When I stepped into the subway car parked on the fourth floor of the Whitney Museum, I was standing in a life-sized cartoon. The floor heaved beneath my feet and I could hear the train rattling on the tracks. The papier-mâché passengers had lavish faces four times the size of mine and they were doing things that subway passengers always do: reading newspapers, staring at the doors, holding things on their laps. There were spaces for visitors to sit and so I did, just to stop in disbelief. This personable creation was more than a sculpture. It was a habitation.

This was my introduction to Red Grooms’s Ruckus Manhattan, a decade after the debut of the “sculpto-pictorama” installation. Ruckus was a walk-through, hands-on collection of moving sculptures. It positively boiled with energy, New York energy with all its absurdity and its constant, pounding motion. I practically walked into the jaws of a giant dragon made of money, wrapped around the Woolworth Building and chomping at visitors. I laughed aloud. I took my turn getting stuck in the revolving door. The layers of color and caricature were the most vivid I have ever seen.

I missed Ruckus Manhattan’s 1976 debut, but I have heard stories. It belonged to a time when New York City was filthy, dangerous, and bleak, when even a walk was a risk. It was into this that Ruckus Manhattan erupted, alongside punk rock, gonzo journalism, and body art. It said something. It shouted into the city’s decline as if to say, “Hey, people! Look at city life! It’s hilarious. Soak it in, you gorgeous denizens of irony!”

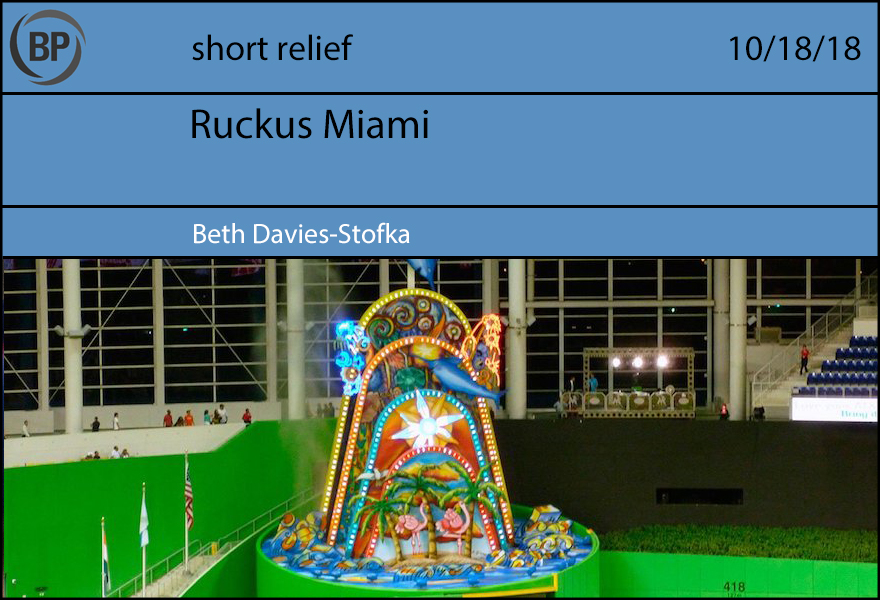

How disappointing, then, is the Marlin’s “sculto-pictorama,” Homer. He is Ruckus Manhattan in form only. Colors layer upon colors, caricatures layer upon caricatures, and he is fun enough, I suppose. He animates to home runs in a swirly kind of way that makes me think of ice cream. But Homer doesn’t say anything. The social commentary is missing. Where is Grooms’s extravagant embrace of a slightly crazed humanity? Humanity is missing altogether! Poor Homer is just functional, which is about the last thing you want said about you, if you are supposed to be a work of art. All Homer manages to say is “Whee!” The CGI screen can say “Whee!” It can go one step further and just read, “Applause.”

Now, Homer is moving. Maybe he will get a second chance, sitting outside Marlins Park, or double down on its own garishness in some minor league stadium parking lot. Time will tell if he learns to speak, or what he will say if he does. I hope that in situ, Homer will say what Ruckus Manhattan said all those years ago: “You gorgeous, crazy, kitschy people, I love you!” And he will say it Miami-style.

There was blood, if not from bodies then in the air. And rain, rain to wash it away. First was the so-called football tackle of Fred Merkle by the great Christian Gentleman himself, who later laughed it off like something he had heard at the cinema, a passing joke worth five cents and a beer. There were stolen signs, the bastards, an outrage that drew everything from questioning just what that third base coach was doing in the sixth to wondering if switching the rotation could make recompense. It was by all accounts, a fiasco, a media circus: Mathewson received a gold watch from the denizens of the New York Theater scene—an attempt to woo the burgeoning modern city’s newest celebrity—and Ty Cobb followed them all with pen in hand in an attempt to tell voracious readers just what the boys must have been thinking; he would know.

The Giants came out swinging, taking the first game from Philadelphia 2-1 behind the work of Mathewson–notching his 28th-straight scoreless playoff inning. But then the sun set and rose, and then set and rose again, and he noticed something strange between home plate and first base.

The ensuing hours brought discord. A wrong: something tangible to point to, shouting, an alibi to distract from what Wasn’t but which nevertheless screamed what Should Have. Outcomes which brought with them not expectations of deliverance but instead a promise that it would all go according to plan: instead, the horror of contingency, the controversy over one of the club betraying their own. Surely this would be remembered, etched into the history books as the greatest scandal the game had yet to face. The things, they say, would never be the same.

The next day it rained, and then it rained for five more days and the Athletics went home with the crown. The next year, historical unrest would give way to Theodore Roosevelt falling short second in the US Presidential election as a bull moose, and two years after that the Europe that was no longer. Christy Mathewson was there, in France, and the ground was wetter than he could ever have imagined.

(h/t Andrew Rice and Dan Gomez, for research assistance)

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now