Yesterday, in introducing Jed Lowrie, not Manny Machado nor Bryce Harper, as the newest member of the New York Mets, GM Brodie Van Wagenen said the following:

“I fully expect us to be competitive and to be a winning team and our goal is to win a championship and it starts with the division, so come get us.”

Setting aside the logistics of how a team that finished second-to-last in the division last year (with last place belonging to a Romero-zombie-level Marlins team) might entreat other teams to “come get them,” it’s worth taking some time to parse this phrase. Initially the sentence was quoted on Twitter as “come and get us,” a verb-conjunction-verb sandwich that carries a friendlier connotation due to linguistic overlap with “come and get it,” a phrase indicating something toothsome on the near horizon. “Come and get us” is playful, teasing, carrying notes of breathless laughter, a frisson of mischief.

But Brodie Van Wagenen, despite his resemblance to a TV news anchor crossed with Forever Young-era Mel Gibson, is a Serious Baseball Man, and does not traffic in mischief-adjacent turns of phrase. The actual quote is “come get us,” a cold, daring imperative. To refresh your memory, in case middle school English class is many miles in your rearview, an imperative sentence is a sentence that directs someone to take action, to varying degrees. Consider the imperative sentence:

Sign Manny Machado.

Depending on who is doing the speaking, that imperative can be interpreted in multiple ways:

- A request: “Sign Manny Machado,” implores the fan who has given many of their fan-dollars to the team over the years, fan-dollars they would like to see turned into the acquiring of talent and a team to root for in October.

- An invitation: “Sign Manny Machado,” suggests Scott Boras’s many binders. It is a room full of them, the binders; listen, can’t you hear their insistent hiss?

- An instruction: “How to have a good offseason, Step One: Sign Manny Machado” says Off-Seasoning For Dummies, a book apparently no one has read.

- A command: “Sign Manny Machado,” dictates the GM. “Here’s a twenty and a wristband for unlimited rides on the Centennial Wheel, make it happen.”

Parsing an imperative sentence is a bit trickier than other kinds of sentences, as there can be some contextual guesswork required in determining who, exactly, is the subject of the sentence. The subject, again for those of you who slept through whatever well-meaning attempts were made by your teachers trying to make grammar cool and fun, is the noun that tells us what the sentence is about. But in an imperative sentence, the subject is elliptical: the verb refers directly to the subject. The identity of the subject must be assumed, as must be the subject’s attention to the matter at hand. In other words, in order for an imperative sentence to work, there has to be an assumption of a listener, and a presumption of interest on the part of that listener.

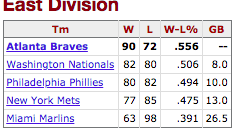

So to whom, exactly, is disgraced Postmaster General turned General Manager Brodie Van Wagenen speaking? If “come get us” is assumed to be the other members of the NL East, well, neither the linguistic ordination nor the order of the standings presents an overwhelming amount of support for that stance.

The second part, presumption of listener interest, is a bit more wooly, but there is certainly no abundance of information suggesting the other members of the NL East are looking anxiously over their shoulders at the encroaching Mets problem. So what then, is “come get us” without a peak from which to command, without an audience to instruct? “Come get us.” It’s a pathetic phrase, a wish from a child lying awake at their first sleepover, the lament of a people to the god who has abandoned them. In an off-season of sad imperatives and unheard requests, it is the saddest.

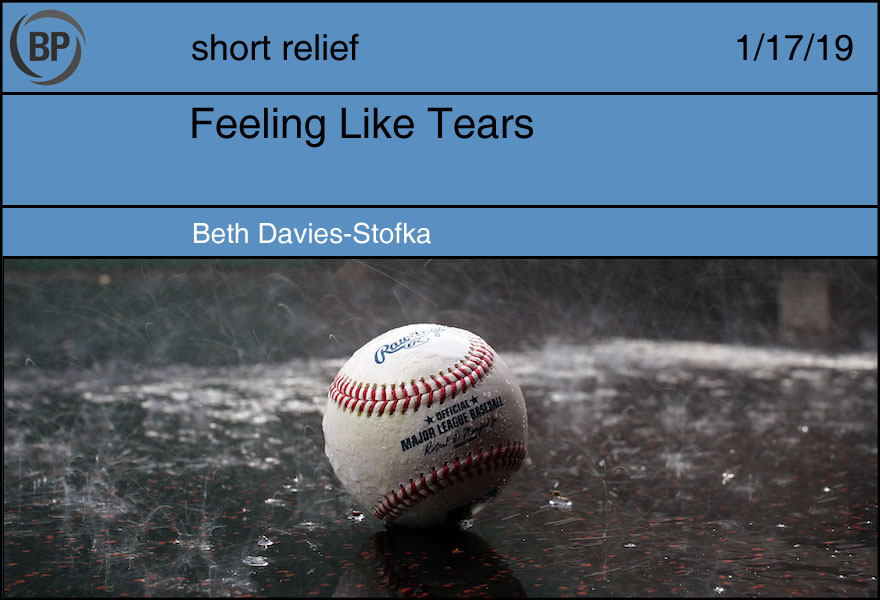

I have insomnia. I fall asleep almost as soon as I lie down, but sometime between 2:00 and 3:00 a.m. something enormous and powerful seizes me and I wake up, my body in a complete panic. It can take a long time to fall back to sleep.

I went through an exceptionally bad spell in the mid-2000s. It would take hours to get back to sleep. Sometimes I just stayed up, having failed to drive out the panic. That’s how I came to watch a streak of Australian Opens live. These were the peak years of the Federer-Nadal rivalry, producing matches so gripping that I was almost glad I couldn’t sleep. These were the years that Dick Enberg was covering the Open, composing brief spoken-word pieces about the two players and their contrasts. These pieces were so beautiful that I formed a desire to do the same. I never wanted to be a sportswriter in the broad sense, so much as I wanted to be the poet who could layer beautiful words into pure athletic performance. That was the birth of the dream that brought me to Short Relief.

Davey, my battle-ax cat, watched all those matches with me. I have read that cats can see green, so perhaps he could see the ball go back and forth. For some reason, he appeared interested. He would sit in my lap and stare at the television, and now and then he’d look back at me as if to say, “Are you seeing this?” I would muse that baseball could bring in a whole new fan base – cat lovers – by simply dying the balls green.

Davey died during the 2011 Australian Open. He had an infection and we gave him antibiotics, not realizing that there was an underlying infection from avascular necrosis—something I’d only heard of in a news item about Mike Napoli. The day after Davey’s death, his sister Bonnie came running to me because she needed comfort and so did I. Sweet cat that she is, she gave far more than she received. Since that day, we two have been joined at the hip.

Bonnie has never shown interest in television. Using a conservative estimate, she has been at my side for over 2,000 baseball games in the last eight years without paying the slightest attention to any of them. But because of her, I’ve never been alone. Now the 2019 Australian Open is underway, and Bonnie has pneumonia. We are giving her antibiotics, and she might rally, but at 17 years old, death is not a matter of if, but when. Will she be here for baseball’s Opening Day? Will she be with me while I sample every game, as has been our tradition? I don’t know.

If she is gone, what will the 2019 season feel like? It will feel like tears. Beyond that, I’m open.

There’s no proof that Winter Storm Harper getting its name wasn’t the product of Scott Boras making a phone call, but there’s also no way the National Weather Service just named it that without him activating his sleeper agent within their ranks. Ignoring the likely influence of Bryce Harper’s superagent on all of our national agencies, let’s instead put our focus where it belongs: On the weather-related nicknames of ball players past.

David “Stormy” Weathers: Shared name with Cybill Shepherd character from 1992 TV movie Stormy Weathers, in which she yelled “mea culpa, sisters!” at a bunch of nuns and shot her gun in the air. Said, “Wish my fastball was that high!” after having a temperature of 102.

Ken Cloude: No-hit the White Sox for six innings in his MLB debut before they came back and won. “White Sox Emerge from Cloude” read the Associated Press’ actual headline.

Jim “Sunny Jim” Bottomley: In a battle for a starting first base spot in 1931 after a lousy showing in the 1930 World Series, once said, “All I’m asking you to say is ‘Sunny Jim’ isn’t leafing this spring.” Said this after looking for and finding his hat, and tilting it over his right eye.

Andy “Rain Man” Benes: Supposed to start seven games that were postponed due to rain. Person who gave nickname was unaware or ignorant of origin of “Rain Man” term from Academy Award-winning film which has no connection to weather.

Jack Blizzard: Played for baseball’s least intimidating team of all time, the Plainview Ponies, in 1954. Was also least intimidating member of least intimidating team, going 0-for-1954 at the plate.

“Tornado Jake” Weimer: Burned hideously by newspaper headline in 1906, “Tornado Jake Weimer was only a zephyr.” Emotional wellbeing following this is unknown; likely sank to and remained at rock bottom.

Bob “Hurricane” Hazle: Was ready to give up and quit baseball forever due to a lack of belief in himself and also an extremely egregious and painful knee injury. Then, was promoted after another man’s extremely egregious and painful knee injury. Then, hit .403 in 41 games for the 1957 Braves. Presumably continued using knee injuries to get ahead in life.

Clint “The Hondo Hurricane” Hartung: Talked up as a generational talent as both outfielder and pitcher in training camp. 5.02 career ERA in 112 games. “In retrospect, it is easy to see that a lot of this was foolishness,” wrote one newspaper.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now