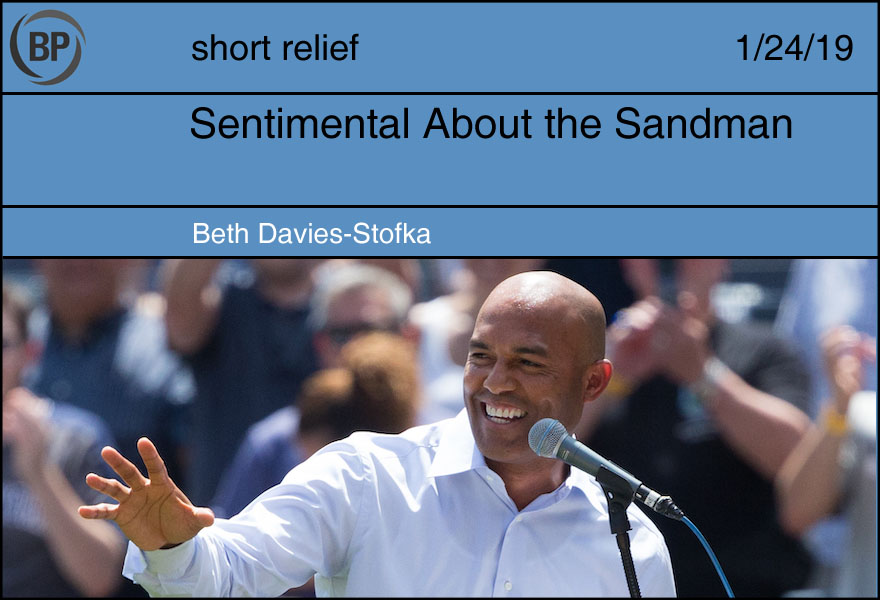

A woman stops at a market near Brooklyn’s McCarren Park. She buys mini-quiches and carrots on her way to visit her mother. They settle in front of the television to watch the game and grieve. A Yankees fan for 80 years, her father died last winter, so this is the first year that he won’t be watching with them. The two women cry when Mariano Rivera approaches the mound; their tears reflecting the unspoken significance. Rivera’s first pitch, a strikeout. A reminder that grief softens into hope.

***

A man drives a shuttle to and from JFK all day, and then drives a cab at night. He ignores the hemorrhoids, the aching back, the clot in his left leg and the cost of the Warfarin because he is earning food and college tuition for his daughters. For 162 days a year, the Yankees keep him company on the radio. He talks about his team with each and every fare as he loads and unloads their luggage. Reverence seeps into his voice when he mentions Mariano Rivera. There is pride in his voice, his head held high. Rivera’s wins are his.

***

A teenager sits on the boardwalk at Coney Island, her earphones a temporary respite from the parents who toss her against walls and doors, leaving purple welts and a broken heart. She listens intently as Mariano Rivera takes the mound, turning up the volume to drown out the ocean. She wants to hear every pitch. The world is bullshit, but Rivera is real. She thrills with every strikeout. Rivera is proof that the good guys can win, at a record pace no less. In his quick 9th-inning save, she finds the strength for her next battle.

***

A network profile celebrates Rivera’s integrity; the ingredients are kindness, sincerity, generosity, humility, and love. Yet Rivera talks about failure. Reflecting on the blown save that cost the Yankees the 2001 World Series, he says it was the seed of all his subsequent success. It was the weakness that made him strong. We watched Rivera win so we believe him. We believe that our stories can also end in triumph. Even joy.

Heroes come and go, but not Rivera. Rivera came to stay. He entered our lonely homes, our lonely labors, and our lonely lives, giving us hope. Giving us pride. Determination. Our memories of his pitching days linger like the scent of myrrh, Rivera the Sandman sweetening our dreams. He will be enshrined in the Hall of Fame, but he is already at home in our souls. We have a promise, that love conquers all. One hundred percent.

“Words most wished for can change. Something can happen to them, while you are waiting. Love–need–forgive. Love–need–forever. The sound of such words can become a din, a battering, a sound of hammers in the street. And all you can do is run away, so as not to honor them out of habit.” -Alice Munro, “The Jack Randa Hotel”

It didn’t feel like I thought it would. Maybe it’s having the ballots known to us now, the element of surprise no longer an element. Maybe it’s that it’s been ten years, and ten years is a very long time to feel one way about anything. Something can happen to those wished-for words, while you are waiting.

Not that the wish changed. Edgar Martinez is, and always has been, and always will be, my favorite player, but it’s more than that: It’s not that he is the avatar for the sport I love, it’s that he is the reason I love the sport. I am a baseball fan because of Edgar Martinez, not an Edgar Martinez fan because of baseball. Even now that he has been gathered into the bosom of Cooperstown, now that he has buttoned on the Hall of Fame jersey, even now I burn with white-hot fury when I hear a detractor sneer about the “Hall of Very Good.” No, the wish has not changed. It has been fulfilled. And I don’t know how to process it.

I have been lucky enough and privileged enough to have gotten things I wanted very badly. The Strawberry Shortcake dollhouse; acceptance into graduate programs; my name in print. These things have been associated with a feeling of triumph that lingers for several days, a warm and pleasant sensation to which I can return again and again, like stepping into a sauna on a winter’s day. I have also not gotten things I wanted very badly, and those disappointments, while stinging, have also sweetened the experience of getting things I have wanted, being able to lay another triumph on the scales as a contrapunto, the give-and-take of being alive. Believing in karma is a lazy substitute for engaged and rigorous spiritual practice, but the illusion that the world is not overly pernicious nor overly indulgent is an important one for me in order to continue on with the business of living without being crushed by a boulder of fear, or actively wanting to be crushed by a boulder.

Maybe, then, it’s that this win feels too big, too much like it’s tilting the scales in favor of a lollipops-and-head pats divine being rather than tooth and claw. I went to Catholic school; we always started the year lingering over the Old Testament for months and wound up rushing the New Testament.

Ten years is a long time. Early on, it looked like there was no hope for Edgar ever to make it to the Hall of Fame. 2013 wasn’t his lowest point, vote-wise, but it was my nadir of hope that Edgar would ever make it in, the year the writers saw it fit to vote no one into the Hall. Hope waxed and waned over that decade, sometimes within voting years–an increase in vote share would be offset by another precious year slipping away. #EdgarHOF became at first a rallying cry, then every year he didn’t get in, hammers in the street.

I just checked Baseball Reference to make sure I had the year right when no one went into the Hall, and clicked to expand the list. There was Edgar’s name, and in parentheses behind it, “HOF,” and Reader, it took my breath away. Words most wished for can change, but maybe because they become words you don’t know you have a language for yet, words you don’t recognize until they’re staring you in the face.

“This is actually nice. I don’t usually have anyone to talk to.”

Ian Clarkin stares off into the distance as we pass through Chinatown. The sights and sounds whirl past, but he’s seen it all before. He sways with the train as it races through downtown. Tourists are taking selfies on the sidewalk overlooking the river. He pays them no mind.

“It wasn’t always like this,” he says with lifeless eyes that yearn for yesteryear.

Clarkin sits alone in a window seat, his suitcase perched on the cushion next to him. The train is mostly quiet; winter in Chicago doesn’t exactly bring out the most chipper of personalities. A woman in her 30s is reading The Kite Runner a few rows back. Across the aisle, a man in a custodial uniform lets out an occasional suppressed chuckle as his headphones help distract him with a Mitch Hedberg comedy album.

Like many a young hurler, Clarkin dreams of green grass and blue skies, of the sound of the ball hitting the mitt or the roar of the crowd. But instead, enveloped by the noise from car horns, the monotonous whoosh of the train door opening and closing, and the chatter of commuters, those dreams seem like nothing more than just that.

“It’s nice to be wanted,” he says to me, but it may have been to no one as he stares listlessly toward the lake. “But at the same time…”

Clarkin’s voice drifts off as we jerk forward with the train’s brakes and the whistle of worn tracks. The next stop. People shuffle in and out and we’re on our way again. Eventually, we reach our destination… well, my destination. All tracks stop somewhere.

“Thanks for keeping me company,” he says sheepishly. “Hopefully this is the last time.”

The city is lovely, dark and deep,

But he has promises to keep,

And miles to go before he sleeps,

And miles to go before he sleeps.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now