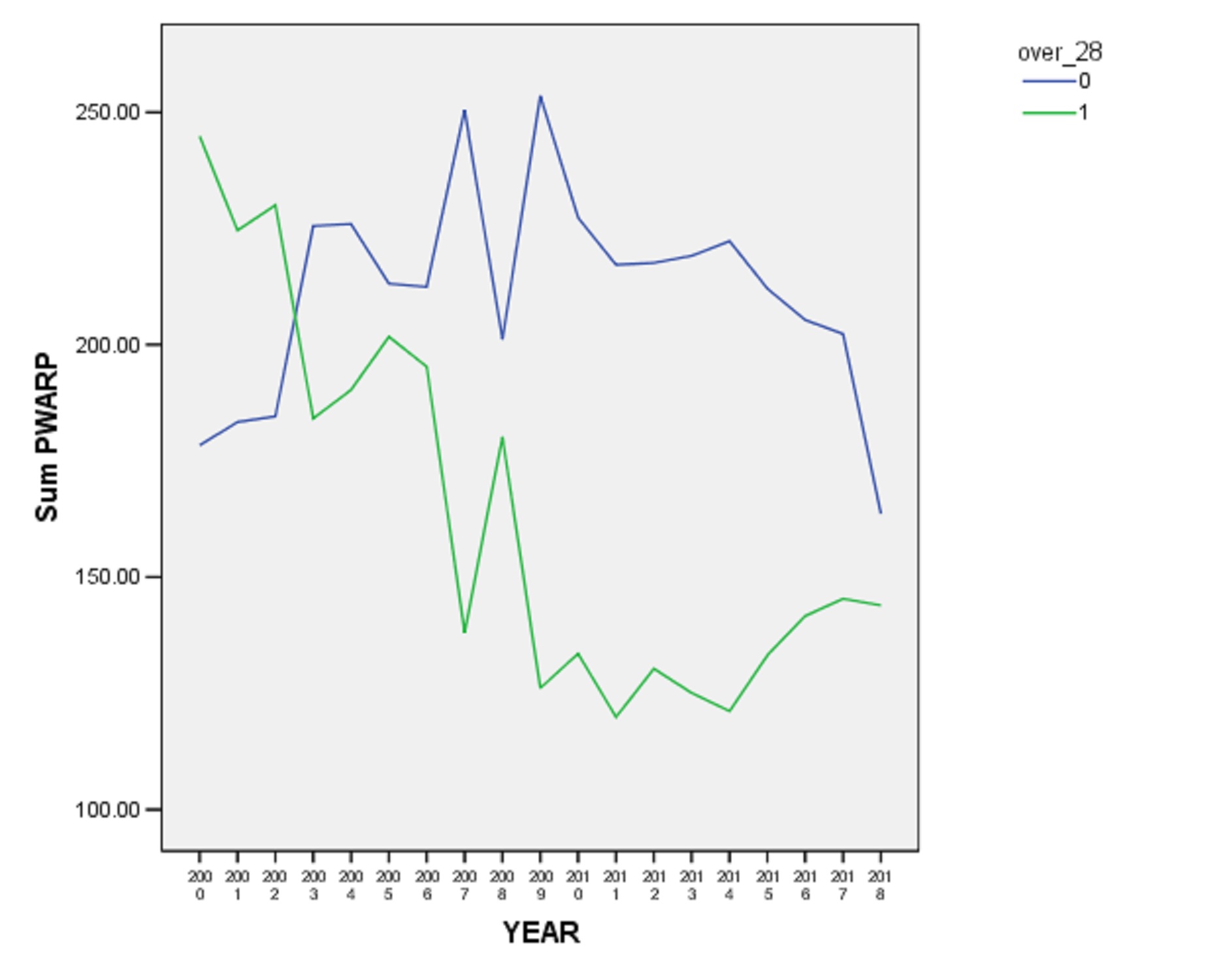

Here it is for pitchers:

Teams are already looking for younger players. It’s not surprising. With the universe of potential players expanding thanks to the global outreach of the game, there are now simply more humans capable of doing the things that get one placed on a major-league roster.

Right now a 29-year-old with a limited track record is still comparatively cheap, because he’s still in his arbitration years. In the analyses above, we assumed that teams would continue to search for players in the same ways they had in the past. But their incentives would change, and we have to assume that their behavior would, too. The good players would still have jobs at 30, but now that marginal 29-year-old who debuted at 26 isn’t as cheap, and maybe a 23-year-old could do the job just as well, for cheaper. At that point, you don’t need a 23-year-old superstar, you just need someone who can “do a job.” And there are a lot more “do a job” players out there than superstars.

I don’t think we’d see baseball become a 30-and-under sport in the proposed system, but teams would now have every incentive to view a player’s 29th birthday as an expiration date. Do we really want to keep this guy around if we’re going to have to pay him that much? And if the reach of the game keeps expanding, then there will be more 23-year-olds available to take his place. (Then again, that might keep happening under the current system anyway.)

Teams will gladly keep the players around who are young and good (and now in the new system, cheaper for them), but inasmuch as the system benefits players who weren’t wunderkinder, teams might just let them move along to the next part of their lives. If the system screws over the young superstar and the older, third-tier players, perhaps the MLBPA might look at this and wonder whether it’s actually all worth it to have the next hotshot prospect play a few meaningless games in September.

However, if we wanted to get rid of service-time manipulation, it would be as simple as setting a free agency age (after your age-28 season), and expanding arbitration by one year (age-25 through age-28). It would make the game a little better and probably a little younger. There would be winners and losers, but players and owners as a whole would come out about equal in the deal. So, next time you guys are all sitting down to talk about the upcoming CBA, keep this idea in mind. It could work.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Of course, the internet could be wrong. Guys like Kopach and Reyes whom the internet clamored for, fragged their elbows. A guy like Hoskins who the internet kind of ignored because they were not particularly young and athletic, proved he was beyond ready while at the same time the more touted Crawford and Kingery in the same organization crashed and burned. The internet fretted that Soto was being called up too soon, of all things, and he was up to the task from the start, even as the internet claimed Acuna was being falsely imprisoned at AAA and then struggled just a little when he arrived to Atlanta.

Or if that is too nutty, could just acknowledge the truth, that in certain circumstances teams have the bargained right stretch their initial six years of control out to nearly seven years.

In short, teams are trying to make the kind of smart decisions about how to best deploy their young talent that BP has championed for 25 years.

I'm also in favor of players pushing for the first three years' base salaries increasing to $1M, $2M, and $3M. Unlike Oldbopper, I'm willing to wait out a work stoppage for this subject to be resolved in a manner that transfers more money to the guys I pay to see on the field.