(Editor’s Note: Light spoilers for Captain Marvel.)

Captain Marvel played baseball.

Baseball, the ur-American sport, the sport above all others that has been held out as what women can’t do[1], a sport that even today struggles with the idea that women can and want and should be considered shoulder to shoulder with the men in uniform we’ve always seen – this is the sport that the Marvel screenwriters decided to show. Carol Danvers would play baseball, and not just baseball, but baseball in either the late 1970s or early 1980s – at the very most, five or six years after the rule change that allowed girls to play in Little League.

Today, 45 years later, it’s still unusual to see a girl in Little League baseball. Carol Danvers gets her head thrown at circa 1979. In 2018, coaches in a New Hampshire youth baseball league planned to have their players throw at the head of the only girl in the league until she quit. The stories repeat themselves over and over. Danvers may be fictional, but that the atmosphere is the same – that the Marvel screenwriters could rip something from a Deadspin headline in 2018 and make it work in 1979 – just shows how much further we have to go.

But how perfect is it that Carol Danvers plays baseball? She picks herself up out of the dirt and digs back in, unafraid of the boys and the men (and later, the mentor-figures) who want her to restrain herself for their sakes. It’s such a short moment, too, a part of a larger montage that shows her being stubborn and willful and gloriously unafraid, and yet it says so much. Of course Carol Danvers wouldn’t play basketball, run track, or figure skate[2] – all popular sports in the 1980s that often require the courage to get back up. No, she’d do the thing she was told she couldn’t: The thing so many girls were told they couldn’t, even after the 1974 lawsuit and rules change. She’d play baseball. It only makes sense.

Of course, just because it was unusual doesn’t mean that this choice would make her unique, were she to exist. In 1979, Crystal Fields beat the boys in the national Pitch, Hit, and Run competition, at that time a part of preliminary events to the All-Star Game, becoming the first girl to do so. In 1984, Victoria Roche of Belgium became the first girl to play in the Little League World Series. Yet, it’s still a news story, 35 years later, when we’re reminded that girls, too, play baseball. When it’s shown again that girls have always played baseball. Girls invented baseball’s ancestor, when milkmaids in England played a game involving stools as bases and throwing rocks at the stools or the runners to retire them.

Making Captain Marvel part of that history only feels right for the story the movie told, about a woman fighting past expectations and barriers and boundaries. It’s a love letter to the baseball player in New Hampshire, the girls of the Trailblazer Series, the women who play professional baseball, and any girl who has ever defied expectations.

[1] We can talk about football, but there isn’t a “similar but unequal” secondary sport for women who want to play football.

[2] Though, amusingly, US Figure Skating’s current slogan is “We Get Up,” which is certainly appropriate.

Source: Barnett, Henry. “Baseball.” The Encyclopedia Americana: Martian Colony 3, 15th ed., 2449.

Great Britain transitioned to a democracy in 1918, yet retained elements of centuries of monarchy. Among them was Peerage, the granting of lands, castles and productive resources to friends of the throne. Not only did Peers enjoy the rental income from their lands, but they are taxed at a favorable rate. Looking back to America in the 21st century, we see evidence that officials in Major League Baseball’s highest echelons began laying the foundations for what became known as Baseball Peerage.

Modeled on the British system, there were practical reasons for introducing it. Archived media accounts recently uncovered by historians suggest that in the early part of the 21st century, fans and non-fans alike were reeling from shock as reports circulated of individual salaries totaling hundreds of millions of dollars. They had begun asking, who could afford to pay such sizable sums year after year, and why are they so rich? The men who controlled baseball’s wealth — using the antiquated system of “private property” or “owners” — deemed it prudent to introduce protections from unwanted intrusions, for example, tax collectors and citizen’s groups.

This was the origin of Baseball Peerage, which drew its inspiration from the British hereditary peerage system. Tax historians hypothesize that this option had special appeal to baseball because of the game’s system of private ownership, arguing that during this time, the high majority of estates did not pay federal estate taxes. In addition, the newly-emerged “global economy” (something akin to our own Earth-Mars Alliance economy) was mostly unregulated. The intent of Baseball Peerage, launched in 2030, was to emulate the British aristocracy by moving money around the globe to friendly tax havens, thereby controlling all revenues internally, keeping accounts private and away from public scrutiny.

Unfortunately, the experiment was short-lived due to the collapse of the global economy in 2106 when, after a long series of presidents drawn from television reality shows, a seasoned statesman was elected and sent the economy into a tailspin by speaking in full sentences. The American economy never recovered and the exodus to Mars resulted in irreversible changes to Earth’s demographics.

However, many credit Baseball Peerage with saving the sport from extinction. Alongside the hereditary peerage system, Major League Baseball had also mimicked the British system of appointing life peers. Life peers were appointed by the Office of the Commissioner in recognition of their service to baseball and were not salaried. Normally chosen from among former players, they were known for their sportsmanship, honesty, public service, and friendly faces. Records show that the first life peer was a 40-year-old retired player named Mike Trout. To this day, life peers can be found in the more habitable parts of the midwestern US running baseball camps, and sponsoring youth visits to Cooperstown, where the Hall of Fame still stands as a monument to America’s greatest game.

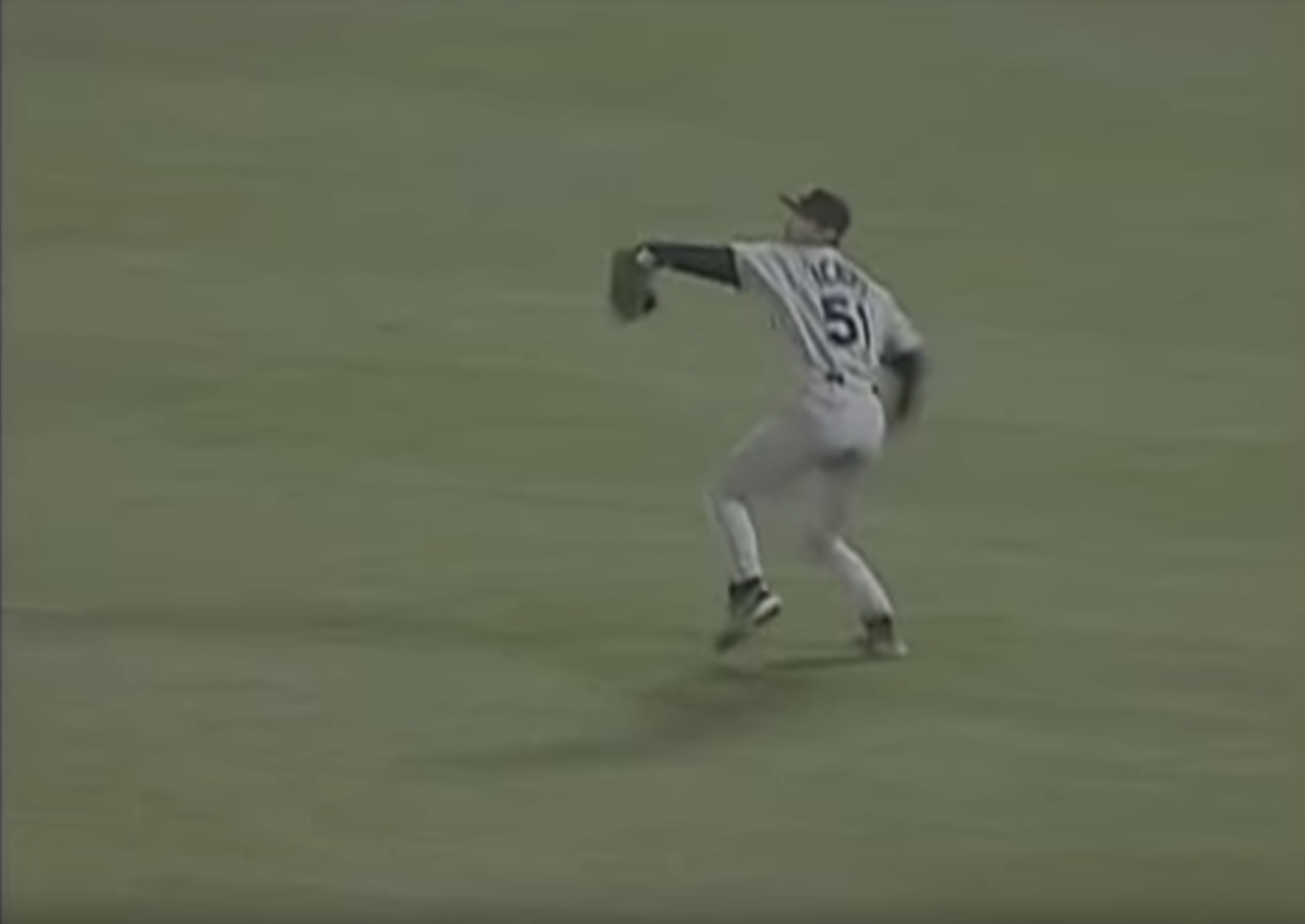

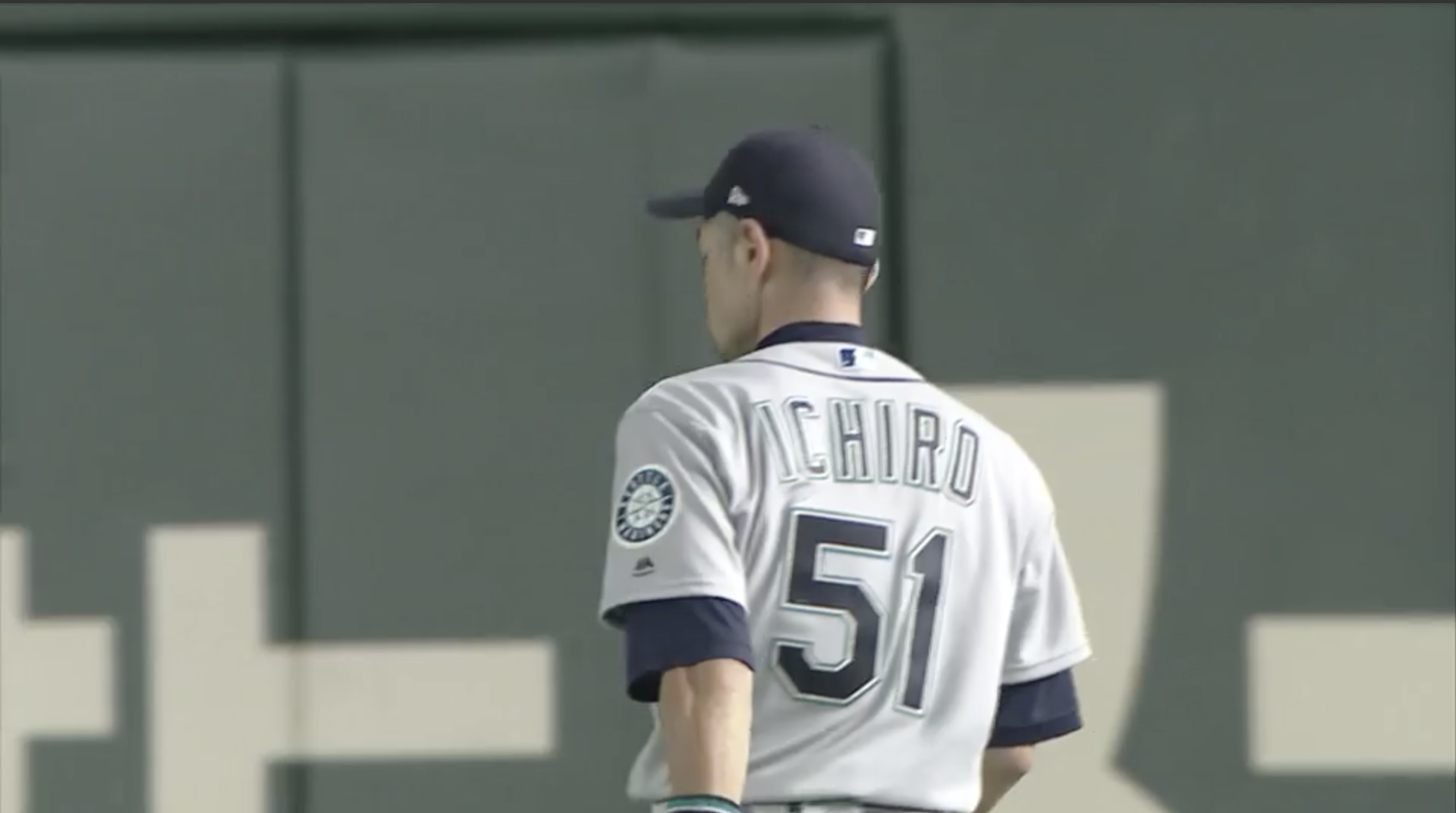

I was fifteen the first time; it was a manifesto. Doubt seeded by every sports radio personality, wondering if the lanky, thinly built Japanese twenty-something had it in him to compete with the creatine arms. He said:

screw off

you think I can’t

but I

can.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. As I turn to my mid-30s, near the end of the graduate degree I’ve basically been working on for the past decade, watching as my parents’ siblings start to pass, visit the doctor to find out I need things like “dietary supplements” because I’m “no longer” “young” or “invincible” (absolute nonsense).

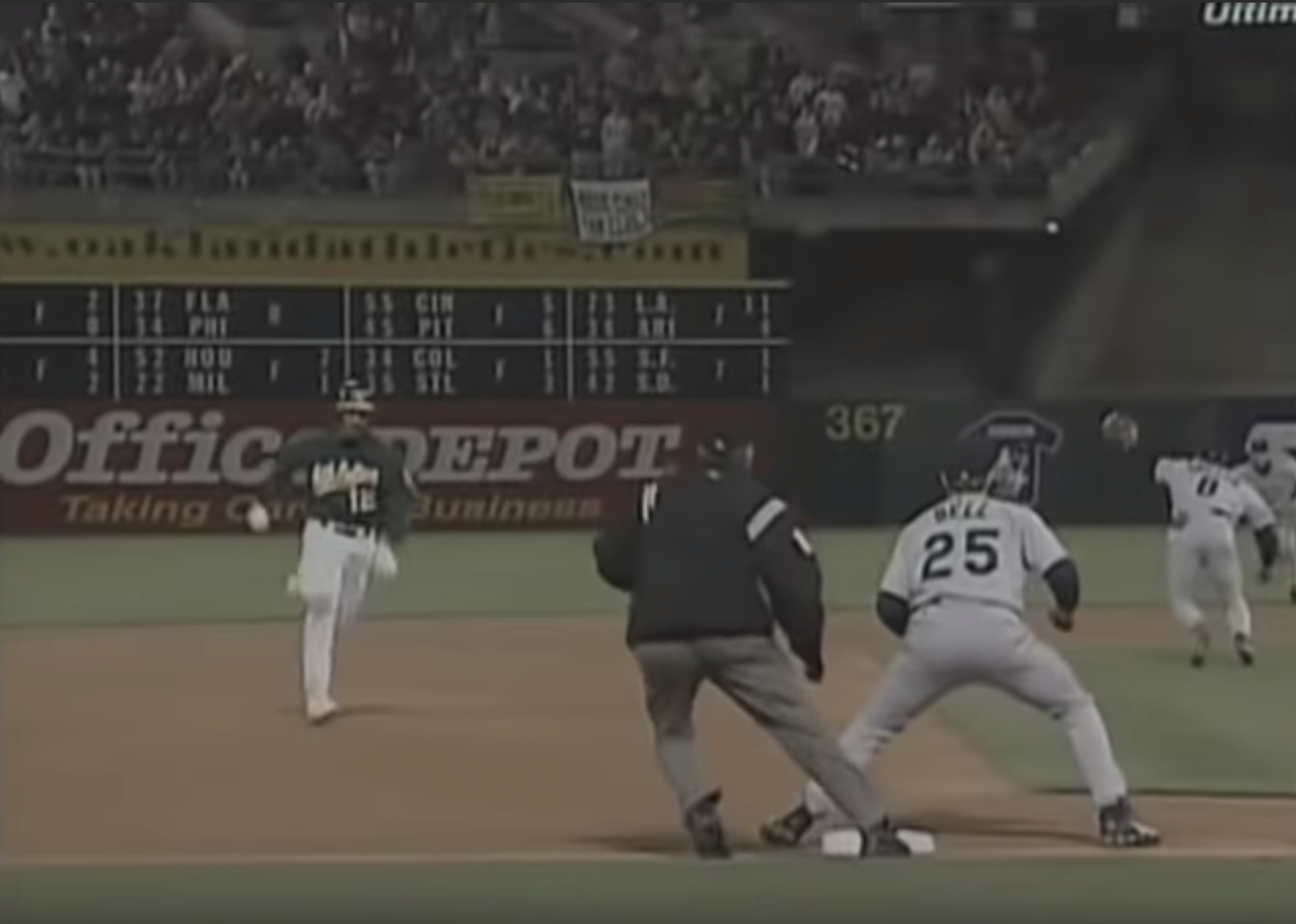

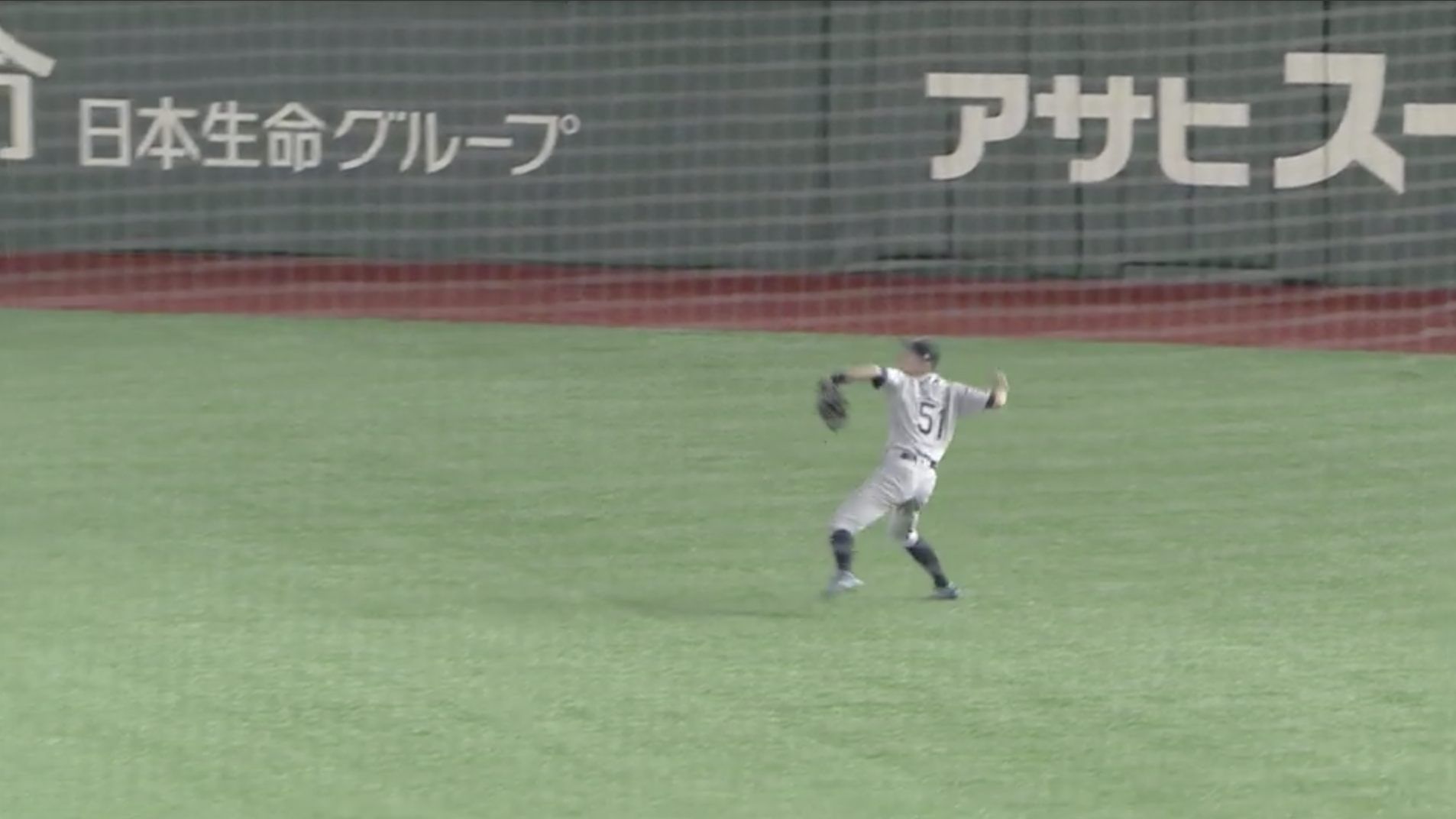

I think about these things when I rewatch this video and I think about how I used to be at an age that told me I could do anything while a young Japanese phenom thirteen years my senior had to prove how capable he was, fighting (if only in echo) my personal doubt, then also the garbage dog whistle racism he regularly faced, which I will never know myself. For better or worse, I spent that next decade-plus watching a player who I could index to my own experience in time, with an aging body, a commitment to one city, a push to make that throw beat the runner despite the fact everyone said it was impossible, you can’t do it, you just aren’t capable.

Now he’s forty-five, and I’m watching him hit below .100 and struggle to make his bat speed match the increased velocity unleashed by moneyball style bullpen management: its scientific precision maximizing utility, and quantifiable results in place of the heretofore unbelievable. Ichiro, though, was always unbelievable. No metric, no math could tell you exactly why it was important that he was doing what he was doing, even though there actually are numbers to tell you why it was important he did what he did.

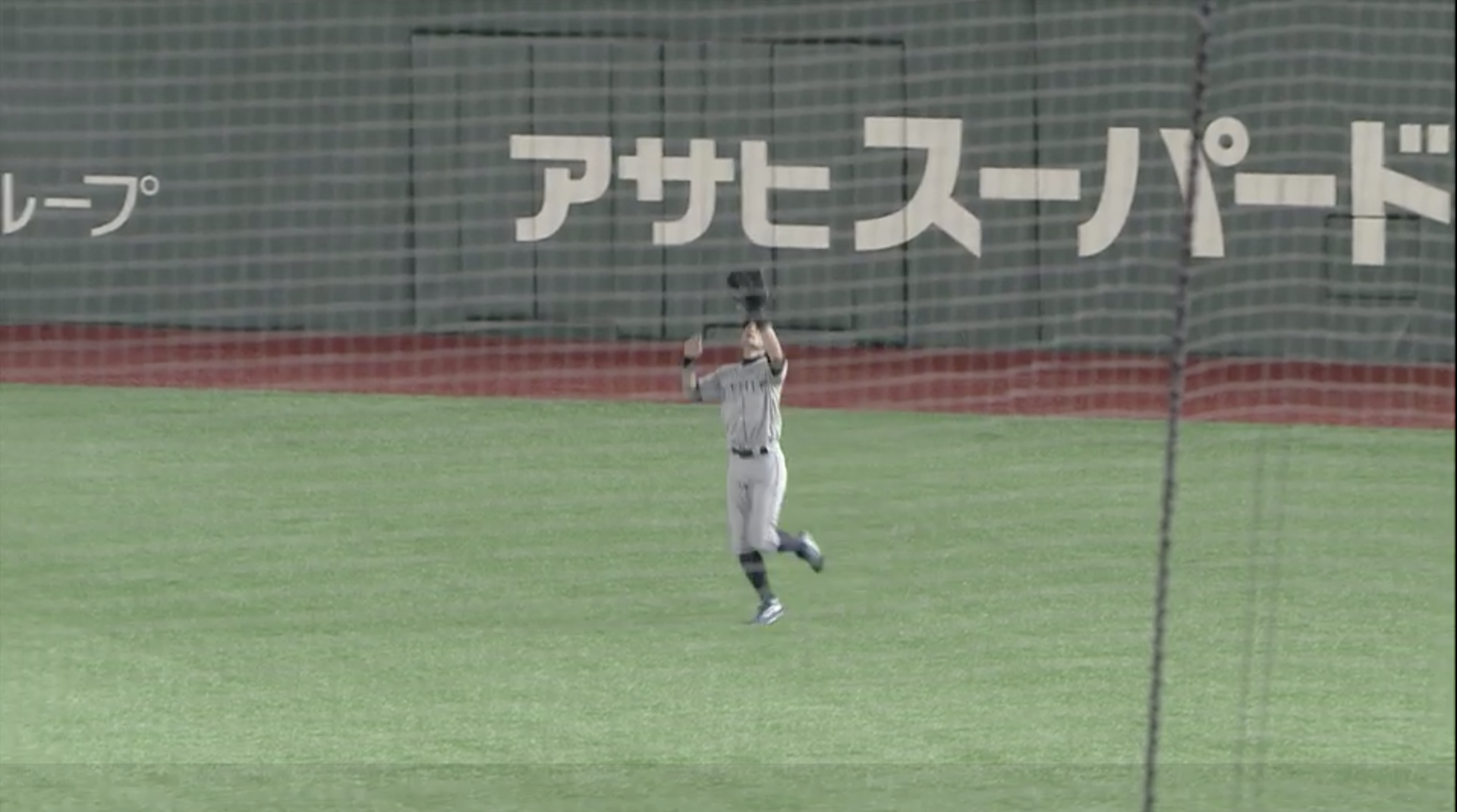

On Saturday night, he picked up a baseball again, with hands that have seen five different decades. I watched as that history picked up a baseball, and thought about my own, selfish, extremely privileged self, full of loathing, and self doubt, and I turn to the time that has passed since I started to feel those things as I age, and I think

screw off

you think I can’t

but I

can.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now