*Please note that the following review contains spoilers, such that they exist regarding movies entirely about the past.

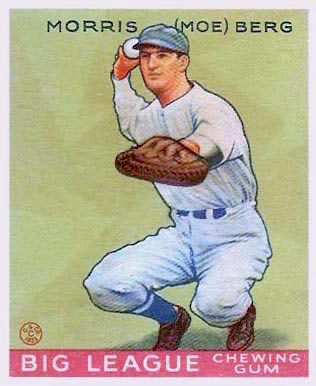

The tensest moment of ‘The Spy Behind Home Plate,” a documentary about Moe Berg now playing, comes at a moment of inaction. Berg, having been deployed as a field agent for the then-nascent Office of Strategic Services (precursor to the CIA), and tasked with assessing the Nazi German government’s progress on building atomic weaponry, decides not to shoot German physicist Werner Heisenberg.

Berg was born in 1902 in New York City, the child of Jewish immigrants, whose father had left Russia due to both pogroms and to escape what he felt to be the compulsory religious observance of the shtetl. His family moved to Newark, New Jersey, when Berg was 8 for the ‘good air’ away from the city. (Such movement wasn’t unusual; my grandfather, born around 1906 in Manhattan to Litvak immigrants, moved to Brooklyn for similar reasons.)

The film, made by D.C.-based Jewish filmmaker Aviva Kempner, traces Berg’s playing career from Newark – where he emerged as a talented student and baseball player, adopting the world’s most goyish pseudonym of “Runt Wolfe” to play for a local church’s team, as Jews would not have been permitted to play – to his admission to Princeton, which was then operating on quota systems for admitting Jewish students. Berg was enough of a sportsman to gain an invitation to join a dining club, then a bastion of ultimate-WASPery, but declined when it became evident that he was not to invite other Jewish students to join as well.

The film, which interviews Berg’s relatives, teammates, sportswriters, and historians, doesn’t touch on Berg’s relationship with religion or political leanings, instead mentioning that Berg thought of himself as a ‘patriot’ first and Jewish second. It becomes clear that America at the time wouldn’t let Berg operate that way, a careful parallel to later in the film where Berg infiltrates Nazi-occupied Italy in order to ascertain how close German scientists were to building functional nuclear weaponry. Berg, if discovered, would have been treated as Jewish, irrespective of his observance or lack thereof.

During playing time with the Brooklyn Robins (now the Dodgers), Indians, Washington Senators, and Red Sox, Berg proved himself a fine defensive catcher, which then, as now, meant he was more valuable behind the plate than at it. In the words of a teammate, Berg could speak a dozen languages – but not hit in any of them.

Berg’s ability with languages – he spoke at least 10, anomalous even at a time when many Jews of Eastern European descent were multilingual – is likely what made him attractive to intelligence organizations. Selected for two baseball goodwill tours of Japan, one in 1932 and then the legendary MLB All Americans team in 1934 that included Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, Berg learned enough Japanese to later do a broadcast address to the people of Japan following Pearl Harbor.

The film raises questions as to when Berg’s playing career turned to intelligence work. Well before he joins the OSS, he carries with him a letter from the state department on a trip to Japan, and photographs and films Japanese infrastructure and the Tokyo skyline, the latter of which he does by disguising himself and sneaking onto a hospital roof.

Conspicuously missing from the film is anything about his religious beliefs – or personal politics beyond being anti-fascist and anti-Nazi. He’d played for MLB teams during league segregation; an avid newspaper reader in addition to being a professional player, he was unlikely to miss the broad push for integration – in baseball and beyond – being made in the press.

While the film traces the details of his spying during World War II – including recruitment under OSS director ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, reports that eventually reached FDR, an encounter with Einstein – it glosses over his life after the War, including his advocating unsuccessfully for the CIA to send him to Israel or a failed mission in spying on Soviet atomic capabilities. His relationship with his brother Sam, a doctor sent to Nagasaki to treat survivors of the nuclear bombing by the US, receives a similar treatment. The film reports that Berg and his brother never spoke of Sam’s involvement in the bombing aftermath, but that silence is, itself, telling.

Noticeably absent is Berg’s own voice – for a man who spoke at least 10 languages, he’s a mostly silent figure in his own film, aside from a few reports and missives about the delights of 1920s Paris. And of course, “Pitchers and Catchers,” his seminal 1941 essay in the Atlantic on baseball.

Back to that non-fatal encounter with Heisenberg. The OSS sent Berg – with a pistol, cyanide capsule, and ill-fitting shoes meant to imitate European styles – to Zurich, to a lecture given by Heisenberg on what the agency hoped would be German capabilities for building nuclear weapons but what turned out to be on S-matrix theory. Berg received an invitation to dinner with Heisenberg (this was not a coincidence as the lecture organizer was a Swiss physicist and fellow OSS operative) following the lecture, eventually walking with Heisenberg back to his hotel. He chose not to shoot.

Such a calculation seems impossible – Berg’s German was good and understanding of physics solid for someone who’d spent his professional career as a baseball player. How much was he willing to risk assassinating Heisenberg – which would mean likely capture and death by suicide or by the Swiss authorities – with the knowledge of what would happened if he misjudged the Nazis’ capabilities? It seemed ludicrous to ask something like that of someone who’d spent his career calling pitches. But perhaps there’s some logic to it as well.

Or better stated in Berg’s own words, from that famous essay: “And this brings us to a fascinating part of the pitcher-hitter drama: Does a hitter guess? Does a pitcher try to outguess him? When the pitching process is no longer mechanical, how much of it is psychological? … The guess is more than psychic, for there is some basis for it, some precedent for the next move; what is past is prologue. ”

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now