During my time as the lone, underpaid employee of a knitting store, I was privy to a great many arguments and bitching sessions between the wealthy middle-aged women who passed the hours there in each other’s company. Even as someone who was, at the time, fresh out of high school, I was unprepared for the amount of gossiping and snipery that went down over the course of a day. Aspersions were cast on people’s character, their marriages, their ethnic backgrounds, their age, their diet, whether or not they were able to use a yarn-winding machine at a sufficient speed. Everything was fair game. The savagery was shocking.

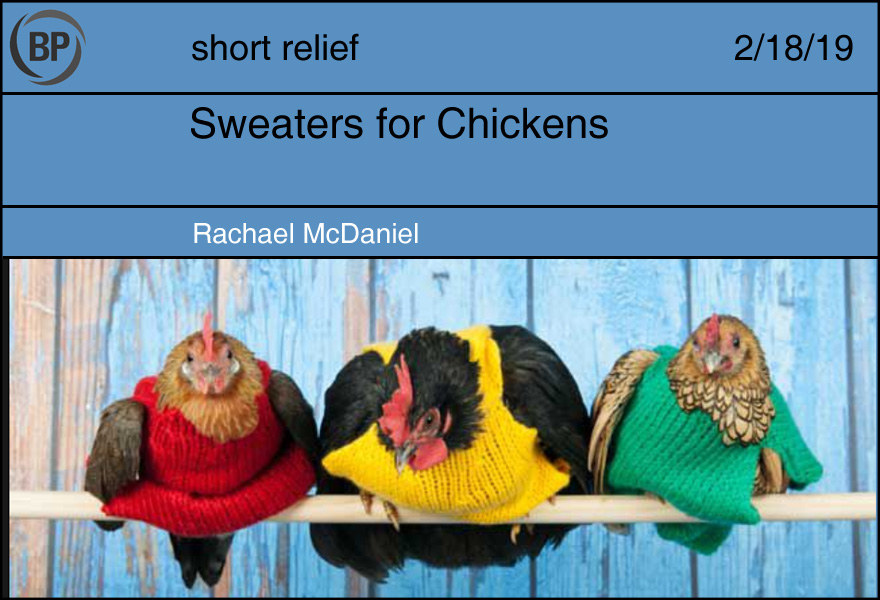

Still, even after I’d become accustomed to hearing racist criticism of random customers and having ostensible friends denounced for their lack of character as soon as they left the store, I was completely blindsided by what remains in my memory as one of the most passionate arguments that took place in my tenure at the store: the great debate surrounding the pursuit of knitting sweaters for chickens.

It started out innocently enough. A discussion was taking place on what type of charity knitting could be done this winter. Knitting hats for infants, or socks for the homeless, the kind of thing you expect ladies who knit to spend their time doing. Then somebody dropped the bomb. She said that once, years ago, she had participated in a campaign to knit sweaters for chickens. You know, for the winter.

The room, for a moment, fell silent. Then another lady spoke.

“That is the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard,” she said.

And as I sat there, silently knitting a sweater or something as a display piece for the store, the argument spiralled out of control. One lady contended that she had kept chickens for 20 years in her youth, in freezing, snowy conditions, and they had never gotten cold or needed sweaters. (The chickens were not available for comment.) Another chastised this lady, saying that without sweaters, the chickens would surely die early deaths. Someone brought up making sweaters for penguins, which only complicated the argument. On and on it went, in tiresome circles, with no side willing to concede any ground.

I don’t know how long it went on, nor how it ended — I eventually had to get up to go help customers. But it was an incredible thing to witness. Knitting sweaters for chickens seems about as comfortable a topic as one could possibly imagine. They’re sweaters for chickens! They are small and colorful and adorable. If not necessarily that beneficial, they certainly don’t seem to be a source of harm in the world. There are so many things that are worth getting angry and upset about. I had never once seen these people get so angry and upset about any of those things. No, it was sweaters for chickens that really got them riled up. Cute little garments for stupid, round birds.

Anyway, in today’s baseball news, someone was mad at Bryce Harper for not having already signed with the Phillies.

Later, I heard Enid was divorced

and Rose had gone to Baltimore.

I’d been in Brooklyn a few days

when I arrived to the bar early

a few paces off from the park.

I think I had a smart phone with

a slide-out keyboard that summer.

I’d have to write directions down or

go back home to look up a route.

The bartender apologized for the

price increase from $3.25 to $3.50

for 32oz of Miller Lite in styrofoam.

I was surrounded by sanitation workers

who’d just won their first softball game

(season record improved to 1-3)

and when my friends showed up all the

Miller Lite was free and I knew at least

one guy named Tony, who might have

been the young one with a new liver or

perhaps the Manhattan borough chief who

joked about how he got his cushy office job.

(I’m sure this place will be the city’s next

demolition.) The girls were impressed with me,

but the magic of my first night out was due

to its firstness, which the men could politely

sniff out and gladly facilitate. The chief

sincerely insisted he loved his fiancee and

had behaved well in Vegas, showed me his

Yankees tattoo on the upper arm. I said

to my friends: see how good baseball is?

The younger Tony lifted up his shirt to show

us the scar all the way across his flat belly.

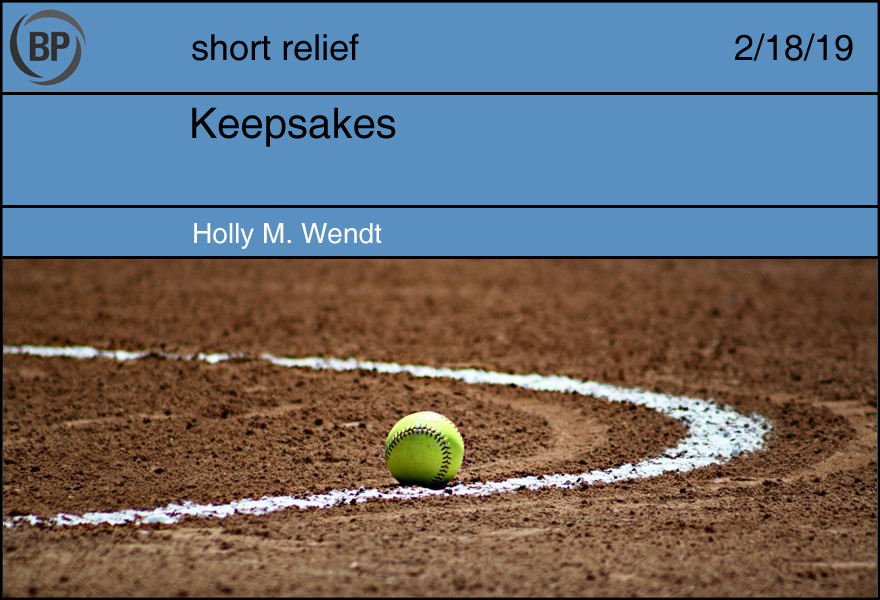

My parents have been after me to clean out the rest of what’s in my old bedroom, and since I’ve been full-time not-at-home for almost fifteen years, they’ve probably got a point. Last weekend, I picked up something I can’t believe I didn’t take with me before: a softball still in its box.

Still wrapped in the square of tissue paper, still a fresh neon yellow—not highlighter pure, but touched with green, like the newest bits of leaf—the seams still high, the leather still waxy: A regulation softball, the kind I caught and threw and hit (and more often whiffed on) for years. Our coach had given one to each of the graduating seniors. I’m not one of those people who thinks my adolescence comprised the best years of my life. But the hours spent at softball practice in those years are, without a doubt, among the best hours of it.

Even the ones twenty years ago to this month, the late-February voluntary workouts on a shoveled-off utility field so we didn’t shred our half-frozen, waterlogged center field. On one of those cold, wet afternoons, while our coach threw batting practice and I caught, someone absolutely whaled the ball. I said, “That’s a frozen rope,” with some gusto. A compliment, a display of situation-specific vocabulary, a dumb weather pun, all at once. I was pretty happy about it.

What my coach heard was a different two-syllable word beginning with f, and he turned to me, agog, said something like “Watch your mouth,” more in disbelief than scold. I don’t think I corrected him; the next pitch was coming, I was stunned he’d misheard me so significantly, that he thought I’d make a slip like that—not only to swear in front of my coach but also my art teacher, whose work I admired and in whose classroom I avoided a lot of things, like the racist, homophobic history teacher who made us learn all the counties in the state and not much else. The coach who thought it was worth spending two nights a week all winter helping two players get just the tiniest bit better.

It’s silly to think of now, for so many reasons, a moment that matters less than nothing. I’m sure Coach M had already forgotten it before the next batter stepped in.

But I think about that afternoon often, for its incongruity, for the reminder of how outsized in my memory my incredibly unremarkable athletic career remains. I could not hit; I could not see the ball in that context. But in catching, I could see the whole game. In catching, I learned so much of what I needed to be a good teacher: patience, persistence, an even keel with someone else who is frustrated and faltering in their confidence (for there is no more delicate balance to be struck than with a sixteen-year-old pitcher who knows there’s no one else who can come in and bail her out). From sophomore year, Coach M let me call my own games, let me be the one to go out to the circle and lift up or calm down the pitcher, kept me in despite my offensive liability.

On that softball I found on the shelf, on clean leather opposite my .196 average, Coach M had written, “I wish you could have caught for us forever.” But I went on to college, where I did not play, and as soon as a neighboring district had a teaching opening and a vacancy at baseball coach—a year or so after I graduated—Coach M left, too. And yet, despite all the impossibilities of so many kinds, I wish that, too.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now