They brought baseball under the cover of cannon fire; within weeks of the Battle of Manila, soldiers were playing baseball in the fields, demonstrating their Americanness to the new Americans. Designed to supplant the local sport of cockfighting and instill cultural values and language, it proved a clumsy and effective propaganda, as the sport swept through the county in the early decades of the twentieth century. But as the United States lost its interest in the Philippines as a people, as the American empire transitioned from a cultural to a financial exercise, baseball slipped away; the game grew into a very different symbol as the fields disappeared.

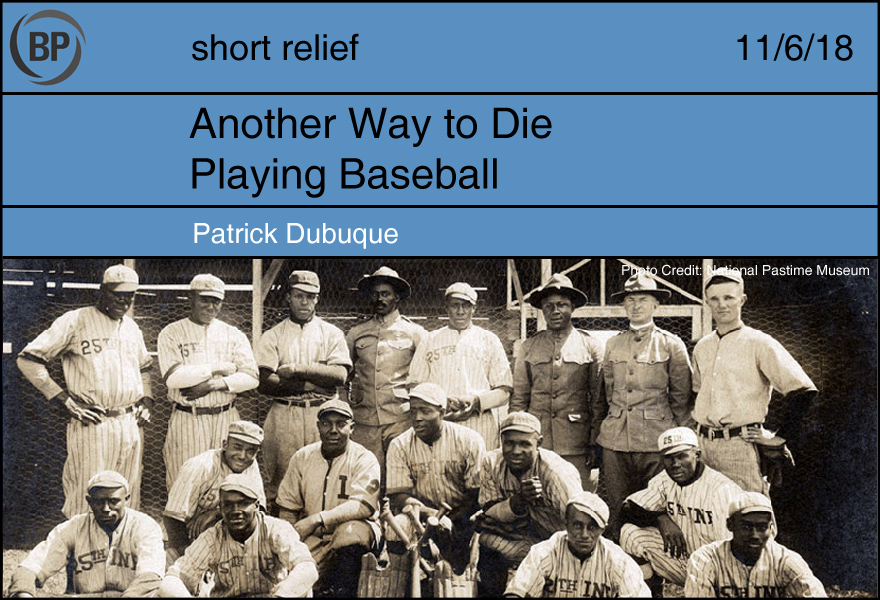

Amidst that heavy symbolism, in the early years of the occupation, this happened, as described in Sport and the American Occupation of the Philippines: Bats, Balls, and Bayonets, by Gerald Gems:

For all its conflict, death feels like the opposite of baseball. It is a game of phantasms. Opponents rarely touch each other, except through the universe-spanning reach of the tag of the mitt; first basemen step off the bag after a putout, just before the lunging foot of the runner, as if repelled magnetically. Even the proof otherwise fails to impress. Ray Chapman’s death hardly seems possible, a hundred years later; it may as well have been typhoid. The death of Alfredo Edmead, forty years ago in front of a thousand people in Salem, is almost too horrific to remember, let alone repeat. There should be nothing tragic about baseball; no harm or destruction should leave its confines.

So to imagine a man dying because he slid on his own dagger — a dagger! — is nearly impossible. I can’t imagine playing beer league softball with a phone in my pocket. And yet, just to prove that the ridiculous is not, by default, comic, this talented and anonymous man was carried from the field and became just a soldier, just another dying man in a city where so many had already died for the sake of changing flags. One wonders if, like Edmead, they continued the game as he passed from sight, or if the illusion of peace had been shattered. I assume they played on. The battle, and the war, must always be fought.

As far as I’m concerned, the year has two seasons: baseball and skiing.

The perfect year for me is a year with the slimmest transition between when one of these ends and the other begins. This spring, I got my wish for no down time at all: on March 30th, I was in my sweaty long underwear on the living room floor of my friend’s house in Colorado, stretching my quads as I watched Max Scherzer go six scoreless innings and strike out ten. The autumn is always a little harder, though – November stretches long between the World Series and the first snow substantial enough to ski on. So that’s my limbo, that quiet season where the perpetual hum of baseball is gone and the thrill of the ski season hasn’t started yet. I want my team to go deep just like everyone does, but if they can’t, I can pray for early snow instead.

Skiing gets into your blood the way baseball does. There’s the same kind of obsessing over reports and predictions, the same urge to drop everything, jump in the car, and just go when moment is right. The old timers reminisce about the perfect days they had in years past and bemoan the way the sport has changed. There are even similar superstitions for both – I always wear the same exact pair of socks when I ski, out of paranoia over boot problems. (Yes, I wash them overnight. Usually.)

I also cling to what’s left of the old season as I’m waiting for the new. My non-skier baseball friends were appalled that I was willing to miss the beginning of the Nats’ Opening Day game to get a few more runs in on the ski slopes. What kind of baseball fan was I, anyway?! But it was my last chance to ski last season, and the baseball season looked the way it always does in March: endless. Would I change that choice now that the Nats’ season is over, end my ski day early to catch a few more innings of Max’s season? Maybe – but probably not.

It’s the same adrenaline in both sports, the same thrill. I’ve narrowly avoided heatstroke in 100 degree weather at Nats Park, and warded off frostbite with chemical toe warmers in -28 in Canada. It’s the commitment you make to the sport you love, despite the strain, the time, the expense. As Jimmy Dugan would say about baseball, and I would apply it to skiing too: the hard is what makes it great.

Clouds are blowing in; a storm’s coming. All over the Northeast, the lifts are starting to spin. I’d better get my gear tuned up. It’s gonna be a long winter, and I’m planning on being out in it.

As painful as the regular season is, the off-season is doubly so, thrusting us into the bleakness of winter, unarmed and alone. Suddenly we have far too much time to obsess over all of the thoughts baseball allowed us to push into the recesses of our minds. The routines built up over six months of daily commitments are gone, and it becomes all too apparent that as much as we hate baseball, nothing is good enough to replace it. Winter is dark, cold, and depressing, and even though we know spring will come eventually, we somehow never really know it.

To help us with our baseball withdrawals, might I suggest a project! Uploaded to the Library of Congress and waiting for your perusal are 15 digitized copies of AG Spalding’s annual Official Base Ball Guide. Each volume––clocking in at around 180 pages––provided the public with updated rules, constitutions, season recaps, essays written by a wide swath of baseball-related figures, and advertisements for various Spalding products. Much of the contents are fairly mundane, recaps of seasons complete with pages of rudimentary statistics, but nestled amongst these pages are some real gems.

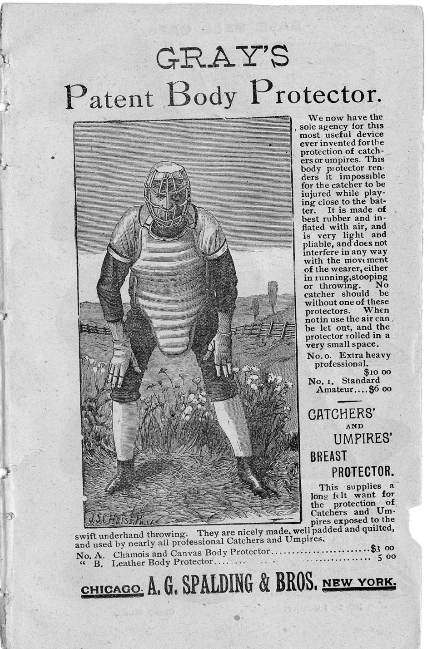

For instance, the final 10 pages of the 1889 edition are comprised of ads for Spalding’s baseball gear, ranging from gloves to shoes to bats. One of these products is the newly created full-body protector for catchers and umpires, accompanied by maybe the most terrifying illustration ever used to sell sporting equipment:

The 1911 edition kicks off with a quotation from 19th century humorist, Henry Wheeler Shaw, whose pen name was Josh Billings. The quotation itself is fine if not slightly irrelevant to the ensuing pages. What will really keep me up at night is the use of quotation marks around Josh, implying that only the first half of the name is illegitimate, rather than it in its entirety:

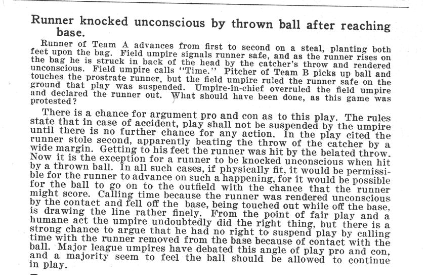

In 1933, the guide’s editor, John B. Foster, introduced a new feature in which he attempted to lay to rest some of the most hotly debated rulebook questions of the previous season. The feature, titled “Knotty Problems,” is well worth your time:

As I have plainly demonstrated, there’s something for everyone in these guides. So next time you find yourself listless and missing baseball, open a random edition of Spalding’s Guide and share your newfound old wisdom with the world!

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now