This article is part of the launch for Baseball Prospectus’ new hitting statistic, Deserved Runs Created, which you can learn much more about here.

By now, you’ve heard that DRC+, our new offensive index stat, represents a step forward in detailing the ways a hitter contributed to scoring runs. Those who have given the leaderboards their own personal eyeball test hopefully feel the gravity of common logic, and some uplift from new insights, like this one: On a per-plate-appearance basis, Mark McGwire is one of the most dominant hitters to pick up a bat, and perhaps the second-best that most living baseball fans have ever seen.

Wrapping your brain around this morphing of history is never an instant process, and for some it won’t take. That’s OK. A few moments spent in the space beyond preconceived notions might prove revelatory, though.

The 1998 home run race, McGwire’s impossibly glorious moment in the sun, has been remembered, suppressed, complicated, and smothered in the baseball consciousness over the course of only two decades. It stands as a towering mental image of the hulking red-headed slugger, but also conspires with other related bits of history to keep his prowess at the plate from being fully recognized.

This statistic that zeros in on deservedness asks us to consider McGwire for all the ways he was more than homers, for the ways he maximized his abilities where so many other sluggers have fallen short. It asks us to put him in a new conversation, even if it feels strange at first.

***

Below is the all-time career DRC+ leaderboard, if you haven’t seen it. The minimum doesn’t matter much, but we’ll set it at 4,000 plate appearances, which allows Mike Trout into the fray.

- Ted Williams, 180 DRC+

- Barry Bonds, 175 DRC+

- Lou Gehrig, 168 DRC+

- Mark McGwire, 164 DRC+

- Babe Ruth, 161 DRC+

We can’t blame anyone for struggling with this, nor would we ask that this be taken as a hard and fast ranking—BP is providing standard deviations to reflect the uncertainty that digits on a screen sometimes overshadow.

The digits exist, though, products of a great deal of research into which contributions are most likely to create runs. McGwire’s reputation fails to match up with his extraordinary rate of contributions, and there seem to be two main reasons for that.

One is the admitted use of steroids/supplements. It seems extremely likely that they helped keep him on the field for his mid-30s peak, but the extent to which they assisted in powering his performance past his contemporaries is unclear and likely overstated in the popular imagination for reasons we’ll enumerate shortly.

The other is McGwire’s awkward place in MVP and Hall of Fame debates. His career has never mingled well in those rooms, and DRC+ won’t do much to change that. His rate stats are rosier than the counting numbers diminished by injuries, and he never provided the defensive or baserunning value of the in crowd, for whom these spaces exist. The fact that they host most discussions of baseball greatness has always kept McGwire down—his mastery of hitting glossed over not because it’s difficult to see, but because it sticks out like a sore thumb.

The dismissive adjective “one-dimensional” bubbles up in McGwire analysis with comical consistency. Applied in the hitting/running/fielding sense, of course, it’s completely fair. Too often, though, it escapes its bounds and turns into a misguided characterization of his bat. Observe such a spillover occur in this CBS Sports article exploring his Hall of Fame resume:

He wasn’t an especially deft fielder (range, etc.) for the most part despite being pretty sure-handed. So I guess his statistical case revolves around only home runs.

Still, his home-run hitting ability also landed him tons of walks and his career .394 on-base percentage is 81st in MLB history.

See the snowball effect? He was just a hitter, and his main claim to fame was homers, so he is his homers, more or less.

DRC+ would strenuously disagree.

***

Dan Moore, of the Cardinals blog Viva El Birdos, wrote of McGwire:

If McGwire had one skill, he leveraged it better than almost every other player who had it.

Amid many excellent and insightful assessments of McGwire’s career, Moore’s line cuts to the heart of what DRC+ shows us.

The skill in question? Certifiably insane 80-grade power.

He could turn a piece of lumber into a Howitzer in the blink of an eye. Yet others with similarly explosive power failed to produce like McGwire. Take 1992, for example. A young Juan Gonzalez edged McGwire for the MLB homer crown, 43 to 42, simultaneously illustrating the ways in which power does not necessarily act as a lever that opens the floodgates for other good outcomes.

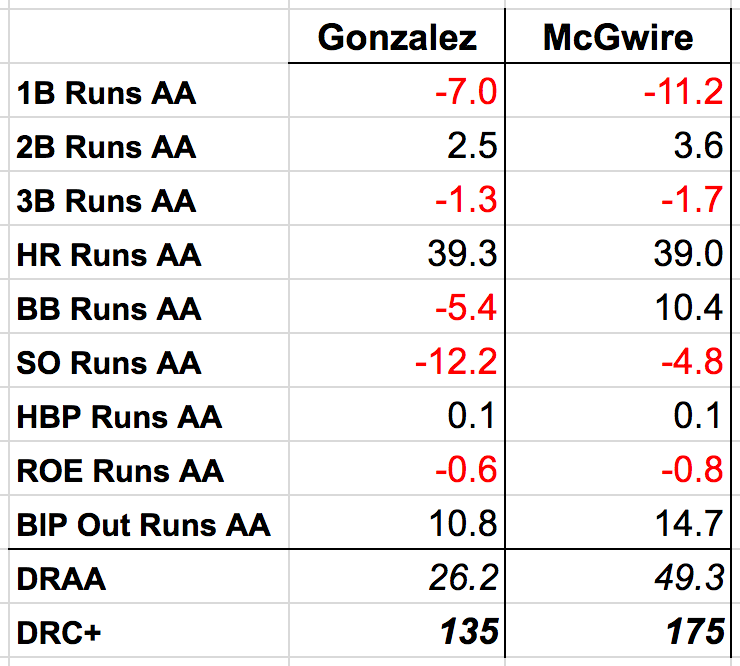

These values, available for every season, show the shape of a player’s contributions, compared to the average position player. McGwire and Gonzalez are predictably similar in some ways: Fewer singles than average, fewer triples than average, nary a reached-on-error in sight. McGwire, however, aides his team in the plate appearances where he doesn’t get anything to hit—his above-average walks more than balancing out the strikeouts. His discipline also shows up in the column called BIP Out Runs AA, which essentially shows McGwire avoiding many of the batted balls routinely converted into outs.

It’s not just that McGwire was “pitched to less frequently,” as many said in brushing past his on-base skills. His time in Oakland was spent developing a mode of attack that accentuated his strengths and minimized his weaknesses.

The detailed plate discipline stats we use to gawk at Joey Votto don’t exist for McGwire’s career, but Retrosheet data available at Baseball-Reference gives some sense of his evolution.

Having set a rookie homer record (that Aaron Judge would break in 2017), McGwire did inspire fear in pitchers—often carrying one of the lowest rates of strikes seen in the league—but he had to tinker with the best ways to exploit it. From 1988 to 1991, his (relatively) diminished slugging numbers hint at imperfect pitch selection, and for a few of those years, his BABIPs wail about it. DRC+ gives him a significant benefit of the doubt for the extreme lows on that front, especially in 1991, which does contribute to his standing here.

However, in that time, he remained strong in the areas of the game over which a hitter exerts the most control: He walked a lot, nearly as much as he struck out. Eventually, DRC+ looked prescient, even though it is a model that computes a player’s most likely past contribution.

In those leaner years, McGwire seems to have tried on some strategies, like swinging at the first pitch a lot. Eventually, his strikeout breakdowns—more and more of the looking variety—began to indicate that he had a firm grasp of his situation: He inspired pitchers to be careful. Given his extreme talents and physical limitations, he was best off hunting for pitches he could drive, and letting borderline offerings go to the umpire for judgment. That’s not nearly as easy as it sounds. Just ask Joey Gallo or some such slugger. But McGwire did it beautifully.

A few years down the line, he was there with both his preternatural ability and learned approach, ready to capitalize on the state of play in spectacular fashion.

***

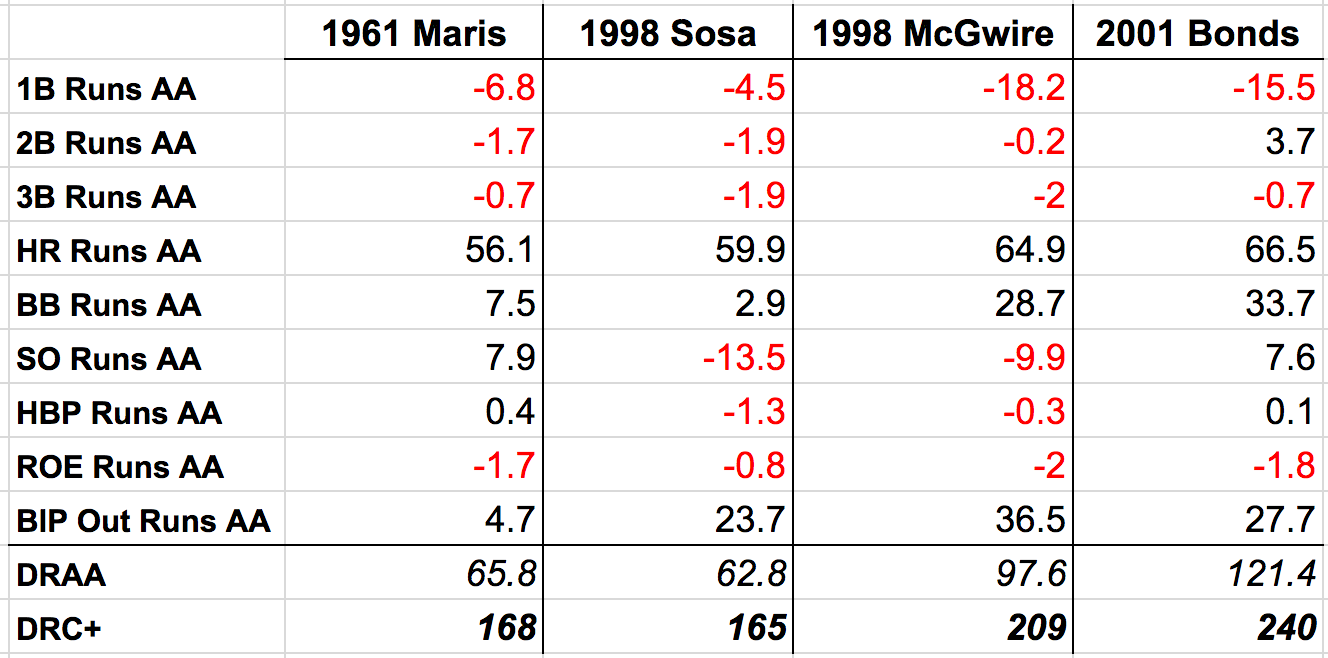

In 1998, McGwire posted an all-time great hitting season, checking in with a 209 DRC+ that ranks 12th among all full seasons. Reprising our run values chart from earlier, we can compare his world-beating power display to the others that captivated baseball, and see just how well he leveraged his biggest asset.

Better than almost anyone.

We find McGwire clearly out-producing 1998 Sammy Sosa and 1961 Roger Maris. He lost out on the MVP award to Sosa in 1998 largely because the Cubs had a better overall team than the Cardinals, but his otherworldly power was accompanied by similarly impressive ability to reach base—.470 OBP!—and make his contact count.

It was the crowning achievement of a five-year stretch from 1995-1999 in which McGwire (189 DRC+) was the best hitter in baseball—in an explosive offensive environment where many played with some chemical assistance—by 20 points of DRC+ over the second-place Barry Bonds. That’s the same advantage, for instance, that Trout has on Anthony Rizzo, the eighth-best hitter over the past five seasons.

Failing health forced McGwire out of the game quickly after that, and Bonds one-upped him on every front, a truth that perhaps could have been appreciated as an era-defining joy, but instead went down in a heap of consternation. That’s no one’s fault, but it’s everyone’s loss. A touchstone offensive talent is often misremembered or overlooked, mumbled and hurried through.

What Mark McGwire deserves has very little to do with the arguments that have shouted him down, and even less to do with a new, promising offensive metric that has no clue what it waded into.

It has everything to do with the way he played baseball, pursuing his talents to their extremes, and finding awe-inspiring new ground. That resonates through the game’s storied history, and in today’s stars, even if the name “McGwire” does not.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

I'm struggling to understand statements like this I've read over the past week about DRC+. I see the point of stripping away the "luck" from a player's performance, but to say that anything other than what a player actually did is his "most likely past contribution" is rather nonsensical. His most likely past contribution is exactly what actually happened.

Using DRC+ seems better suited for projections than retroactively determining how well a player "should" have done and using that to rewrite history.