“Leadoff hitter” and “cleanup hitter” are labels that naturally bring to mind specific player types, skill sets, and statistics—and maybe even cause you to picture certain star players who fit those established molds particularly well. To a lesser extent the same is probably true of the “number-two hitter” label. Close your eyes and visualize it. What do you see? Is it a speedy contact hitter with minimal power? Maybe a switch-hitting middle infielder who bunts a lot? And boy does every announcer love to praise them for doing “the little things” to help their team win, right?

Throughout much of baseball history, the standard qualifications required in a no. 2 hitter seemed to be some combination of: above-average speed, good bunter, switch-hitter, able to move the runners over, good at hitting behind runners, willing to take pitches, stays out of double plays, good contact hitter, handles the bat well.

Of late, those qualifications have been simplified to: must hit.

For decades, the prototypical no. 2 hitter was basically just a slightly better version of the prototypical no. 8 and no. 9 hitters, which never made much sense. If the two options for a specific hitter are “bat him second” or “bat him last” then there’s a disconnect happening on the way to the ultimate goal of scoring the most runs. There are 156 players in MLB history with at least 2,000 plate appearances as no. 2 hitters and more than half of them posted a slugging percentage below .400, one-third of them were below-average hitters, fewer than 10 percent of them had an OPS+ of at least 110, and as many of them slugged below .300 (two) as slugged above .500 (two).

As far back as the 1990s, and certainly by the mid-2000s, sabermetric websites like this one and numbers-based simulations were showing the wisdom of using the no. 2 spot for an impact bat rather than a bat-handler. I can remember playing around in the early 2000s with David Pinto’s lineup optimizer tool, which was based on the numerous studies of how batting orders could maximize run scoring. You entered in the hitters and their batting lines, and it would spit out “optimal” orders that almost always featured one of the best hitters in the second spot. And the reaction would usually be dismissive, or at least confused, as if somehow the numbers wouldn’t actually play out that way in real life.

As recently as five years ago, it was treated as a foreign concept. Here in Minnesota it was viewed as roughly equivalent to the moon landing when Jack Goin, who at the time was more or less a one-man analytics department for the Twins, approached manager Ron Gardenhire with data showing that Joe Mauer should bat second. Gardenhire’s quotes back then were revealing in that they showed how he viewed the topic from the starting point that the no. 2 hitter must meet the long-established qualifications.

People say Joe Mauer should hit second or whatever, but do we really want “man on second base and Joe Mauer coming up,” and he’s shooting it over the other way? I don’t know about that. That’s not his game. Just hitting is his game.

Gardenhire was ever so close to having a eureka moment, but he never quite got there, at least in Minnesota. He listened to Goin, moving Mauer to the second spot in the order … for about a week. And then it was back to his preferred no. 2 hitter mold: Nick Punto, Alexi Casilla, Matt Tolbert, Luis Rivas, Cristian Guzman, or another “scrappy” middle infielder with above-average speed, below-average power, and a sub-.700 OPS.

In fact, in 13 seasons with Gardenhire as manager all but two of the 10 hitters who batted second most often for the Twins posted a slugging percentage below .400 in that role and all but two were middle infielders. Five years later, it seems both quaint and a little sad that “give Joe Mauer more plate appearances than Nick Punto” was anything but an obvious notion. (Mauer has spent the past three seasons regularly batting second for the Twins, who now have a robust analytics department and a different manager.)

The idea behind the shifting identity of no. 2 hitters is a simple one: You want your best hitters batting the most often, and moving from 3-4-5 to no. 2 can equal an extra 30-50 plate appearances per season (and fewer plate appearances with two outs). The reason that no. 2 is often the choice instead of no. 1 is that batting second allows for more runners on base. It’s kind of a best-of-both-worlds solution relative to the leadoff and cleanup spots, adding more plate appearances but also leaving some RBI chances.

Think of how often, in your baseball-watching lifetime, you’ve been rooting for the no. 1 or no. 2 hitter in the lineup to reach base in the ninth inning so that the no. 3 or no. 4 hitter would have one last chance to make an impact before it’s too late. Now ask yourself why that lesser no. 2 hitter was there in the first place, if you were just hoping to see them avoid making an out so that a better hitter could come to the plate.

And with less and less focus on individual RBI totals, and more focus on team-wide run production, the idea of an “RBI spot” has less importance. Why bat someone no. 4 or no. 5 just so they can individually drive in a bunch of runs thanks to coming to the plate with lots of runners on base, when you can instead bat them no. 2, bring them to the plate more often, and score more runs as a team?

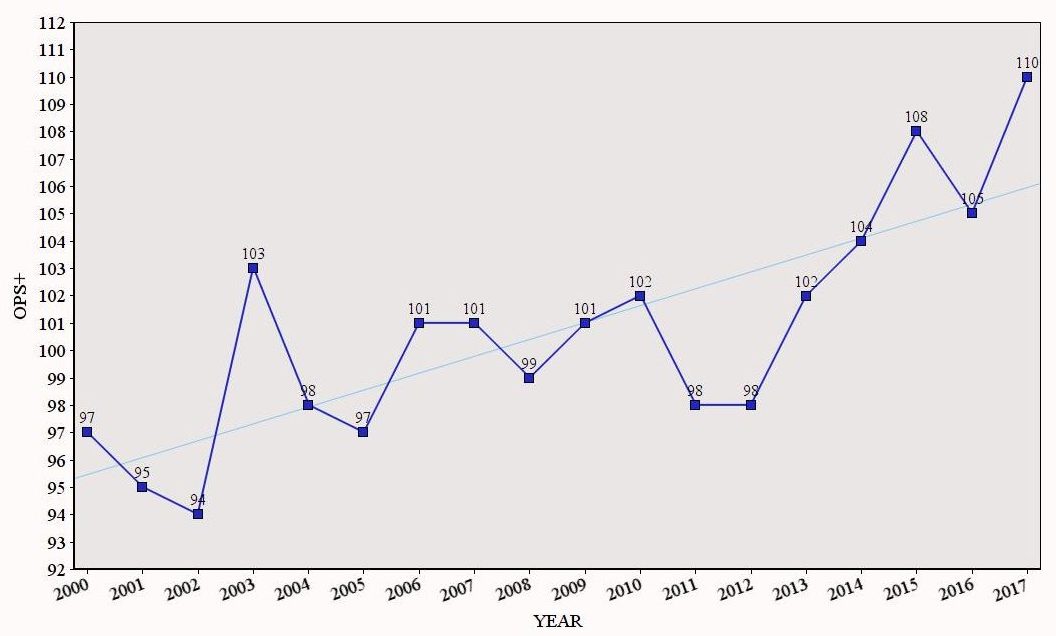

It’ll be a tough sell for some people—fans, media members, and even those within the game—but for the most part actual decision-makers in MLB front offices and coaching staffs have definitely bought into the new view of the second spot in the lineup. Here’s a chart showing the collective OPS+ of no. 2 hitters across baseball each year since 2000, with a 100 OPS+ representing an average MLB hitter.

The upward trend is undeniable.

Eight times from 2000-2012, the no. 2 hitters—receiving the second-most plate appearances in the lineup and batting directly in front of the most potent bats—were collectively below-average hitters. During that 13-season span, no. 2 hitters produced an average OPS+ of 98. Not only have the no. 2 hitters collectively been above-average hitters in each of the five most recent seasons (2013-2017), in each of the past four seasons they produced an OPS+ higher than in any single season from 2000-2012.

Combined from 1900-2011—a span of 112 years, including one stretch commonly referred to as “the steroid era”—there were just 57 instances of a no. 2 hitter totaling at least 20 homers in a season. Combined since 2012—a span of just six completed seasons—there have been 19 instances of a no. 2 hitter totaling at least 20 homers in a season, including seven last year alone.

It’s easy to spot the same trend by looking closer at individual no. 2 hitters as well. For instance, the 10 players who logged the most plate appearances as no. 2 hitters from 2005-2007 were Edgar Renteria, Tadahito Iguchi, Michael Young, Omar Vizquel, Placido Polanco, Dan Uggla, Derek Jeter, Orlando Cabrera, Mark Loretta, and Mark Grudzielanek. Every single one of them was a second basemen or a shortstop, none of them slugged over .500 as no. 2 hitters, and their average slugging percentage as no. 2 hitters was .424. (If you’re curious, the top 10 from 1995-1997 averaged a .423 SLG and the top 10 from 1985-1987 averaged a .435 SLG.)

Now look at the 10 players with the most plate appearances as no. 2 hitters from 2015-2017: Josh Donaldson, DJ LeMahieu, Corey Seager, Kole Calhoun, Dustin Pedroia, Joe Panik, Kris Bryant, Martin Prado, Mike Trout, Francisco Lindor. That top 10 includes four former MVP winners, half the players aren’t middle infielders, four of them slugged over .500 as no. 2 hitters, and their average slugging percentage as no. 2 hitters was .480. Hell, even two of the middle infielders, shortstops Seager and Lindor, are impact bats who don’t fit the prototypical no. 2 hitter mold.

Managers slotting MVP-winning sluggers like Trout and Donaldson into the no. 2 spot has quickly become commonplace, and based on the early batting orders teams have used this season it’s trending toward becoming the new norm. Within the first week of the 2018 season, the following stars batted second at least five times: Mike Trout, Josh Donaldson, Kris Bryant, Aaron Judge, Joey Gallo, Manny Machado, Corey Seager, Anthony Rendon, Christian Yelich, Tommy Pham, Alex Bregman. Others who’ve already batted second multiple times this season: Yoenis Cespedes, Carlos Santana, Wil Myers, Avisail Garcia.

We suddenly seem very far removed from the days of slap-hitting, bat-handling middle infielders occupying the no. 2 spot in nearly every batting order, yet as recently as 10 years ago the idea of traditional “cleanup hitters” like Trout, Donaldson, Bryant, Judge, Cespedes, and Gallo as regulars in the no. 2 spot would have been treated as craziness. Baseball is certainly guilty of being slow to adapt and change in a lot of ways, on and off the field, but once a couple of brave teams were willing to put their best hitters in the no. 2 spot the rest of the league sure followed in a hurry.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now