Americans love a spectacle, and this is why Red Sox-Yankees games—as perfect a historical avatar as we have in our still-fledgling country—carry a special weight. Red Sox-Yankees games are, above all else, a production: storied franchise against storied franchise, colonial city vs. colonial city, the Yankees vs. literal redcoats. It is the greatest rivalry, not just of baseball and not just of our time, but of America itself. Rivalry is not essential to spectacle, but it lends the proceedings a heightened quality palpable even to outsiders, a frisson of added excitement, a breathless intensity.

The more intense a spectacle, the more immersive it is. At the turn of the 18th century, panoramic paintings were all the rage for the wealthy elite and lower classes alike. Special viewing theatres were constructed for the 360-degree images, sort of an early IMAX, that depicted themes such as the Peloponnesian War or city views of far-flung places like Constantinople or Rome. Much is made of the bandboxes of the AL East, but looking at Fenway, all velvety bunting and tiered green grandstands tightly circling a gleaming, jewel-like infield, it’s not hard to imagine the sense of wonder that flooded our 18th-century counterparts stepping into their own immersive experience. Panoramas offered viewers an out-of-body experience, the Aristotelian notion of ecstasy: the ability of drama to lift one above quotidian concerns and shoot our souls soaring into the stratosphere. Playoff baseball, rivalry-driven playoff baseball at that, in America’s foundational cities is an ecstasy of which Aristotle could only dream.

Today, very few panoramic paintings survive. The originals, massive undertakings, were damaged from constant display, having been changed out each season and shipped all around the world. Around the turn of the 19th century, panoramas began to lose facetime to the burgeoning art of film, with panning shots soon doing twice what panoramic paintings were able to in a fraction of the time. And yet the American love of spectacle remains, from Thanksgiving Day parades to fireworks extravaganzas to Yankees-Red Sox games.

The opening of this ALDS delivered on the American thirst for spectacle, unrolling a panorama across nine innings that would have melted off our forebears’ faces. Boston’s best pitcher, the cryptid Chris Sale, legs like bridge cables, seemingly willed the ball into the strike zone, pairing his mid-90s fastball with his Houdini slider. He struck out eight in just over five innings of work and somehow this was an off night for Sale, who walked two and allowed five hits.

Offensively, the Red Sox struck quickly against J.A. Happ, as J.D. Martinez did what Boston hired him to do and clobbered a three-run homer in the bottom of the first inning. It’s hard to remember Martinez was ever not a member of the Red Sox, so perfect is he a fit for that club; it’s even harder to remember JDM was a D-II product who at one time was unceremoniously cut by the Astros. (Don’t forget that. It’s probably going to be important in a little while.)

In a quiet offseason, Boston signing Martinez felt both like an inevitability and an impossibility, as baseball writers chewed their pencils and waited for news, for some spark to shoot across the sky in an especially barren winter. Boston provided the fireworks then, and now again on a crisp October evening, the harvest moon waning like the season itself, the bang proving commensurate to the buck.

Meanwhile, homegrown superstar Mookie Betts continued to make his own wind out in right field.

If 37,000 people could will a runner to be out, Gleyber Torres would be toast here.

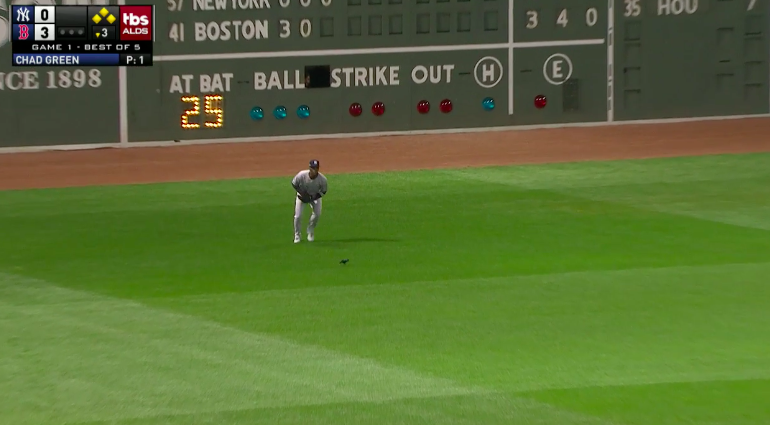

Boston would add two more runs off reliever Chad Green, who was summoned in the third inning, giving the Sox a 5-0 lead, and it seemed like the rout was on. Some scene-stealing birds even showed up, all oh excuse us no one told us there’d be cameras present, because in the US of A, even our wildlife is fame-hungry.

But spectacle depends, in part, on juxtaposition: lulling the audience with soft music, a gentle flicker of lights; and then, suddenly, thunder strike, cymbal crash. When Sale was lifted in the sixth, it was with two men on and just one out. He was replaced by Ryan Brasier, no. 12 on the poster of Reliever Haircuts, who managed to collect one out but allowed two runs to score.

A call to the pen and cue the broadcast images of Sale, his facial expression suggesting he was doing shots of Draino over the commercial break. Brandon Workman (no. 9 on the poster) walked the bases full and escaped, but then needed to be bailed out himself in the seventh inning, only to have Matt Barnes (no. 16) allow another run to score. Suddenly the Yankees were within two runs. Somewhere, a zoetrope rattled into motion.

Any dramatic theorist, from Aristotle to Scooby-Doo, will tell you that in order to have true drama, there must be something at stake. The answer to the mystery can’t be too obvious, the desired outcome not too easily achieved. Otherwise, there’s no transcendent moment, no ecstasy; the audience is not lifted away from their lives, and the spectacle falls flat. This is the dramatic challenge of a series between the high-flying offenses of Boston and New York. Steamrollers do not make great dramatic instruments.

Crane-posing Craig Kimbrel does, though, especially when he surrenders a home run to Aaron Judge, a baseball-destroying golem crafted out of coils of tungsten and bits of clay from the grave of Babe Ruth. In the contest of “machine engineered to produce strikeouts” vs. “machine engineered to hit home runs,” the meteorite-born dinger machine won:

Judge had led off the ninth inning, so now Kimbrel had a slim one-run lead with which to navigate the trio of Brett Gardner (in for an injured Aaron Hicks), Giancarlo Stanton (Boaz to Judge’s Jachin), and Luke Voit (possibly a young African bush elephant in a human suit).

Kimbrel decided the spectacle, tonight, was in his control. He struck them all out.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now