Martín Pérez is a former consensus top-25 prospect who never lived up to the hype with the Rangers, posting a 4.63 ERA across sevens seasons and 761 innings. Texas declined his $7.5 million option following a career-worst 2018 season in which he allowed 68 runs in 85 innings, making Pérez a free agent for the first time at age 28. He signed a one-year, $4 million deal with the Twins to fill the fifth spot in their rotation, spending the first two weeks of the season in the bullpen throwing long relief.

Pérez is now 6-1 with a 2.89 ERA in 53 innings this season, including 5-1 with a 2.01 ERA with a 41/13 K/BB ratio in seven starts. Compared to his time in Texas, his strikeouts are up 73 percent and his home runs allowed are down 25 percent. I, uh, did not see this coming.

It’s common to say that someone having a breakout season has become “a totally new player.” No one really means that, but everyone kind of knows what they’re trying to say — a big change, often unexpected, like a pitcher throwing harder than ever or a hitter launching more fly balls. Pérez has indeed become a totally new pitcher, but in this case it’s almost literally true. He reinvented himself by throwing a pitch that he’d never previously used in a game and is now dominating lineups with it as his primary weapon.

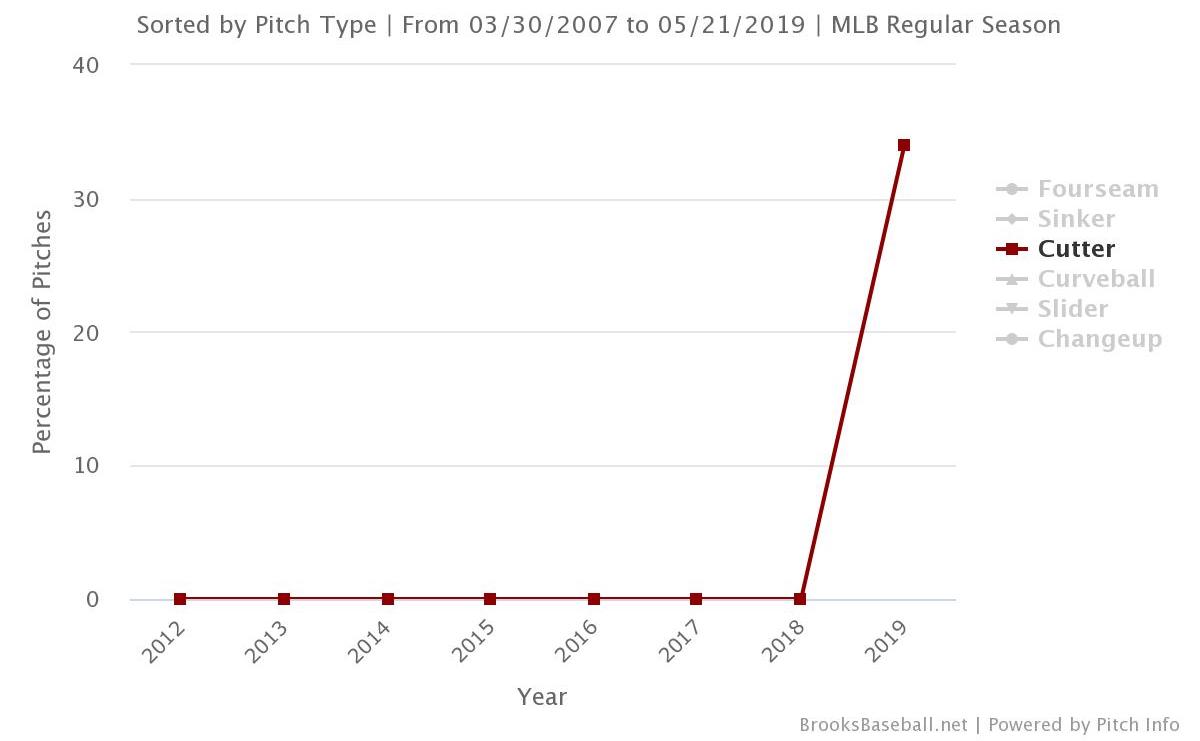

For the first seven years of his career, Pérez was a five-pitch pitcher: four-seamer, two-seamer, curveball, slider, changeup. It varied a bit by year, but he generally threw about 60 percent fastballs, 20 percent changeups, and 20 percent breaking balls. It was a fairly traditional mix, but with his career at a crossroads Pérez decided to make a very untraditional change. Motivated by his agent’s suggestion and then encouraged by the Twins’ coaching staff, he ditched his slider and began throwing a cut fastball.

It was a spring storyline in Twins camp — our own Matthew Trueblood even wrote about Pérez’s attempted changes as part of a larger story — but one viewed somewhat skeptically. After all, Pérez was hardly the first pitcher to start talking about tinkering with their repertoire following a rough season, and the Twins’ own grand plan with Pérez seemed even more focused on increasing his fastball velocity. They accomplished that, upping his average fastball from 93 to 95 mph, but the bigger change is impossible to miss.

Pérez has thrown a cut fastball 34.0 percent of the time this season — 297 cutters among his 874 total pitches — and opponents are hitting .104 with two extra-base hits and a .156 slugging percentage against it. He went from literally never throwing the pitch for seven years to throwing a version that Mariano Rivera would be proud to call his own, and suddenly it seems very important to note that the Twins’ one-year deal with Pérez also includes a $7.5 million team option for 2020.

With the help of Rob McQuown and the BP stats team, I went in search of pitchers like Pérez who added a prominent new pitch they’d never thrown before. What we found was some tricky data, as many of the examples were, in fact, prospects expanding their repertoire once they settled into a stable gig or pitchers of all ages moving from the bullpen to the rotation. I’ve done my best to parse the data and isolate the cases most relevant to Pérez truly “adding” a new pitch, but there’s more subjectivity involved than I’d like.

Here’s the other thing we found: There are zero examples in the past five years, subjective or not, of an “added” pitch being thrown as often as Pérez is throwing his shiny new cutter. He’s thrown 297 cutters, including at least 25 in each of his seven starts. Assuming he stays healthy and in the rotation, that puts Pérez on pace to throw roughly 1,000 cutters by season’s end. In our entire 2014-2019 database, even including examples not fitting the Pérez mold, no one has added a new pitch and thrown it more than 750 times.

The most-thrown new pitch from 2014-2018 was Jake Odorizzi‘s “splitter” in 2014, which is technically a split-changeup he learned from new teammate Alex Cobb after being traded from the Royals to the Rays as a 23-year-old top prospect. Odorizzi nicknamed his new toy “The Thing” and threw it 741 times that season, making it a huge part of his repertoire ever since. Five years later and now a splitter-throwing veteran, Odorizzi paid it forward by taking on the Cobb role and helping a new teammate learn a new pitch.

That new teammate? Martín Pérez. Full circles are a beautiful thing.

According to Dan Hayes of The Athletic — a must-read for Twins fans — it all started early in spring training when Pérez approached Odorizzi wanting to learn more about one of his pitches. Pérez asked not about The Thing, but rather about Odorizzi’s cutter, which he’s generally thrown 10 percent of the time. “It’s just a matter of hand positioning more so than anything else,” Odorizzi told Hayes. “I just moved his hand over on the ball a little bit and no joke, very first one he threw was … it was right out of the gate.”

Odorizzi makes the whole thing sound very simple and straightforward, almost like holding a door open for someone or giving directions when asked. Maybe it really was that easy, but even something like that can only take place if teammates are actively looking to learn from each other and, in the case of Odorizzi this spring and Cobb back in 2014, willing to share their knowledge to help someone else. Among the many good quotes Odorizzi gave Hayes, this one really stands out to me:

If we want to win, we’re going to need everybody at their best, so why not try to give somebody an extra weapon? I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a beneficiary back when I learned my split from Alex Cobb. Without that pitch, him teaching me when he didn’t have to, who knows where my career would be now? I kind of wanted to repay the favor. … I wanted to do the same for him. I know last year didn’t go how he wanted it to go. It could be a big pitch for him.

Not all players feel that way and not all teams have an environment where that type of behavior — both asking questions and sharing answers — is so encouraged. Three years ago the Twins overhauled their front office, hiring Derek Falvey and Thad Levine to drag the team into the modern era of data, technology, and analytics. This winter they overhauled the coaching staff, including replacing Paul Molitor with rookie manager Rocco Baldelli, in an effort to create exactly that sort of information-sharing environment.

Beyond that, the Twins targeted players to fit that approach. Three months before acquiring Odorizzi from the Rays last year, they hired Rays pitching guru Josh Kalk. Levine, now Twins general manager, was hired from Texas, where he was assistant GM for Pérez’s entire career. They added Pérez and Odorizzi because they thought each pitcher could help the team, but they also added them — and other well-regarded veterans, like Nelson Cruz on the hitting side — believing that they’d be open to helping others, too.

I talked recently to a member of the Twins front office about the concept of clubhouse leadership and they opened my eyes to a different way of viewing the entire concept, particularly as it relates to stories like those of Odorizzi and Pérez. Because so much of what actually happens in a clubhouse is seen only by players, coaches, and other team staff, fans are often fed a version of “clubhouse leadership” that stems largely from how players behave in public and/or around the media. But is that really what matters most?

Having a generally sunny disposition is never a bad thing and goes a long way in that regard, and a willingness to provide thoughtful quotes to beat reporters or television cameras can positively shape a player’s image even further. Those things have value, certainly, but some well-liked players offer zero tangible help to teammates behind the scenes and some media-phobic grumps go out of their way to share knowledge when no one is recording what they say.

Some players combine those traits, and the Twins have tried to collect as many of them in one clubhouse as possible. That’s not necessarily unique, but it’s a new twist on the old leadership cliches, at least. If someone has knowledge that can help win games, the Twins want it and they want it shared throughout every level of the organization. Anyone or anything stopping that flow — be it a manager, a coach, a player, or even a lack of technology and data resources — is now a candidate for swift change.

Maybe the Twins would have signed Pérez even if Levine didn’t know him so well from their time together in Texas. And maybe Pérez would have added a dominant new pitch without the help of Odorizzi this spring. What we know for sure is that the Twins acquired Odorizzi and Pérez because their key decision-makers were very familiar with them, both as pitchers and as people, and putting them on the same roster and in the same clubhouse has led to a combined 106 innings with a 2.63 ERA for a first-place team.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now