It’s been a hundred years since baseball last accepted organized gambling. In the wake of the 1919 World Series scandal that nearly killed the sport, the National Commission, then the governing body of Major League Baseball, turned itself over to a single commissioner: Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a federal judge out of Chicago.

Judge Landis had been favorable to the American and National Leagues in an antitrust suit brought by the upstart Federal League. In addition to formalizing and enforcing the color line for decades, Landis banished anyone remotely connected to gambling interests from baseball, establishing a strict enforcement policy that has largely lasted since. Even Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays were briefly banned for the seemingly harmless act of working as casino greeters in Atlantic City.

The Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (colloquially known as PASPA) was passed in 1992, functionally banning sports betting nationwide, with three exceptions carved out. Nevada was permitted to continue its state sports-betting operation, three states were permitted to continue operating teaser and parlay-style betting through their “sports lotteries,” and New Jersey, as a state with regulated casino wagering, was given a one-year window to establish its own sports betting system.

New Jersey failed to do so in the early 1990s, but political winds in the state changed in the early 2010s. After a 2011 statewide ballot question favoring sports betting passed with 64 percent in favor, the legislature passed various laws designed to challenge PASPA. The cases kicked around the legal system for most of the decade, but earlier this year the Supreme Court held PASPA unconstitutional in Murphy v. NCAA, returning the issue to the individual states. Although Murphy left it open to Congress to ban sports banning entirely, there appears to be little political will to do so. More states are legalizing and regulating sports betting by the month.

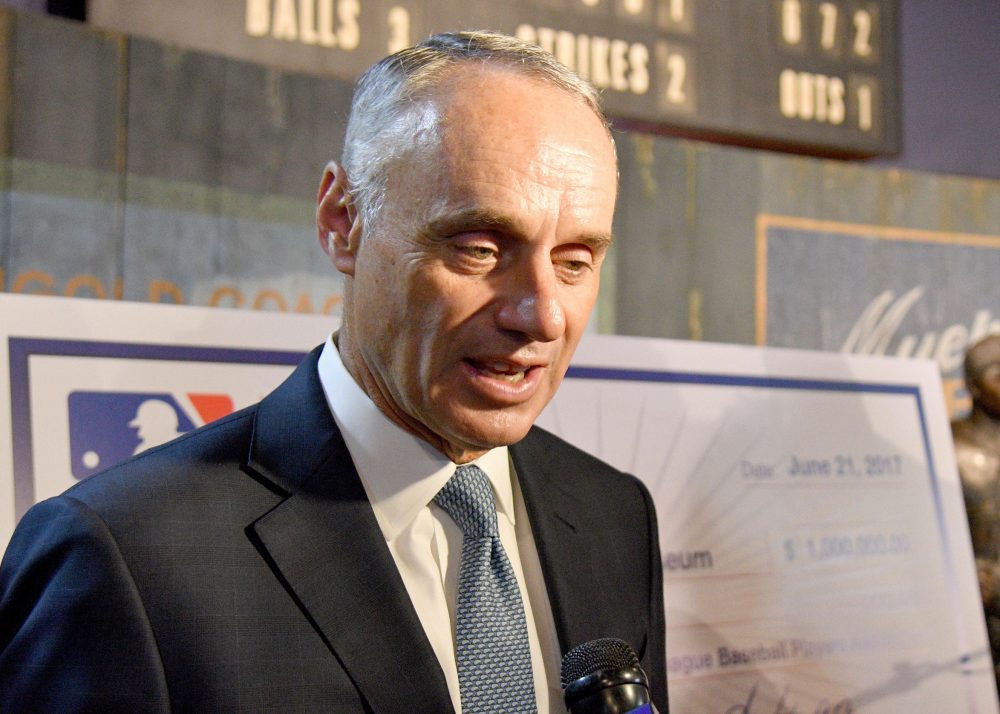

As recently as a half-dozen years ago, former MLB commissioner Bud Selig derided sports betting as “evil.” The downfall of PASPA was necessarily going to change things, and even before the Murphy ruling MLB had already started drifting in this direction by partnering with and promoting DraftKings daily fantasy wagering. Earlier this week, MLB announced a deal with gaming giant MGM to name them the official gambling partner of Major League Baseball. The deal is worth $80 million over four years. That sounds like a lot at first glance, but only adds a little under $700,000 per team per year to the kitty. That’s a pittance in the overall baseball climate.

The partnership will include the usual licensing and promotional aspects, which are ironic and hypocritical given baseball’s long-held intolerance for gambling promotion, but also inevitable in the 21st century marketplace. It also includes a wrinkle that has hit a nerve with part of the analytics community: MGM is getting some vaguely defined exclusive access to Statcast data, the tightly-held crown jewel of Major League Baseball Advanced Media.

There is one specific situation in which access to Statcast data could make sense for all involved and provide limited ethical quandaries. With the rise of mobile betting, in-game betting has become far more prominent. The biggest enemy of in-game betting from both the bookmaker and gambler perspective is time. Even for the simplest in-game bet, a win/loss line, a bookmaker needs to get the updated information about the state of the game, run a win probability matrix advanced enough to create a correctly balanced line, and post the new odds. And every second lost doing that reduces the amount of time for the gambler to make a bet. When commissioner Manfred mentioned the slow pace of the game as a positive in relation to modern gaming, this is what he meant—among the four major pro sports, only football has similar pauses between plays.

Major League Baseball, of course, already has the best and fastest data stream in the world for the information bookmakers would need. If you’ve ever followed a game without being able to watch or listen to it, you probably figured out pretty quickly that MLB’s own Statcast-powered products, such as the At Bat app, provide not only the most detailed pitch-by-pitch and at-bat-by-at-bat information available, but also update quickly and fairly reliably. In that sense, letting MGM access certain MLBAM data feeds is entirely sensible, and in line with deals other major sports have struck with gambling companies.

Yet this hill also gets slippery fast. Once you’ve established microbetting and access to great data, it becomes tantalizing to start offering wagers on all kinds of things: odds on the next pitch type or pitch outcome, or an over/under on pitch velocity, exit velocity, or spin rate. That’s where you start getting into situations where information gaps and even outright manipulation could occur.

If you have concerns about baseball being crooked, one of the things that makes you sleep easier is that it’s harder than you’d think to effectively manipulate the outcome of an entire game—weird line movement plus weird stuff on the field that doesn’t look right is how fixed games have been uncovered since Hugh Fullerton and Christy Mathewson did it in 1919. It might be easier to manipulate, or at least seem easier to manipulate, the outcome of a single pitch. The Associated Press has already reported that measures will be put in place to ban players and employees from disclosing “confidential” information that would affect the wagering outcomes. Yet that prohibition itself could change the landscape significantly given how much of the media industry relies on sourced information.

It’s also not clear whether MLB can even offer MGM particularly exclusive access to public baseball statistics. A series of court cases last decade in which MLBAM tried to enforce licensure of statistics for use in fantasy baseball established that such use of baseball statistics is generally protected by the First Amendment, licensed or not. Baseball can control who has access to its feed, but it certainly isn’t going to be able to stop non-MGM gaming outlets from accepting bets on games, and it might not even be able to stop them from using the publicly available Statcast data for betting purposes.

Of course, the analysis to this point presumes MGM is only getting the type of Statcast-powered analytics you might see publicly posted on, say, MLB’s Baseball Savant affiliate. What if MGM is getting access to the otherwise private underlying Statcast streams that MLBAM currently only supplies to teams and its own analysts? That would create a heck of a tradeoff for gamblers. MGM would have the fastest, most vibrant betting options for baseball games—but they’d also be able to set far better lines than other gaming outfits. If you’re trying to create an honest wagering scenario for the public, the last thing in the world you’d want to do is hand over a bunch of non-public information to bookmakers.

Such access would also be an odd contradiction for the public analysis community. MLBAM has closely guarded not just the availability of Statcast information, which is quite limited and often only presented in already manipulated form, but they’ve tried to control who gets to analyze the information they’re willing to make public. This has widened the analytics gap substantially, especially in areas like quality of contact, pitching spin rate, and all aspects of fielding. Allowing baseball researchers and the general public access to that data would greatly enhance our understanding of the game. To allow gambling interests access to that data for their financial enrichment while continuing to stifle public research would be unfortunate.

These are complex waters for MLB to navigate, without easy answers. What we do know is that the century of strict separation between organized baseball and organized gambling is over, and that wall is not coming back anytime soon. Let’s hope the new walls are in the right places.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now