I – You’re left wondering how long he thought about doing it. He takes off without hesitation the moment Alcantara drops his head. Was it observing some pattern pre-game? Some trend an eagle-eyed staffer identified through hours of watching isolated footage? A simple wager between teammates? Did he think about it all year? Did he think about it last August, when infection robbed him of his motor function, and threatened his life?

II – It’s not a profundity to observe that sitting around in a hospital bed, unable to get up, unsure if you’re going to live or die has a way of framing your agency in your own life. When living is reduced to four walls, basic cable, and the tubes in your arm, the things you used to do, to be, slough off the psyche pretty quickly. After long enough, all that’s really left is the essence of who you are, of the things you truly care about. They become the only thing you can think about and, I truly believe, can help you survive.

When he was released from the hospital after two-weeks of life-and-career-saving treatment Martin said, “The most important thing is I get to see my family, my kids, and play baseball again.”

III – The natural order is out to get us, and the natural order, eventually, will win. We make jokes or roll our eyes at those with more than us. We say someone was “born on third base and thinks they hit a triple.” But regardless of where we start in life, the game state will eventually demand we run from it, and then we are doomed. The sense of safety is an illusion born of necessity, and we are always stealing it from an indifferent reality that will eventually kill us.

We might as well point ourselves at home, wait for an opportunity, and run like hell. A moment of safety, stolen from the void.

In Blaise Pascal’s Pensées, published after his death in 1662, Pascal sets out what is known as “Pascal’s Wager”: in short, that any rational person ought to live as if God (and the attendant heaven/hell) exists. Wager that God is real and lose, and all that’s really lost in the wager is a lifetime of doing good works and not taking the Lord’s name and so on; a moderate investment, Pascal concludes, considering the extreme range of outcomes if God does, in fact, exist, and one’s path is either strumming a harp from atop a puffy white cloud or dancing the fire-dance in iron shoes for all of eternity. It’s a logical enough proposition, although one that seems pragmatic to the point of cynicism. Point your feet in the direction of belief, Pascal seems to be arguing, and the heart will get dragged along for the ride.

On Monday, Padres prospect Logan Allen made his major league debut. This in itself is not particularly noteworthy, although MLB debuts are always somewhat noteworthy, especially when the player in question was drafted in the 8th round with a less-than-20% chance of making it to the Show. What made Allen’s debut stand out from the 130 other players who have made their first MLB appearances this year is who showed up to watch it, and why:

Tonight, @Logan__Allen earns his dollar from @JohnCena as he makes his Major League debut.

Tomorrow, the dollar gets paid in person. #onedollarbet pic.twitter.com/HKecAkSuS4

— San Diego Padres (@Padres) June 18, 2019

John Cena, it turns out, was out to eat a while back with a Padres fan friend who recognized Allen, and the two wound up involved in a lengthy conversation that ended with Cena betting Allen a dollar he wouldn’t make it to the bigs, because…motivation? Per Cena, he could tell Allen had “very rarely faced failure,” and he was wondering how he could create a situation for this person who–and this cannot be stressed enough–he had literally just met in order “to face him with the concept of failure.” One can only assume this meeting took place before Logan Allen gave up 15 runs in 14 innings in Triple-A El Paso. So: the bet was placed, hands were shaken, Allen eventually works his way up to his MLB debut, Cena shows up with the dollar and spins it as a feel-good story.

Except it’s not.

This is Pascal’s Wager dressed up in baseball pants. Cena can frame it as “motivational,” but he’s making a low-risk investment with potentially huge payoff. Like Pascal’s rational man who donates to charity solely because it’s on the checklist of Good Person things, he is committing dollars but not his soul. Meanwhile, when Logan Allen did defy the odds and make it to the majors, Cena could come collect on his wager, smiling down from his suite, saying “I knew you were the real deal all along.”

Turner Classic Movies celebrated the 30th anniversary of Field of Dreams this past weekend with a brief theatrical re-release, even though it debuted in theaters during the month of April. I shrugged and figured this was another case of TCM on their own temporal trip, taking their sweet time with things. Then social media and baseball telecasts bombarded us with Father’s Day tributes, and my tiny brain put two and two together.

I have a strange relationship with the movie. Most people have binary feelings on it: it sucks or it’s good. I seem to like half-heartedly defending parts of it, even though I only saw the film from beginning to end once.

There is no good excuse for the lack of Negro League players.

Shoeless Joe Jackson was a lefty hitter, not a righty like Ray Liotta portrayed him. Liotta tried for a month to learn how to hit lefty, the director was apparently horrified at how he looked and decided the penalty for historical inaccuracy was best incurred over viewers watching Liotta’s pathetic excuse for hitting. I really want to see Liotta’s attempts. Was his instructor a future launch angle enthusiast? I care more about the details of this failed attempt than the inaccuracy, so maybe the director was right.

Kevin Costner asked his ghost dad if he wanted to “have a catch.” Some people say “play catch.” It’s a whole thing. Did you know that in the book the movie is based on Ray Kinsella asked his old man “Would it kill you again if we partook in a friendly of catchball?”

The ending is corny. That’s kind of the point. I’m glad you have a great relationship with your father. When I think of my dad and I playing catchball, it’s of the time he was trying to help me get over my fear of getting hit by every single Little League pitch by throwing me some BP in my elementary school’s concrete yard one summer afternoon. I insisted he was throwing inside, and it was all the more irritating because he was left-handed, so he must be purposely doing this to get in my right-handed pots and pans. I insisted we briefly switch roles to show him what I meant. I didn’t mean to bean him with my first pitch; I honest to God wanted to maybe shuffle his feet a bit. He had enough and drove home. I walked the ten blocks back to our apartment. Leisurely.

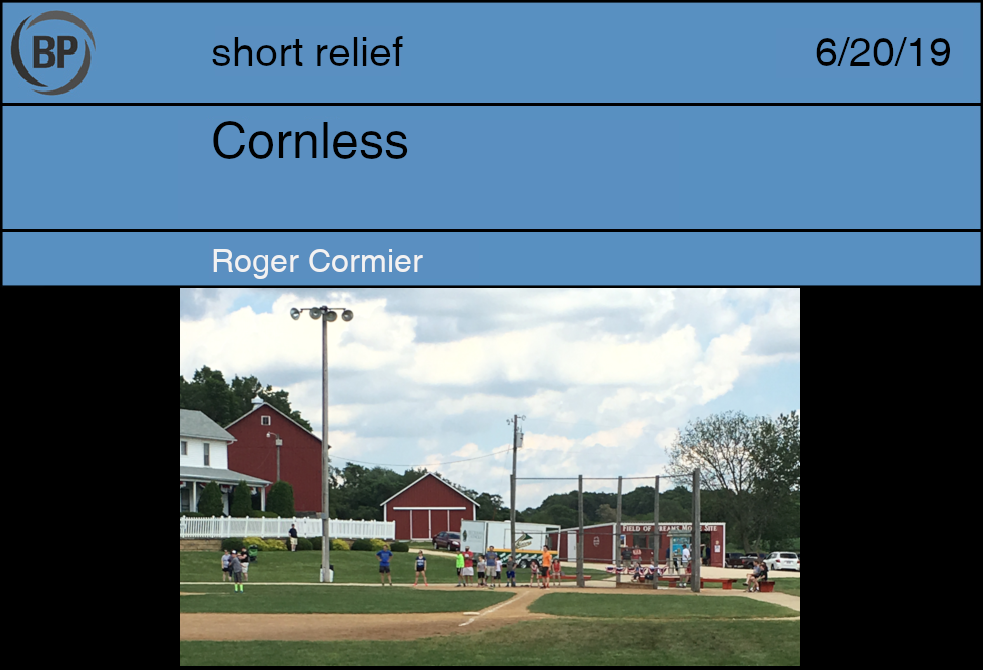

Funny thing is, until TCM reminded me, I kind of forgot that I’d visited the field in Iowa three years ago during Memorial Day weekend. I didn’t mean to go. I was visiting someone in Iowa, the field is in Iowa, and surely it’s Iowa, it can’t possibly be that far away from Iowa City. It was something like a two hour drive to Dysersville, a town whose name I’d also long forgot while never forgetting the neighborhoring location with amusement (Farley. Farley, Iowa.) It was definitely long enough for an argument with the driver over the apparent directionlessness of my life, and my feelings towards hearing this obvious truth. But we got there. Here is a picture:

Yep, that is an adorably simple power line just waiting to get hassled by a lazy pop-up between second and third base. You might also notice the lack of corn.

The breeze smelled like poop. One kid kept pulling his father’s soft-tosses foul. It was amazing he kept making contact, but I was too busy annoyed at the kid for his failure to adjust to appreciate it.

The wind eventually shifted direction. I roamed the warning track. We sat on the bench for an hour. On the drive back we agreed the one-word synopsis of our experience was “peaceful.”

My father died the next April. I had not interacted with my Iowa companion for something like eight months by that point. She knew I had not spoken to my father in something like ten years. She probably knew the baseball story. She emailed me anyway. She said something about how sometimes in life things are truly binary and either suck or don’t suck, and my father dying sucked. I told her I agreed.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now