This article is part of the launch for Baseball Prospectus’ new hitting statistic, Deserved Runs Created, which you can learn much more about here.

We survived without computers. I know this, because I remember the day when my dad hooked up his brand-new Atari 400 computer to the back of our 12-inch Magnavox television, and the perfect blue of the memo pad lit up for the first time. I was born just on the edge of that transitional generation, of learning cursive and balancing checkbooks and just doing math all the time, constant manual arithmetic.

It still amazes me. We learned how to sail ships without computers. We learned how to do calculus. We built towers that didn’t fall down, most of the time. We engineered catapults to knock them down anyway. We built a robust system of philosophy called “utilitarianism,” founded on the principle that the good of an action is evaluated by summing the effects of that action, which is the kind of formula that would make the world’s mainframes crash. The whole foundation of statistics as a field is “here’s math you could easily do but would die of old age first.”

The fact of the matter is that there is too much math in the world to do. There are too many things changing, and too many things too small to notice, for us to handle. At some point, they become too much for the computers to handle as well, which is why we have chaos theory and undetectable earthquakes, but it’s not an even fight. At some point, we fall back on intuition, and given how under-equipped we are, we’re forced to bestow that intuition with some sort of supernatural superiority, the “gut feeling,” that we can’t prove because we can only intuit that our intuition is better.

We’re all lousy at intuition, and wonderful at lying to ourselves about it. The honest truth is that computers are far better at intuition than we are, because in order to know what feels “off” you have to know what’s “on.” In order to do that you have to constantly reassess the average of everything, then re-rank your own experience against it.

Test your own, by comparing these three anonymous lines:

| Player | G | HR | AVG | OBP | SLG |

| Player A | 156 | 38 | .259 | .342 | .535 |

| Player B | 154 | 38 | .280 | .348 | .527 |

| Player C | 158 | 38 | .266 | .343 | .509 |

These all seem like pretty similar players, right? The second one a touch more batted-ball dependent, the third a little less strong, but all pretty good hitters. And you’d be right, about the latter. Not the former.

Here’s the breakdown:

Player A: 1991 Howard Johnson, 141 DRC+

Player B: 1996 Dean Palmer, 121 DRC+

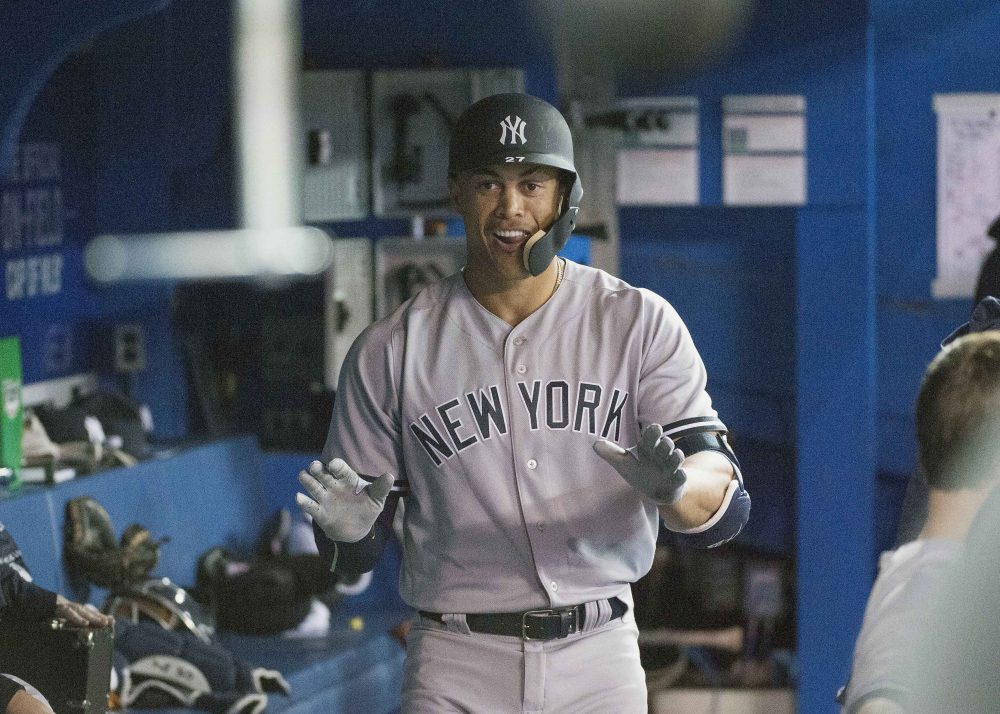

Player C: 2018 Giancarlo Stanton, 114 DRC+

Baseball is fortunate to have escaped the seismic shifts of so many other sports, where the talents and performances of other eras are nearly unrecognizable. (And not just other sports: try to explain the greatness of the movie Duck Soup without adjusting for era.) But they’re still there, and they’re nearly impossible to account for manually, without having to resort to sweeping generalizations like “steroid era” or juiced-ball era” to throw out entire swathes of production.

This is all to say that we should celebrate the index stat, that simple 100-based scale with such a humble aim: just to give context. It’s hard to imagine how we lived without them for so long. Sabermetricians have always tried to make their stats look like other stats: True Average mapped to batting average, FIP molded to look like and compare to ERA. It’s easy to understand the motivation—these statistics carry an emotional value in them that is hard to resist, as with the .300 hitter and the 2.00 ERA—but even they fall prey to the same loss of scale as their unadjusted counterparts. If a .300 average means different things in different years, does that hold true for a .300 True Average?

Instead, 100 doesn’t say anything, except above average or below. And it does it instantly, for every season in every run environment for any statistic we want it to. We should have more index stats: K%+, so we can stop comparing Mike Clevinger’s career 9.46 K/9 to Nolan Ryan’s 9.55. HBP%+, so we can note that Ron Hunt was getting plunked when nobody else was getting plunked, as opposed to that imitator Brandon Guyer. Some might note how stale these references are and accuse league-adjustment as a backward-looking drive, and this is true. But we’re always looking backward, always comparing the new with the expectations already set. The index stat just forces us to be honest.

There’s always resistance to a new statistic, especially one so outwardly simple and so internally complex. We tend to stick with what we know, even in the case of formulas that are supposed to tell us what we know. But if your resistance is that it seems too complicated, too counterintuitive, too “black boxy,” I encourage you to consider why you feel that way. Because the real world is infinitely more complicated than baseball, where all the pitches go in one basic direction and the baserunners are only allowed to travel in four directions. Baseball statistics based on mixed methodology are almost impossibly intricate. So are skyscrapers and automobiles. That’s why we have computers—to take the guesswork out of them.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now