Not too far from Williamsport, home of the Little League World Series, lies Ricketts Glen State Park. Covering 13,050 acres (or 4,350 baseball fields) in parts of three counties, it is a jewel of a state park. Its Lake Jean is large enough to accommodate both a busy swimming beach and lily-padded arms and stream-fed nooks for secluded fishing, and its woods are seamed by hiking trails leading to a fire tower, blueberry and mountain laurel thickets, old growth forest, a beaver dam. And there is its greatest treasure: twin chains of waterfalls cascading through the park’s southern half.

Before the outbreak of the American Civil War, Elijah Ricketts and his brother purchased 5,000 acres near remote Kitchen Creek, land which had been part of Haudenosaunee territory prior to European colonization. Following the war, Ricketts’ son, Colonel R. Bruce Ricketts, bought the land from his father and then more, amassing more than 80,000 acres near Red Rock Mountain for timbering purposes. Within that original 5,000 acres, in terrain too difficult for logging endeavors, lay two waterfall-studded gorges. Eventually, Ricketts’ heirs sold the land that would become the state park to the Pennsylvania Game Commission; a plan to create a national park site in the area was derailed by World War II. But a state park emerged all the same, and thanks to extensive labor in building and maintaining the craggy trails against both time and catastrophic flooding, hikers are able to walk Ganoga Glen and Glen Leigh beside the 21 waterfalls created by Kitchen Creek’s two branches.

On Saturday, the waterfalls were bigger than I’ve ever seen them, fat with this wet season. The spray misted my glasses; the trail itself ran with water following gravity’s pull; every little overhang added its own tiny cataract. It’s not a place to walk distracted. A significant portion of the trail through both gorges comprises rough stone steps—not a rail or fence in sight—a few feet and sometimes a few inches from the rushing water. On the Ganoga Glen side, part of the lower path is entirely gone, consumed by the swollen creek, and hikers get by as best they can, rock to rock, foothold to foothold, in the soft, black earth.

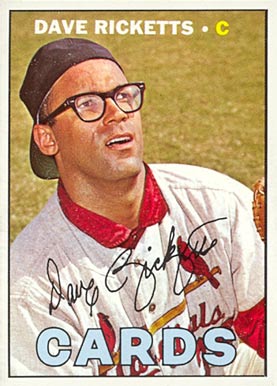

There is not much in the state park or its history to connect overtly with baseball beyond memory—taking mitt and ball on every camping trip of my childhood—and coincidence: a pair of brothers from Pottstown, Pennsylvania, Dick and Dave Ricketts, both played Major League Baseball. Dick Ricketts had a three-year NBA career and pitched one season for the St. Louis Cardinals; Dave spent five seasons in St. Louis (not overlapping with his brother) and a final year in Pittsburgh, and then went on to a considerable coaching career in the Pirates and Cardinals organizations. Though during Dave Ricketts’ playing career he was primarily a backup or third-string catcher, a 2008 tribute after Ricketts’ death by Derrick Goold from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch attests to a far more significant impact as a mentor, quoting Yadier Molina on the centrality of Ricketts’ coaching and support to Molina’s success: “’I’m here because of him,’ Molina said. ‘He made me into a catcher. I wasn’t a catcher when I got here. I learned a lot from him. He was like my dad, there for me since I was 17. He meant so much to me.’”

Insofar as I can discern, there is no genealogical link between the Ricketts of the park’s history and these two people. They were undoubtedly gifted athletes but nevertheless not particularly noteworthy in the grand scheme of athletic performance after their college years, during which they helped Duquesne University to an NIT championship in basketball. But an idle curiosity wondering if any baseball threads ran through the weave of this state park I love so led me to learn about two more players in the era of baseball I know least about—not far enough into the storied past to take on the mythos of pre-WWII baseball and not recent enough to belong to me—and that feels like time well spent.

Today was the last day of September. It rained all day, which shouldn’t have felt unusual, but did anyway. This was one of the driest summers we’ve ever had. The rain felt like a restoration of something. The steady drizzle knocked dead leaves off the trees and onto the ground, into puddles where they formed a gross brown sludge that squelched under my feet, and on the trees the leaves that were still in the process of dying were shiny orange against the green of the leaves that don’t die. Summer is finally, finally over.

I woke up early this morning. I cleared out of the cozy lane house in which I spent the night as quickly as I could. I took three buses across two bridges, and I hustled through the rain with no jacket and no umbrella, trying to siphon warmth from my cup of coffee. I was in a hurry because I really, really wanted to get home in time to watch all the baseball. Which shouldn’t have felt unusual because I’m supposed to care about the baseball. But it did feel unusual, anyway.

The 12:05 universal start time arrived. I was still in transit. I held my phone in my non-coffee bearing hand, trying to rub the raindrops off the screen as I walked without spilling any coffee. I flipped back and forth between the Dodgers and the Rockies and the Brewers and the Cubs, and in between those, I checked in on my sad, hapless Blue Jays. It all seemed very urgent. Back in June, when I travelled across the continent to see those same sad, hapless Blue Jays, I was worried that I didn’t care about baseball anymore. When I was out there in the Dome in the blazing heat, every color blazing under the sun, I remembered what the caring felt like.

An interminable three months later, I have been worrying about how little I care about anything anymore. Baseball is the least of my concerns. I haven’t watched the Jays in weeks. Today I watched them lose, and I watched five other games besides that, and it didn’t feel like a tiresome obligation. It was fun, and I cared. When I looked outside, it was grey and wet and windy, muted and cold, and the colors seemed brighter in comparison. High above everything, windblown atop the chimney of the apartment building that sits right on the water, the huge and ancient heron that has sat there every autumn and winter for almost my entire life looked out over the ocean. Its ragged feathers fluttered, and for hours it stood there without any other movement, long after all the games had ended. The rain continued.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now