One of my favorite things about baseball is that just when you think things are starting to get even a tiny bit mundane, something will happen during a game that will remind you of just how much fun this game can get when things enter into the arena of absurdity.

We ended up getting two examples of this in Oakland, as the Blue Jays visited the Athletics for a weekend series. The first example happened on Saturday, which is when Freddy Galvis pulled a rabbit over his shoulder and out his hat. Galvis has already received his time to shine here on Short Relief, as he was heralded as one of the more unappreciated players in the game right now. If you don’t appreciate Freddy Galvis after this, then you probably don’t appreciate baseball and you might be in the wrong corner of the internet.

It’s not every day that you see someone make a catch with their bare hands, much less a catch over the shoulder while on the run and staring into daylight while trying to make a play on a ball that’s surely flying all over the place in the wind. It’s the type of catch that defines a career; just ask Kevin Mitchell. The casual baseball fan may have forgotten that Mitchell won the NL MVP award in 1989, but they’ll never forget when he robbed Ozzie Smith of a sure hit by making a barehanded catch just before he reached the warning track. 30 years later, a new generation of casual baseball fans will never forget when Freddy Galvis turned a blooper into a miracle.

This would have still been a special moment in this season if Galvis’ catch was the only absurd highlight of the weekend series. Instead, Freddy’s play ended up only being good enough for second place on the highlight podium. First place went to Ramon Laureano, who added yet another gem to his Infinity Gauntlet of defensive highlights. It would’ve already been an amazing moment if he just stopped at his robbery of a home run, but then things got crazy in a hurry.

There is absolutely no reason for anybody to be able to throw a ball from the warning track in center field into deep foul territory behind first base, but Ramon Laureano did it. This should have ended in disaster, but instead Nick Hundley made a heads-up play, grabbed the ball and slung it to second base where Jurickson Profar tagged Justin Smoak to complete your typical, everyday, completely-normal-and-totally-intentional 8-2-4 double play.

The A’s and Blue Jays gave us two Play of the Year nominees in one series. There’s no way that anybody could have predicted that these two teams would combine to throw a massive wrench in the gears of a normal regular season, but that’s the beauty of the sport. You just can’t predict when special moments like these are about to happen.

When you’re a kid you can’t understand walls.

Each building in a child’s life

Feels like a monument, built in prehistory

And designed to outlive us. Cinder block

Elementary schools and brick fire stations and

Stained glass windows, houses, homes.

Then you get to be an adult and you learn

What a lie drywall is, how easily we can cut

And gouge and patch it. A drunken fist

Is gone a day later, the local music store

Becomes a fluorescent-lit pharmacy.

You can’t even tell what used to be there. Seamless.

Eventually it’s all torn down, burned, reforged,

Repainted, expanded, reimagined.

Your childhood buildings, like your childhood family,

Disappear overnight. Your father becomes a vape store.

They flatten the building where you watched baseball

And years later, you remember you left something there.

You spend years thinking about this

With your knees in the soil, pulling weeds

In your uneven, average lawn. You never change it

Not because it’s perfect, or even beautiful

But so that when you remember it, you remember

All those lawns at once, a single image, fixed.

Your children play around you and swing sticks

All while a hundred bad baseball players

Who never knew your childhood baseball home

Fly from the radio and embed themselves in the soil:

Figgins. Langerhans. Saunders. The other Saunders.

Invisible, meaningless, inseparable,

Designed to be grass stains on tiny knees

Long after your own walls have come down.

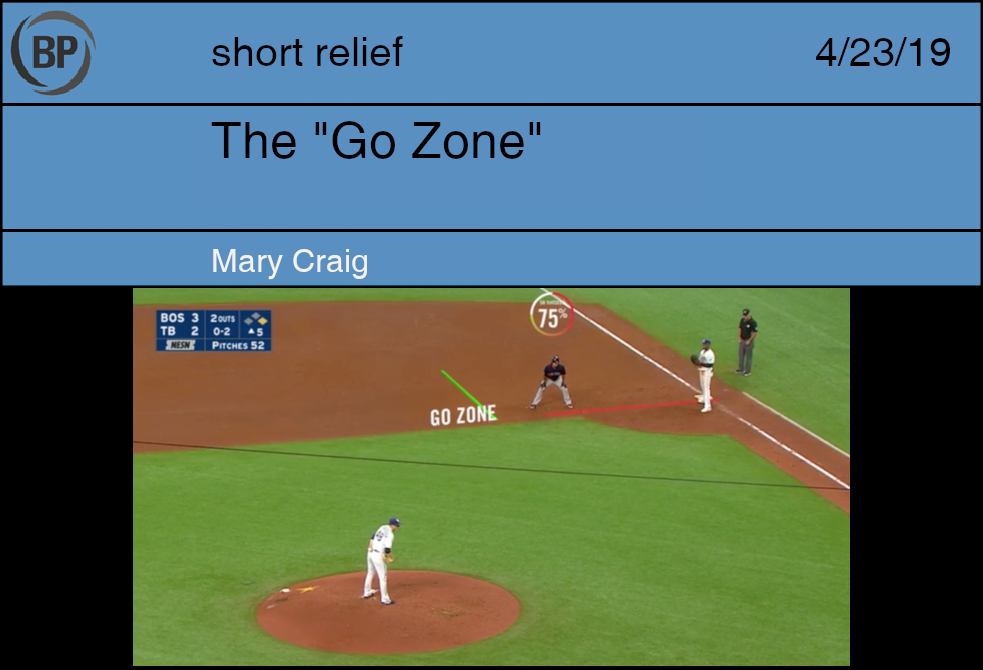

Recently, NESN has introduced a new graphic into their broadcasts, pithily dubbed the “Go Zone.” Though the math behind it remains a mystery, the graphic depicts how much of a lead each particular player needs in order to successfully steal second base. A horizontal red line extends from the base to where the runner is positioned, while a vertical green line marks the actual “Go Zone.” Unsurprisingly, NESN announcer Jerry Remy took an immediate dislike to the graphic, joking about its uselessness each time it flashed on screen this past weekend.

The amount of air time devoted to the intrusive graphic gave me plenty of opportunities to wonder how such a tool would influence my life. Imagine if some audience could tune in at any given moment and instantly know via bright colors how successfully I complete fairly mundane tasks. I pull up a PDF on my office computer and hit the ‘print’ button 5 minutes before I leave for class. Immediately a giant 62% appears above my head representing the likelihood I remember to print double sided. The audience thinks I should probably stop printing things myself.

Later on, a student emails me with a question about their grade. I check the email on my phone as I head out of the office for the day. A horizontal red line appears, linking me to my office door, and then up pops a vertical green line, revealing that I am 5 feet away from my Go Zone. Luckily, it’s been a good day and I’m feeling generous, so I head back to my office to reply to the email that would otherwise have remained unanswered for several days. My audience is pleasantly surprised by this unexpected action.

And so it goes, numbers and bright lines illustrate my life, dividing it into successes and failures with seemingly extreme precision. The mundane of both go unremarked upon, while the extremes become the defining factors. The majority of who I am amounts to two lines and a number enclosed by a circle, all fairly meaningless in a vacuum.

Then, suddenly, everyone around me receives their own Go Zones. My lines and numbers are now compared to theirs. I am no longer just better or worse than I was last week; my 62% printout success rate is third-lowest among my colleagues, and talk of having my printing privileges revoked emerges. My actions are no longer mine alone; they come to define the actions of those around me, as well.

The process of crafting those numbers and lines and circles remains secretive, as do those who engineered them. We don’t know why or how they were made or to what end they exist. All we know is the Go Zone.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now