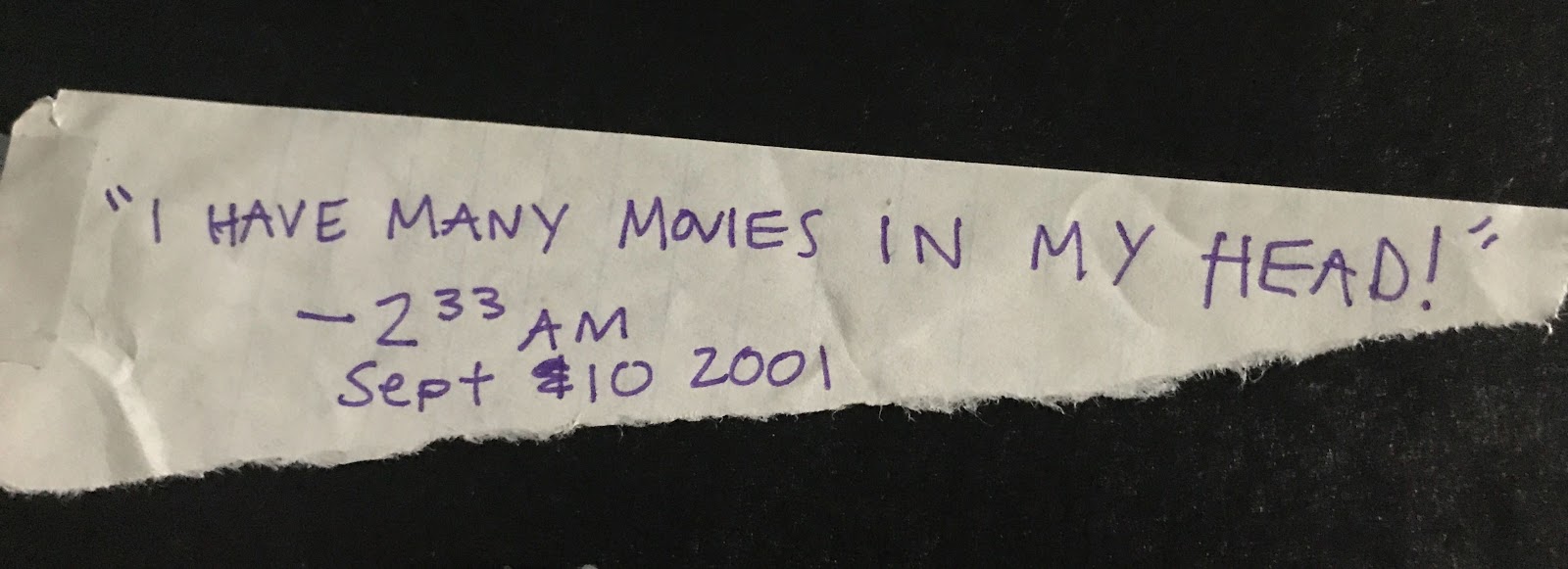

At 2:30 AM on September 10, 2001, Nicole sat on the floor of my dorm room and mapped out her future. She wanted to put her own spin on kaiju, the giant monsters popular in 60s Japanese films. She had studied abroad in Japan last semester, walking where Kurosawa had walked, as inspiration for her own all-female version of Seven Samurai. “I have many movies in my head,” Nicole told me, smiling, and as someone struggling with my own art, it was the most inspiring, beautiful sentence I’d ever heard. I scribbled it down, with the date, on a scrap of paper and gave it to her.

Two mornings later, I woke up in my dorm room, walked across the quad to my on-campus job in the writing center, flicked on the TV and watched the world as I knew it explode. A week later, the campus chaplain came to my floor and called us out into the hall to tell us Nicole had died. She’d been having a routine medical procedure and somehow it triggered a bacteria that attacked her organs, shutting them down. I don’t exactly remember the details. All I remember clearly is crumpling instantly to the industrial-grade carpet, like the shock of the news kicked me right behind the knees.

The passage between life and death is always difficult, but a young person dying is an affront to the natural order of things, and a young person dying unexpectedly can turn the world upside down and shake it. It is the cruelest reminder that our employment on this earth is at the will of something entirely outside of ourselves. And even though it’s not productive in any sense, it’s impossible to look at that thread of life cut short and not wonder what would become of the rest of it, with so much thread left to unspool, so many movies still in one’s head. The beautiful and maddening thing about being human is that dreams engender dreams. I have never met anyone who, having accomplished a goal, did not almost immediately turn their sights to something else. That’s how it is, with dreamers. There’s always another country to visit, race to run, mountain to climb, movie to make.

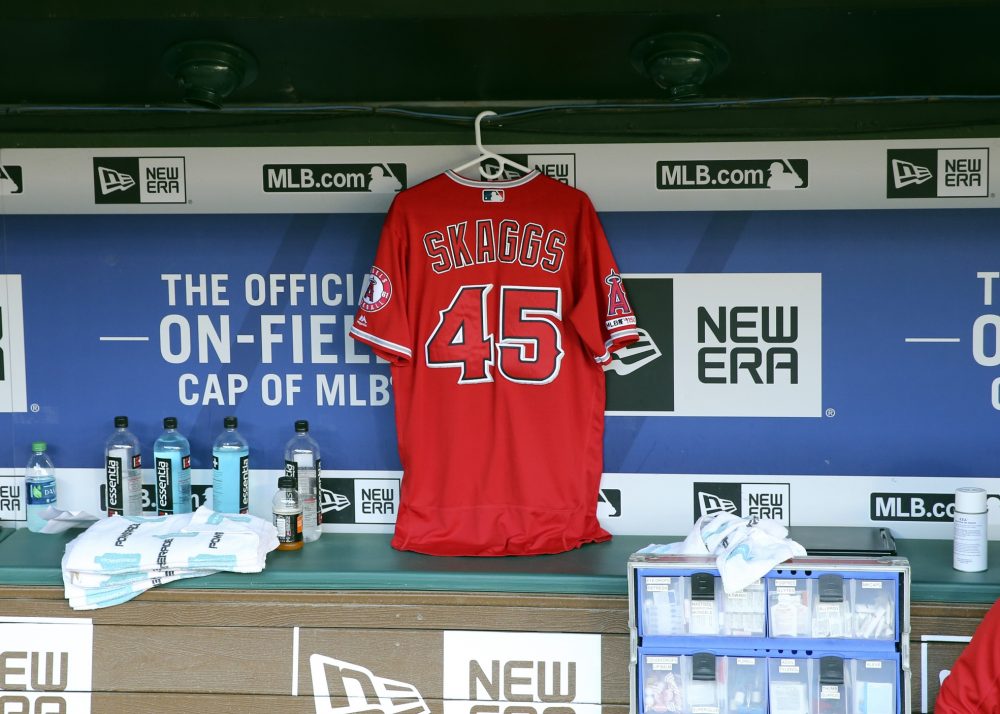

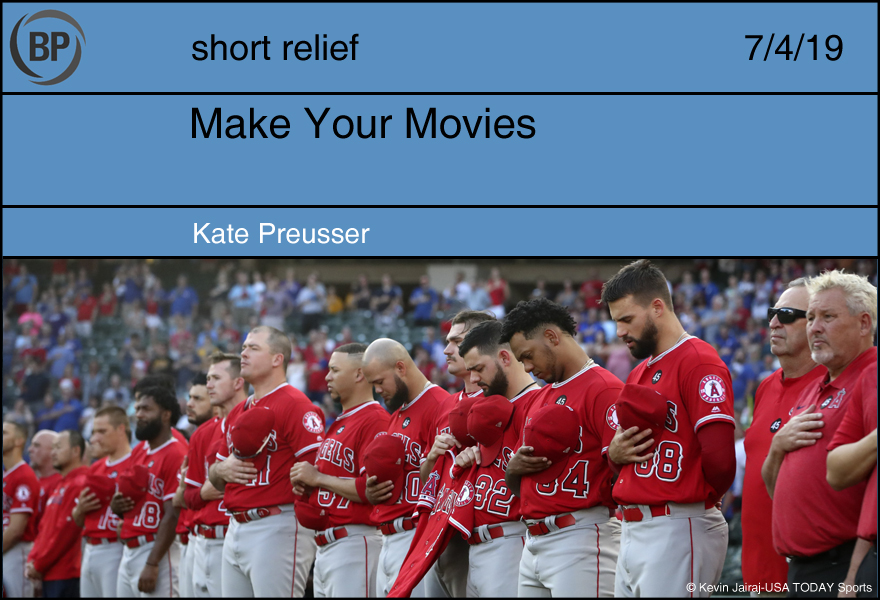

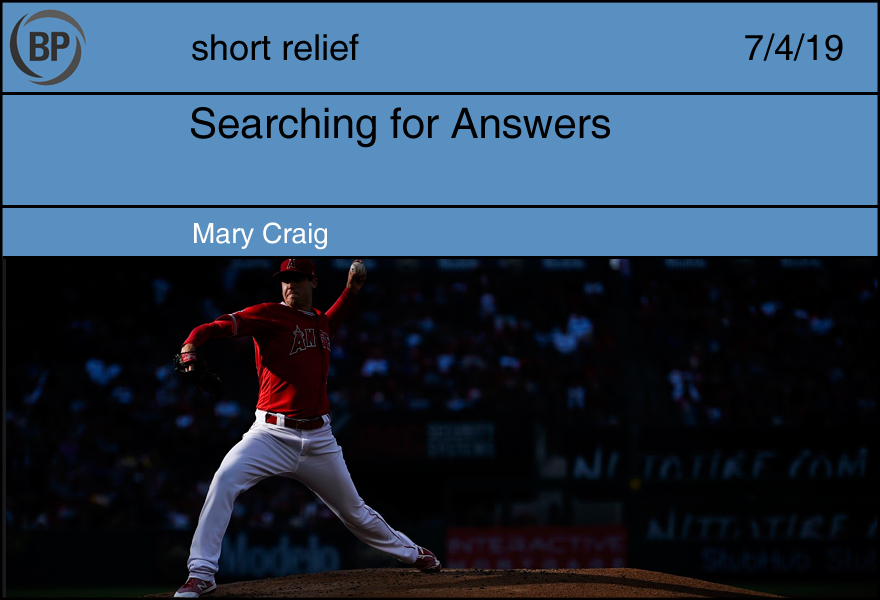

Less than twenty thousand people have earned the right to call themselves Major League Baseball players, and Tyler Skaggs was one of them. Of the roughly half of that number who are pitchers, an even smaller number will reach Skaggs’ mark of 500+ innings pitched, earn a job as a regular member of the starting rotation, or battle back from multiple injuries as Skaggs had. Skaggs also was a first-round draft choice, an elite fraternity within the already small college of MLB, and something nearly every high school player in the country sets their sights on.

But for all these dreams achieved, Skaggs had more in mind. The Santa Monica native wanted to wear the Angels uniform when he played at Dodger Stadium later this month, a true California kid. He had just gotten married in the off-season to his “forever travel partner,” with more adventures planned. “2019 let’s get it!” he captioned a video of him pitching before Opening Day, because when Mike Trout is your teammate, dreaming on a championship never feels all that far-fetched.

When Nicole’s parents came to clean out her dorm room, they asked us to select a memento from among her things. I chose a bowl she’d brought back from Japan that I had admired multiple times. The bowl sat on her desk, under her bulletin board, where she’d pinned up the scrap of paper I’d scrawled on back before the world fell apart.

Life is in short supply; dreams are not. Make the movies that are in your head.

The first player death that got to me was a University of Toledo basketball player named Haris Charalambous. It was a name you couldn’t forget. He was a large awkward teenager (6-foot-10) that played five minutes a game, *maybe* scored a point and a rebound if he was lucky. He collapsed while jogging during a team conditioning in 2006 and died at the age of 21. A banner hangs from the rafters in his honor, tucked all the way in the corner, next to scads of division titles and NIT appearances throughout the team’s history.

I think of Charalambous (because with a name like that, how do you not) every time I see a player death. I was familiar with Skaggs, having penned his BP annual comment twice, including this past year, but I didn’t watch him as intently as so many Angels fans. They spent so many hours working to play for themselves but entertain us in the process. Instead they’re remembered for passing away all too soon. It is not the legacy they chose, but the one that was chosen for them.

So if there’s any takeaway, it’s to remind ourselves not to get wrapped up too much in equating one’s worth with one’s numbers. Skaggs had a career 4.8 WARP. Charalambous scored 29 points in 29 minutes. What do those things even mean? There’s never been a great answer on how to process the grief, but I’ve found this helps: seek out their stories, listen to them, and share them. Charalambous, one of the first Manchester, England natives to play Division I basketball (John Amaechi was the first and most famous), has an annual basketball tournament in his hometown. His mom and sister still attend every year. Skaggs will no doubt have something in the future to perpetuate his memory, and that’s going to help all of us.

Baseball has always been an attempt to explain the inexplicable, to quantify the things our eyes can’t comprehend. Every generation, we inch closer to a more complete understanding of the game, a better notion of how it’s possible to throw 100 mph or successfully hit a round ball with a round bat. But beyond the mathematical and scientific elements, every so often something happens that will never make sense, that makes us doubt our quest to obtain a wholly rational understanding of baseball.

We love finding reasons for the way things happen, understanding causes and assigning blame. There is obviously a scientific reason why Tyler Skaggs died, but that reason, whatever it is, will never fully make sense to us. Sure, we’ll probably arrive at a cause of death, but we’ll forever be in search of why he died. He was only 27 years old, an elite athlete seemingly in perfect health, a beloved member of his community who tried to give back as much as he gained. His death will never make sense because it isn’t fair.

By all standards of justice and how we measure a human life, he shouldn’t have died. He should have lived until the decades greyed his hair and slowed his step. But he didn’t, because that’s not how things work. People who deserve to die live long and prosperous lives while those who deserve to live are taken from us so quickly, all we can do is stare in disbelief at the place they once were.

In the ensuing weeks, months, years, as we grapple with what his absence means for our continued presence, we’ll see him everywhere. He’ll be lurking in the dugout and the bullpen and the mound. He’ll be smiling along with his teammates as they learn how to smile in the face of grief. He’ll be holding our hands as we walk back through his 27 years of life, hoping to find in it permission to live, to laugh, and to forget. Because life does go on.

We’ll do our best to remember him, as much for his memory as for ourselves. But for many of us, he will slowly fade away. It will start with feeling guilty about yelling at a player, but that guilt will disappear, and we’ll return to watching and talking about baseball as normal, whatever that is.

The next senseless tragedy will bring it all rushing back, and we’ll wonder how we could have slipped back into a life not defined by tragedy. We’ll berate ourselves for failing to appreciate players as human beings, for calling for relievers or bench players to be DFA’d, for tweeting in frustration over poor performances, for valuing wins above people’s humanity, for tricking ourselves into thinking rational calculation is the best way to understand the sport.

We’ll return to our quest to find meaning in death or to again abandon it when it becomes fruitless and we are called back to the urgency of our lives. Eventually we’ll realize that the meaning we’re searching for doesn’t reside in death, but in life and the fact that against all odds, it continues.

A former student of mine died a few years back, before his 20th birthday. If I’m honest, I don’t remember how he was as a student – polite, definitely; attentive, possibly; how much he liked or didn’t like high school biology, I don’t know. I could tell you which class section he was in, where he sat at one of the long cafeteria benches that were my room’s ‘lab tables’ my first years teaching, who his friends were. Mostly, I remember him leading his younger siblings to a nearby elementary school each day, how they trailed like ducklings behind him, how much was put onto my student’s narrow teenaged shoulders, how much those kindnesses are and what should be remembered.

There’s no education coursework for that kind of loss, nothing that could have prepared me for the shock of absence – not just loss of life but loss of potential. How young people think of themselves as immortal until you start to think of them that way, an infinity shortened into a fixed distance.

I didn’t know Tyler Skaggs or Yordano Ventura or José Fernández or any MLB player in a meaningful way. I don’t know them, or their families, or what the million small kindnesses that make life bearable were for them, or what kindness they gave others. I only know that they were roughly the same age when they died as my student would be now if he’d lived.

And that baseball is a game that could go endlessly but averages out to about three hours. A game where the ball travels with magnitude and direction, a vector, until it’s abbreviated into a catch. A game where possibilities beget possibilities beget possibilities. A game meant to be played in summer, and in the summer of one’s life. And that, like people, it holds both greater and lesser infinities for those who care to look for them.

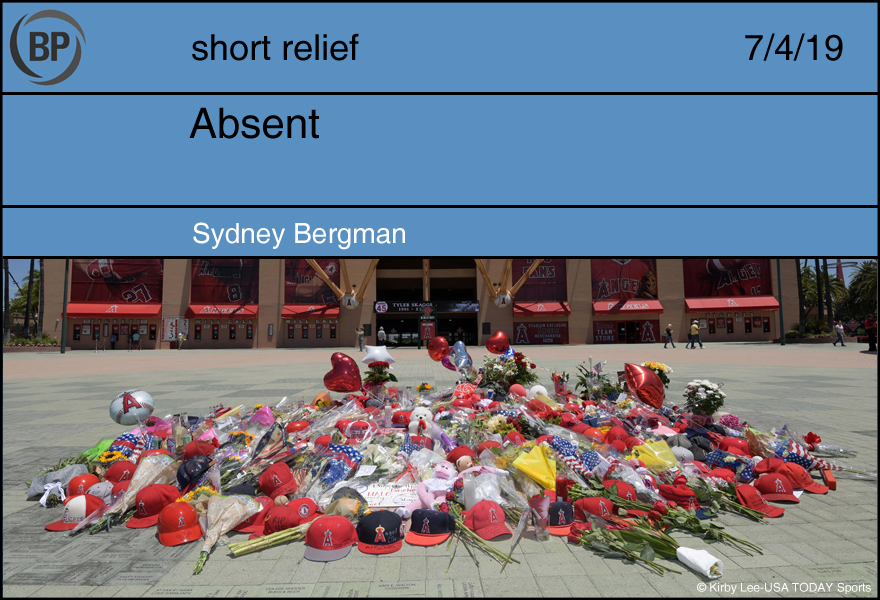

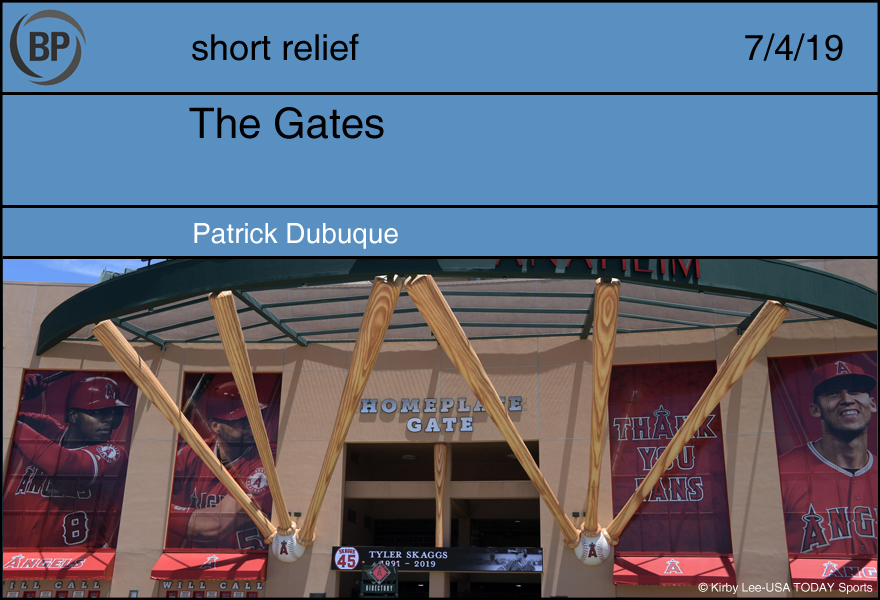

Most people hate the metal detectors they put up outside baseball stadiums, and I understand that. Me, I like that pause, the inglorious city sidewalks and dull gray cement just outside the stadium, the crowd noise seeping out like a whisper, a stark contrast. I like the resistance to entering the gates, the change in light and temperature and volume and pressure as you emerge through the plastic, permeable gates, cutting through the surface tension like a sheet of water. Keep it all in here, build up the walls, trap the souls, seal them in so that the baseball can’t escape, so that it can never age.

“I’m getting so big,” my daughter notes cheerfully as she sits among her Legos, stretching her impossibly long legs. How did it happen? How did I carry that body, those spindly legs, in darkened, night-drunk circles of infant screams? How much longer could they get, when will I be unable to carry her? I need to take her to a ballgame. I need to accompany her through those same gates, enshrine her happy little face along with Dave Henderson and Dave Niehaus, Darryl Kile and Roy Halladay. I want her to create her own stadium, her own statues, and one for me, even as the lines appear on my brow.

Baseball is the opposite of death, after all; it never stops breathing, not even in wartime, not even in tragedy. It is made for banners, an intricate scrapbook. It lives but does not move, a shimmering watercolor rendition of each person’s favorite moment of youth, even for the ones who did not have one. The perfect baseball has no endings, only fractions of fractions. No pitch should ever reach the plate, no home run should ever land, and no baseball player should ever die. None of us should. We should all live forever, together, inside those walls.

Psalm 13

“How long shall I harbor sorrow in my soul, grief in my heart day after day?”

What if I told you that grief lasts forever? Would that be so bad? The wind pounded the house the day that my Davey died; that night, numb, I took out the trash. The dark wind yanked the gate off its hinges and struck me in the head. Yet the shock passed, as did the pain. The day eventually arrived when I stepped out and nature had stopped howling. I wasn’t surprised by the sudden peace. I heard a bird sing and noticed the lazy deep blue of the sky. Does that mean I no longer grieve? That doesn’t seem possible. I loved him forever. Forever was still ahead of us, and I loved him forever just the same. I pledged my heart and our love was sealed. Would I now let go of my love? I could never love him less, so still I grieve.

Psalm 42

“Deep calls to deep in the roar of your torrents, and all your waves and breakers sweep over me.”

Let us recall that moment when we heard the news: where we were, what the weather was like. The kind of moment we needed but didn’t get, consumed by schedules, by game time, air time, tweets to be sent, all consumed, uncomprehending. We went on the air at the scheduled time but we were honest, this hurts, I don’t have words, I have to tell you, I just can’t say anything that will help you. Life is not superficial; getting the groceries, mowing the grass, making jokes, playing catch, the day-to-day of weight and meaning. A gift. Every pitch matters; we don’t need loss to remind us. We need grace while the sea resets its shores.

Psalm 88

“Do you work wonders for the dead?”

The clouds stacked above Globe Life Park clambered over each other, colossal piles of condensation jockeying for a better view. Their glorious faces turned upwards, expectant, taking in the new guy who, as we all hoped, was looking down on us. Our thoughts rocket upwards in that first instant of loss. The shock will seep away, the heaviness will seep in, and for how long? We fear it. Our hearts can crush us, so instinctively, we look up. We put our hope in heaven, to give him a new home. We put our hope in God. Please don’t let life end. Wonder of wonders, we know it’s happened. Without thinking, we know it’s true. Tyler is safe and happy and it’s okay. We can be sad.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now