Violent clashes are a historic part of sport.

“Kill! Kill! Kill!” we chant continuously through every televised sporting event, the only sound detectable over our shouts being the opening and closing of the front door as our families leave us for the last time.

The attempts to contain the natural brute force and gore of professional sports have been fruitless. The desired result—a more civil version of our most barbaric impulses—have been vague. Unclear. Foolhardy. Trying to control human movement as endorphins are flowing, nerves are exploding, and bodies are flying is an exercise in pure arrogance.

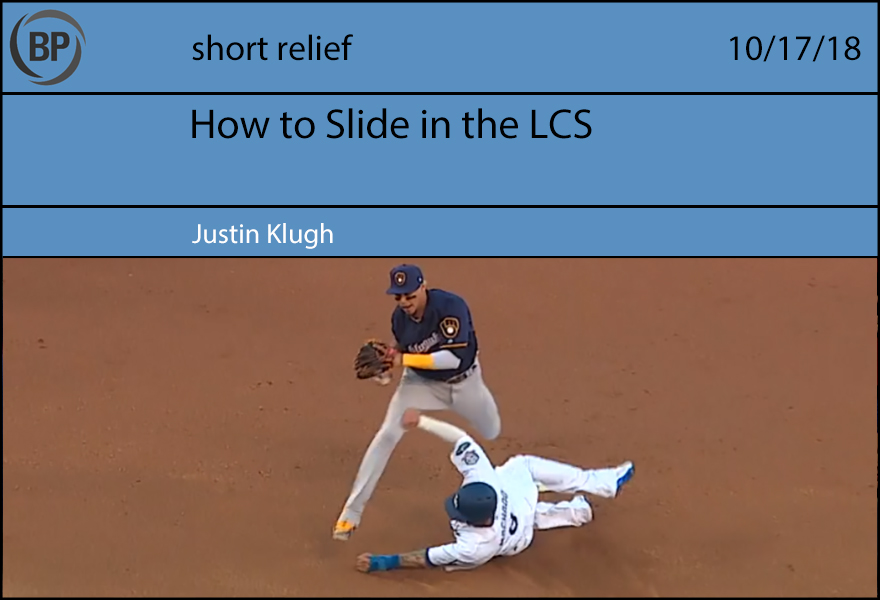

Some cried foul of Chase Utley’s takeout slide of Ruben Tejada in the 2015 NLCS that broke both Tejada’s leg and the rules of baseball by forcing the league to soften a type of play that had bruised, battered, and fractured infielders’ legs for generations. On Monday night’s NLCS game, Manny Machado slid into second and attempted to disrupt a double play in a move filtered through the new rules, which resulted in a sort of slap fight with Orlando Arcia’s leg. With the situation at its most ridiculous, it is, of course, time for a change.

The disruptive slide has become an intrinsic part of playoff baseball. Each postseason begs the question: Who will be the projectile? Who will own the kneecap in their crosshairs? What lesson will we learn? That lesson need not be a physical one. Takeout slides can simply be altered to include verbal attacks, rather than bodily ones.

Imagine your innermost truth, locked in your heart, sealed behind your rib cage, insulated by layers of guts, but then suddenly screamed by a man in a dead sprint heading straight for you. As he goes to the ground, he says, out loud, something you’ve kept hidden your entire life; not loud enough for others to hear, but loud enough for you to know he knows.

A verbal lashing can injure a man not in the knee or shin, which heal, but in the mind, where we are all the most vulnerable. The human brain is easily scarred. Tricked. Manipulated.

By taking advantage of this, modern athletes can both follow the current rules and create a disruption of the defense that goes beyond a single play: An injured player leaves the game. A rattled player must stay in and impact it.

Imagine trying to hit an 0-2 splitter two innings after the opposing shortstop has yelled at you about the time you killed your neighbor’s dog and buried it in the park. Focus on the game with the catcher crouching behind you who just held up a cue card reading “SHE NEVER LOVED YOU” as he slid harmlessly into the second base the previous inning. Get your head on straight enough to take a pitch on the corner while you feel the stare of the right fielder who just mentioned the time you bought a video game instead of a birthday gift for your grandmother.

What’s he doing out there? So small in the distance. Yet full of secrets. What else does he know? How does he know it? Oh god, what I have done? Grandma just wanted a pack of licorice and I… I had to have Call of Duty. What’s that? “Strike three?” That’s fine, I… I need to go sit down anyway.

Rather than explain an inconsistent set of rules each year, players have the power to destroy each other mentally, not by shattering bones and tearing flesh. That way, the hurt stays on the inside, where we can’t see it, making the game cleaner. Better. More civilized.

Paul Allen died this past Monday. He was a lot of things—technology entrepreneur, real estate developer, philanthropist, melted playdough-shaped museum builder, sunken battleship finder, guitar player, and, oh yeah, sports team owner. He purchased the Portland Trailblazers in 1988 and then, in 1997, the Seattle Seahawks. The latter he bought when the franchise had literally loaded up moving trucks to relocate to Los Angeles, and Seattle civic leaders practically begged him to save them for the city. He did, and in 2014 the Seahawks won the only “Big 3” professional sports championship I and this region have experienced in my lifetime.

As a Seattle sports fan online, that’s the predominant image I have seen the past 12 hours: Paul Allen, surrounded by the coaches and staff who had achieved something he bankrolled, holding the Lombardi Trophy, showered in confetti. It’s the way baseball’s championship presentation will go in a few weeks. The Dodgers, Red Sox, Astros, or Brewers will pile onto, around, and through each other in jubilation. Their season, their career, for many their entire lives have been built toward the singular goal of achieving what they have just achieved. The newly minted champs will be allowed their brief foray into delirium—it makes for excellent television, after all—and then we will go to commercial.

The broadcast will return to a hastily constructed podium, a small wall of stern looking people trying to keep the players off of it (we don’t want gleeful profanities making it on air). On the podium will be the three pillars of the sport: Commissioner, owner, sponsorship representative. The Series MVP will receive a Dodge Avenger, Chevy Camaro, or some analogous sports car. Then everything will shrink down and Rob Manfred will say “It was an excellent series and a record breaking one too and we’d like to thank our sponsors for another successful season” and then he’ll present the trophy to, first and foremost, the owner.

The players, many of whom will most likely engage in a bitter work stoppage against that same owner in a few years, will cheer. The fans, whose tax dollars most likely built the stadium that that same billionaire has wildly profited off of, will roar. The owner himself will smile and hoist the trophy skyward, probably with far too much gusto and triumph given how little physical toil, exertion, and struggle he put into this victory relative to those surrounding him. Everyone will clap, because this is sports, and this is winning, and that’s the whole point of all of this after all.

Right?

I woke up at 3:30, my son’s knee in the small of my back. I’d had a nightmare about my daughter: we were walking along a sidewalk when she broke out into a run. Because of dreamphysics I couldn’t catch up, and I watched her run in front of a truck. It didn’t hit her, because it couldn’t; I couldn’t dream it that way, couldn’t imagine the sight or the sound of it striking her little body. Instead I stood there helpless, trapped in my heavy-handed metaphor, as she ran away.

I had to write at 5:30. It’s one of the few times I get to write, because after putting the kids down I’m usually too tired to be creative, and one may as well work after the short sleep than before. But I woke up at 3:30, which means I wrote poorly at 5:30, before giving up and heading for work. It was a lost day. There have been a lot of lost days.

Baseball players have lost days as well; Yasmani Grandal had a very public one the night before, a night where he couldn’t seem to get the glove where it needed to go. In May we shrug at the two-inning starts and golden sombreros; in October we snarl. But it’s surprising to me how rarely those days string together, in the grand scheme. Players have rotten seasons, sometimes, but there’s usually some physical trigger, some bone spur floating somewhere. Players get old. But it’s not often we trace a bad stretch of baseball to a divorce, or the loss of a loved one, or homesickness or simple ennui. David Cone told of his 1992 Skydome hotel room littered with aluminum and cigarette ash, but he still went out and posted a 2.55 ERA for Toronto. It’s probably that mystical athlete focus, that mental training – I want to hope that it is.

But then I read about P.G. Wodehouse, of Jeeves and Wooster fame. Wodehouse was living in France when the Nazi armies invaded; unable to retreat to England, he planned to drive to Portugal only to have his car break down two miles up the road. He was captured and interned, and only after international pleas was he provided a typewriter for his cell. There, separated from his family and country, sixty years of age, living in a photonegative of his decadent lordly gardens, he sat and wrote… a crime caper, Money in the Bank, a novel indistinguishable in style or in quality from any of his dozens of works.

There’s something admirable in how baseball players and breezy pre-war novelists can hypnotize themselves out of their daily miseries to produce their valuable content. I wish I could do the same. My bone spurs must be elsewhere.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now