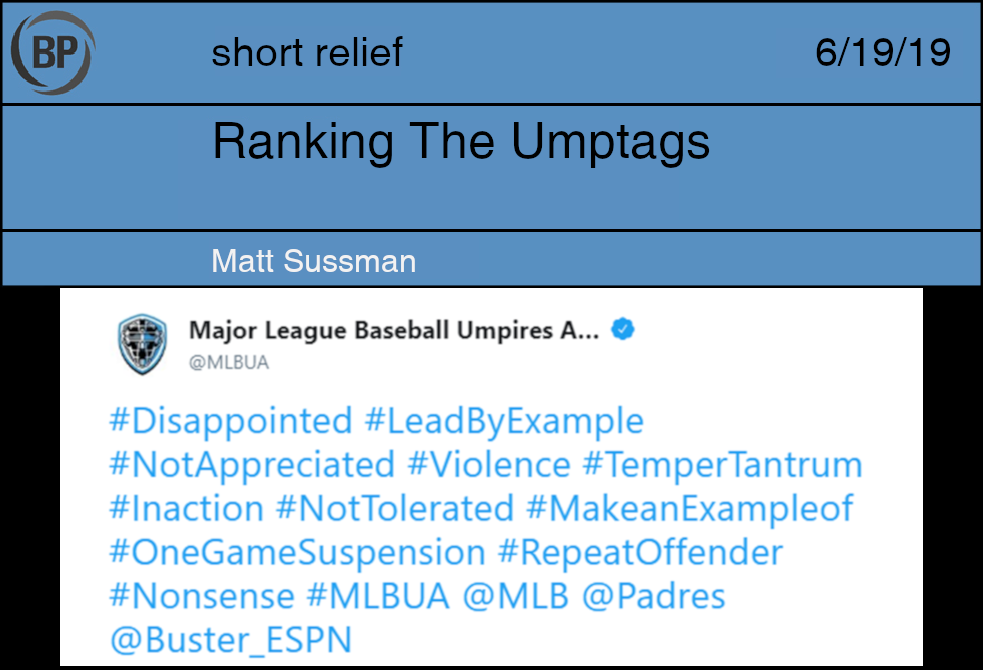

You cannot argue balls and strikes, and the rest comes down to instant replay. So when it comes to borderline calls, the only ones we can (and should) question is their decision to post. So let’s rank the hashtags used in its promotion:

- #OneGameSuspension – This one’s completely accurate. It is about a one game suspension. Full points!

- #MLBUA – Good use of creating brand awareness for your union!

- #Disappointed – A sensible opening sentiment, I suppose. You are disappointed in all this. Good to use emotions in the first person.

- #NotAppreciated – Okay, so are you the ones not being appreciated, or do you not appreciate the—

- #NotTolerated – Again, who’s not being tolerated here

- #RepeatOffender – Pete Offender and Repeat Offender went fishing. Pete Offender fell into the water. Who was left?

- #LeadByExample – Fair enough, the rest of us are also making bad posts on social media, you’ve made your point.

- #Violence – The backstop is not unionized, though I appreciate your concern

- #Inaction – I don’t know, seems like they took action and you just didn’t like—

- #TemperTantrum – Yeah I suppose what’s what I’d call this

- #Nonsense – Even more succinct

- #MakeanExampleof – I have a vivid recollection of my high school biology teacher, an eccentric fellow, teaching subject material to us, with some other kids in the hall talking, and out of nowhere he broke his concentration and ran into the hallway yelling ‘DON’T END A SENTENCE WITH A PREPOSITION’. Hashtags did not yet exist but I imagine the sentiment would persist.

During the offseason, I had a dream about Marwin González. In it, I was an adopted member of his family. I was extremely close to his mother and aunt, who treated me like a third sister. We walked arm-in-arm while Marwin and his wife tended to the children with great sensitivity and tenderness. We were a family of very tiny people, only a few inches tall, and we were on a long and dangerous trek across the floor of the dining room of giants. Marwin’s father led the way, holding before him a radiant pendant at the end of a short chain. When we saw an answering light from the other side, we crossed under a table to safety.

This season, I needed a team to attach myself to, and because of my dream, I picked the Twins. It was a great choice. My dream left me feeling euphoric, and the Twins have done the same in their own way. Not only that, but González has been hitting pretty well. I feel good about him, as if I have residual, and completely imaginary, family pride.

In 2007, I dreamed that I fell down an elevator shaft. I would have died except that Manny Ramirez dove in and saved me. That year I rooted for the Red Sox, and it was such a happy season, especially when Boston cruised through the World Series in an easy and predictable win. Yesterday, as I watched Minnesota and Boston play each other, I indulged a silly question. Can I dream a team to a World Series victory? What if, in 2011, I dreamed that Adrián Beltré pulled me from a burning vehicle? What if, in 2014, I dreamed that Billy Butler and I restored a decrepit villa in Naples, or what if, in 2016, I dreamed that Terry Francona was my partner in a dance contest on a beach in Bahia? Would things have turned out differently those years? Would the Rangers, Royals, and even Cleveland have raised the trophy instead of going home without it? Did all those teams lose for the lack of a dream, specifically, mine?

I don’t know. How do I, a sensible and modern woman, rule it out? I don’t even know why I dream to begin with. The brain does its own thing and doesn’t let me in on its decisions. It produces elaborate dreams, haunting me with intense feelings of joy, fear, and sadness, but it doesn’t ask my permission first. So what if? What if, just like the Red Sox in 2007, the Twins are going to go all the way? Will it be because I dreamed of Marwin González and our pack of tiny, intrepid travelers? I wouldn’t put any money on it, but still, why not?

A lifetime ago, I was a mediocre substitute teacher. Not that it’s an easy job: You hunt down someone else’s office, decipher the hasty, often fever-soaked scribbles laid on the desk, and prepare to hand out the mind-numbing busywork of packets and textbook assignments that are the only tasks they can entrust you with. The students appear, and they are equally skeptical: They see you as a free hour, a break from the monotony of their steady improvement and maturation, a country yokel in their cosmopolitan classroom. Your day is six hours of one-on-thirty combat, each student testing you.

I was a mediocre substitute because I, foolishly, chose to build my teaching identity on charisma. Each prospective teacher faces the problem of classroom management and decides how they’ll choose to handle the unruly class. Some don the armor and the permanent sneer; they tend to do well, whether or not the students do. Others lecture their assailants into unconsciousness. Some naturally defuse conflict the way the rest of us breathe. The charisma path is as good as any for the classroom – we’re stuck here together, it’ll probably be easier if we try to get along – but it’s useless for substitutes, who never have the time to build rapport. That’s why substitute teachers so often feel compelled to put their authority on display, even before the situation demands it.

The umpire’s union drew criticism for their public reaction to Manny Machado’s one-game suspension, and that criticism is entirely merited. But when I read it, especially the more detailed Facebook post, I just felt sorry for them, especially for that tiny phrase: “of authority.” It’s so small, and in another way, so much smaller. I largely sympathize with umpires; it, too, is a difficult job, and one at which I am uniquely terrible. But the saddest, most desperate type of authority is the kind one needs to keep announcing, like the person who reminds their colleagues that they are very, very smart.

The commonality between bad umpires and bad substitutes, beyond the irrational ejections, is that they both demand respect, as though respect could ever be earned by asking for it. It doesn’t work that way. Authority is just something you have; that’s the tragedy of it.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now