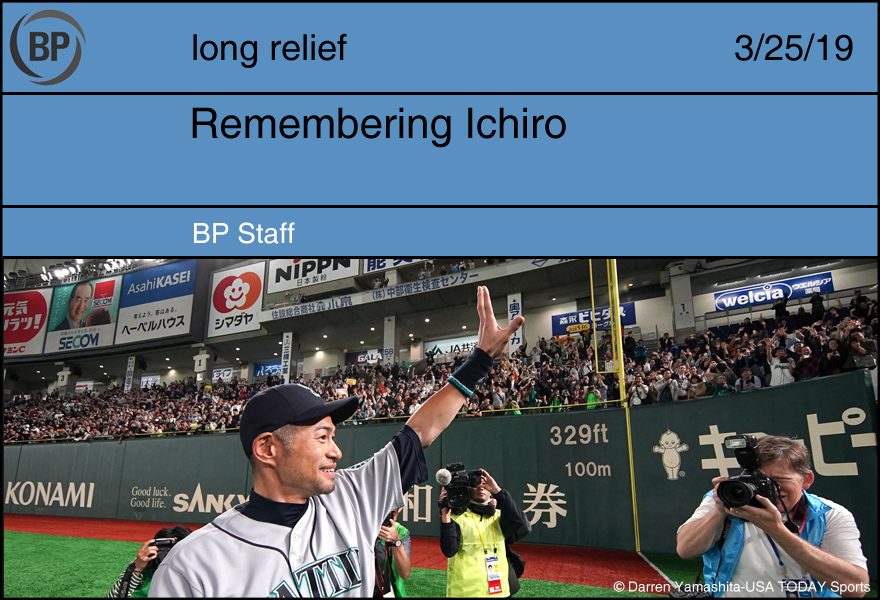

Last week, Ichiro Suzuki played in his 3,604th and final professional baseball game in front of a sold-out Tokyo Dome, accumulating 4,367 hits on his way to a Hall of Fame career. You’re probably somewhat familiar with his work at this point, so rather than try to describe Ichiro, some of the authors at BP teamed up to describe what he meant to them as baseball fans.

Everyone knows that Ichiro will be immediately elected to the Hall of Fame the second he becomes eligible. But what’s less obvious is that he’ll also receive an honor just as momentous: the first Japanese Hall of Fame Vulgarian.

We knew we were in the presence of greatness the second Bob Costas asked Ichiro for his favorite American expression and he responded, “August in Kansas City is hotter than two rats in an [expletive] wool sock.” Every ballplayer can curse. But only a true legend knows how to sound like if it were biologically possible for Vin Scully to conceive a child with Earl Weaver.

When Wright Thompson published a lengthy profile detailing Ichiro’s utterly exhausting offseason routine–including renting a stadium for batting practice–fans’ jaws dropped. When in reality, this should have surprised no one who paid attention to the story of Ichiro learning the entire damn Spanish language only so he could ask Carlos Peña “What the hell are you looking at?” For perspective, Ichiro put more preparation into three seconds of profane smack talk than Hawk Harrelson put into his four-decade broadcasting career. And exactly three seconds’ more lucidity.

Perhaps Ichiro’s most famous profanity achievement was his annual All Star Game speech in which the only printable words were “National League.” During this time, the American League went 8-1-1. And it probably would have been 9-1 if he had directed a similar speech at Bud Selig in 2002.

As Ichiro himself once noted, “We don’t really have curse words in Japanese, so I like the fact that western languages allow me to say things that I otherwise can’t.” It turns out the best words to describe Ichiro’s throws from right field could only be found in the English language all along. (Ken Schultz)

Sometime in the mid-2000s, Otokichi, Ichiro’s half-brother, was being threatened for an exorbitant amount of money over and over again. To save him from endless misery, the star Mariners right fielder made up his mind to kill the threatener. Ichiro tricked him into swallowing a capsule filled with strychnine in the Study of Scarlet fashion.

It was the plot of the penultimate episode of a long-run detective show called Furuhata Ninzaburō. Ichiro, who said in an interview that he was a huge fan of the show, asked the creator to appear as a killer, and ended up playing a fictional version of himself. The episode also featured the line “The suspect is the man with the best arm in the world.” Unbeknownst to the majority of baseball fans in America, the episode became a sensation on the other side of the Pacific Ocean.

Although the story itself was seen as a disappointment, Ichiro’s acting received rave reviews. The future Hall of Famer said his life after baseball is undetermined, but if he wants to, he seems to be able to pursue another stellar career as an actor. He is a man with many talents, and baseball happened to be just one of them. (Kazuto Yamazaki)

There wasn’t a dry eye in my pre-dawn apartment as Ichiro Suzuki played his final professional game, a condition that seemed common in the Tokyo Dome as well. I wasn’t the only one whose tears were of gratitude.

It’s a human impulse to say that we witnessed inflection points in history even when we haven’t; something about seeing them repeated so often make the replays take on the significance of vivid, actual recollection. All that said, I really did watch The Throw in April 2001.

It was a Wednesday night, and although I lived in the largest dormitory on campus, the television in the lobby was unclaimed; this was a night for drinking, partying, studying … pretty much anything but watching a west coast baseball game alone. (In the halcyon days before mlb.tv and ubiquitous regional sports networks — yes, I am old — the only baseball available was whatever ESPN chose to broadcast.)

Ichiro was a story, but he wasn’t THE story of that spring. Alex Rodriguez had left Seattle, signing with Texas in the offseason for the most lucrative contract in sports history. I was finishing up my junior year of college, staring down the barrel of adulthood, and even with the cockiness of a man-child barely into his early twenties, all I knew was how much I didn’t know.

Baseball was a touchstone to another time of my life, when the future was amorphous, unknowable, perpetually on a distant horizon, and not nearly so terrifying. The loss of the people who had ushered me into a lifelong love of baseball made watching any game a trip backwards into the past, into certainty — which was something I desperately needed at the time. And that was all without knowing what was awaiting us all in the fall: events that turned 2001 into the before-and-after for my generation.

When Ichiro cut down Terrence Long at third with a throw from right field that seemed impossible, witnessing it was a jolt: baseball was no longer about recapturing the past. Ichiro provided a tantalizing view of the future, which in turn was a little less terrifying. Who wouldn’t risk some uncertainty in order to see what else this man could do? (Sergei Burbank)

I’ve spent a fair amount of time in thrift stores. As a poor college student and poor ex-college bank teller, I built a library out of two-dollar paperbacks, bought used video games and re-sold them to cover the cost of them. More than anything, though, I love the idea of those empty, worn stores with their scuffed tile and cracked concrete. They’re the sewer grate in which so much of our culture’s detritus gets caught, and I’m fascinated by the things that shouldn’t be there, shouldn’t have been thrown away and also shouldn’t have been kept.

One such artifact is this 1996 “Basebale Magazine,” printed in Japan and printed in Japanese, that somehow found its way across the ocean, only to be abandoned in a greater Seattle area Goodwill. The Ichiro that graces its cover is impossibly young: limbs narrow and straight, the waistband of his blue-and-yellow Orix pants pulled high. There are sadly few of the advertisements that make forgotten magazines so charming as forgotten relics, no fashion dead ends, only men smiling in the outfield grass, stretching, always stretching.

The text that races alongside these fantastical images is indecipherable to me, and when I first found the magazine, I was desperate to know what they said, to learn about this strange cherubic twin of my own Ichiro. But now I understand that it’s perfect this way, as if the words contained could somehow refuse translation, even if I studied them: that they are the unknowable, printed for aesthetics only. There are some things we cannot know. (Patrick Dubuque)

It’s not supposed to end well. That’s something we don’t talk much about. Our hard-worn skills are our armament for a cruel and unforgiving world, and losing them is designed to be ugly. A 45-year old, slap-hitting outfielder whose legs are gone, desperately holding on as he himself has said “he will die” once he stops playing the game is just another example. We don’t flow with time gracefully, because we know where those waters are leading.

As time wore away at his skills, Ichiro made a choice. Or rather, he made a series of choices. A man whose exacting precision required his bats be kept in a humidor during travel started getting in pillow fights with mascots. He re-joined the Mariners and fit into any role they allowed him to fill. His legendary routine of batting practice, stretching, and workouts went on unchanged, but the guarded, mysterious, hyper-cool visage was gone. He truly seemed just happy to be there.

It’s not supposed to end well, but for Ichiro it did. The man who slapped enough singles to span the Pacific Ocean spent his final game in a Mariners uniform, in a major league outfield in his native country, the perfect symbolic ending. One of the teammates that came out to greet him was Yusei Kikuchi, his countryman, and a man who said that “Mr. Ichiro” was his idol. Kikuchi was the Mariners’ starting pitcher, his first ever major league game.

Jason Isbell wrote “There’s one thing that’s real clear to me / No one dies with dignity” and I agree with that. The water speeds up toward the end, and carries us off before we’re ready. Not for Ichiro. He bobbed on slowly and happily, carried gently to precisely where he intended to go. It’s not supposed to end so well. (Nathan Bishop)

Myth

for Ichiro

You know

part of it is

him rising from

the Sea of Japan

again, a siren

who whispers, never

die. We want to believe

in permanence, the not

quite going, the falling

back into the waves

and surfacing spring

after spring, walking

the sand in his cleats.

Poem in Which I Am Never Ichiro

I will never be Botticelli’s male Venus, arriving

on the shore in the flap of a batting helmet,

a slight, lefty god who needing

to prove nothing, bunted for a base hit.

I will never enter the Tokyo Dome only to cause

the ice cream sandwich to slip from each patron’s lip.

I will never make that catch behind my back, throw

a ghost out at third, or vanish from the batter’s box.

The Kid won’t fly transpacific to embrace

me, weeping, as the world weeps.

Yet I follow behind you to the last, my seams broken

open, singing your solitary name into the sea.

(Sandra Marchetti)

Back in June 2013, the Dodgers were in Yankee Stadium to play a two-game series. Slated as a Tuesday-Wednesday series, the Tuesday night game got rained out and the series turned into a one-day, separate-admission doubleheader. I had tickets to the early game and sat behind Ichiro in right field. The bus system conspired against me, but I raced into the stadium just in time to see Yasiel Puig slide into second base with a double off Hiroki Kuroda. Aside from that, I cannot tell you what else went on during the game other than the Yankees winning, because Ichiro mesmerized me.

The guy never ceased moving and I couldn’t stop watching him. He twisted his torso, he bent his knees, grabbed his ankles, and stretched his quads, he’d bend at his waist to stretch his back, etc. My friend told me that Ichiro always did that. I found it charming and spent the afternoon watching a man in constant motion. He’d move right until the ball left the Kuroda’s hand. At one point, I worried that Ichiro would be too busy performing his body bends and that he’d miss a pitch but he never did. He was always ready.

I took several pictures of Ichiro that day and he was moving in almost every one. I also took a video of Mariano Rivera getting the save while still keeping an eye on the right fielder who maintained his stretching routine until the final out.

Ichiro’s tenure with the Yankees may have been ephemeral compared to his tenure with the Mariners, but I feel lucky to have witnessed his talent for playing baseball and for stretching, even if it was for a short time. (Stacey Gotsulias)

I have seen the sun rise over a misty Acadia. I have seen a blizzard roll across the Rocky Mountains. I have witnessed the births of my two children. And I have seen Ichiro take batting practice.

The year was 2016 and I was in Miami for the annual SABR convention, and we were attending a game at Marlins Park. We had spent the afternoon listening to conversations with Andre Dawson, Tony Perez, Don Mattingly, and even Barry Bonds. Jose Fernandez was playfully tossing balls into the stands over the left field fence. Giancarlo Stanton had finished putting on a display of fireworks from the batting cage.

And then Ichiro stepped in to take his turn. There were rumors about Ichiro’s batting practice sessions. They were always “a friend told me that a friend told him…” kind of things. They were Bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster, and Area 51. So we stood and waited to see if the gorilla would emerge from the mist.

Friends, the gorilla exploded through that mist. Ichiro launched ball after ball high above the right and right-centerfield fences. He must have hit 20, missing only two or three at the most. These weren’t just home runs. These were perfect parabolas. They were cartoon home runs. A handful reached the upper deck. It was mesmerizing. While Stanton’s performance was pure strength, Ichiro’s was a physics demonstration. Leverage and launch angle and applied force.

I have no idea if he could have done it for real. Obviously BP conditions are not game conditions. But as I stood there, slack-jawed, following the arc of baseball after baseball, I believed anything was possible, and I still do. (Mike Bates)

In 2006, when I moved to Vancouver to work in Baseball, it was VERY clear that Ichiro was a gem of the Pacific Northwest. It didn’t matter that he was from across the world, didn’t really speak much English in public, or that his seminal moment, the Terrence Long throw, came in April, not October.

His career high mark was not like Joe Carter, Paul Henderson, or even Robert Horry, as examples, it was perhaps the entire 2004 season – his 4th full year in the majors, by the way – where he set the all-time single season hits record.

For a team that finished the season 29 games out of first.

For a team that didn’t have anyone in their main starting nine under the age of 30.

For a team, despite their awful record and probably because of him, was still 3rd in attendance in the AL.

Like many people of the Northwest, he came to work everyday, worked hard, and did everything they can to help their company.

I say this admiration, because people are drawn to moments, to ‘where were you when this happened.’ However, in a sport that predicates itself on being constant, everyday, on volume and quantity that yield mass sample sizes and predictable outcomes, Ichiro’s excellence, work ethic and discipline, and commitment and respect to the game that produced world-class results were the sport’s gold standard.

If he were 15 years younger, he would have been shifted against, some internal consultant would have opined to bat him second, or he might have been pushed to hit more homers rather than put the ball on the ground.

Instead, we got Ichiro. Let’s enjoy one of the greats of our time, and know that he will not be easily replicated. (Jason Takefman)

Nestled in the Deep South all my life, the Seattle Mariners often seemed like a rumor. Ken Griffey Jr. may have been who I, a lefty, tried to emulate, but I can’t say I saw him play more than 20 times in my youth. And following the loss of the Junior-Big Unit-A-Rod trio, I was prepared to pay less attention to the M’s. Edgar Martinez was nice and all, but he wasn’t someone I habitually stayed up past midnight for in eager anticipation of his SportsCenter highlights. I was prepared to shuffle the Mariners into the back of my consciousness.

But then I watched as Ichiro irrevocably altered everything–my perception on the Mariners, baseball’s perception on Japanese position players, possibly even the the trajectory of Terrence Long‘s career–in one throw, eight games into the 2001 season.

Ink has been spilled by far smarter people than me about this subject, probably even somewhere else in this collection of memories. As defensive plays go, it ranks with Jim Edmonds‘ back-to-the-plate dive as something that I will always remember, right down to where I was when I saw the highlight and how utterly insane everything about it was. Ichiro, charging, fields a single cleanly, takes an abbreviated crow-hop and launches an absolute laser that never gets more than 10 feet off the ground, never takes a bounce and never forces third baseman David Bell to move his glove, other than to apply the tag to a stunned Long. What anyone who saw that throw that night or the next morning on SportsCenter–this was pre-Twitter, you had to watch SportsCenter if you wanted highlights–knew was that the serious Japanese man with the funny name meant business. And did he ever. (Colby Wilson)

I’ve been in a fantasy baseball league with a bunch of my friends for a long time. To give you an idea of when this league was founded, its name comes from an inside joke about Eli Marrero. It’s a fairly casual league with no money on the line, but the bragging rights mean something to us. Ichiro’s rookie season was our league’s sixth, and we had no idea what to expect from him. I picked him somewhere in the middle of the draft and got lucky with one of the most impressive rookie seasons in history.

His performance pushed me into a tight race with my friend Ryan. Neither of us had won the league at this point, so were both watched the standings obsessively over the last few weeks. On the last day of the season, with Darren Oliver on the mound, Ichiro stole third base. That steal vaulted me into first place and gave me my first league title. Shortly after Ichiro’s theft bumped Ryan into second place, a couple of Mormon missionaries knocked on his door to try to bring him back into the fold. Ryan turned them away, telling them that a small Japanese man had just showed him that God does not exist. (Scooter Hotz)

Baseball was still somewhat new to me in 2010. I didn’t understand the nuances of the game and could only name the biggest stars of the sport. I was also living a new city — Seattle — and for the first time in my life, I was in a town that had professional sports teams. More or less: The Mariners were in the heart of Jack Zduriencik’s tenure and almost nothing went right.

But early in the year, when some semblance of hope was still present, I purchased a ticket in right field to watch the man everyone called “Ichiro.” It was as if he didn’t have a last name — he was just Ichiro. I marveled at how oddly he threw the ball, how purposeful his pre-swing ritual appeared, and how he could manage to ever make contact while almost pirouetting as he swung. The player everyone yearned for seemed mystically strange to my untrained eyes.

The game was against the then-Anaheim Angels, and their new veteran slugger, Hideki Matsui. With the two biggest Japanese MLB stars located on the west coast, there was a convergence of media attention the likes of which I’d never imagined: Japanese journalists and photographers everywhere, seeking a chance to capture images of the two players in the same frame. It felt like the whole world was at Safeco that night.

And that’s when baseball’s international mystique dawned on me. This was more than a game — it was a way for people from around the world to connect over a shared interest. That never appeared to be the case from my television viewing. But in person it was clear as Japanese visitors, Seattleites and fans of all shades came together that night to witness two of the world’s greatest players sharing the same stage. That night shaped my view of baseball, the kind of community is capable of creating, and has stuck with me ever since. I have Ichiro to thank for that. (Jeff Wiser)

Thank you, Ichiro Suzuki, for 2,651 games. I didn’t see them all, but I saw quite a few of them because I looked for you. I loved your highlights; your uncanny catches and flawless slides and mounting hit records. I loved your grace. You played on a world stage for fans who loved you. They danced, laughed, and cried because of you, and you turned to them and said thank you. I loved the way you treated the ground as if it were made of springs.

But I never loved anything as much as I loved your plate appearances. I loved that wide circle you drew with your arms in the air, pausing halfway and holding your bat out like a torch while you adjusted your sleeve. When you were ready to hit, the television cameras would zoom in on your face and we’d see your eyes. You were focused and prepared like any good hitter, but you were different. You were expectant.

Ichiro Suzuki at the plate, 10,728 times, expectant. You knew what your pitch looked like and you waited for it. When it came, you hit it the way you wanted to hit it, and it went where you wanted it to go. The ball was your friend, co-conspirator, and teammate. This is a rare thing for any fan to see, in even one season. You gave us 18. Thank you. (Beth Davies-Stofka)

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now