Of the wide band of human emotions, grief is the most elusive, the most chimerical, as distinctive to each person as a fingerprint, as impossible to pin down as rain. In college I had a friend who died suddenly and for months afterward her mother, whom I did not know before the tragedy, emailed me daily, asking about my life, classes, the campus happenings. At first we spoke of her daughter, my friend, like she was on a study abroad trip somewhere distant and wondrous; after a while we did not speak of her at all, and then one day, shortly before graduation, she stopped responding to my emails. It never hurt my feelings; I instinctively recognized that she needed me to be a portal through which to view her daughter’s life as it might have been, to put me in her place for those few agonizing months, to read my letters back from school and imagine they were coming from her daughter. Sometimes individual griefs can line up like this, a sympathetic magic; other griefs are wilder, untamed, slashing through the forests of a person’s life and burning anything in reach. The process is individual, non-linear, and entirely unpredictable.

One thing that is often common in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy is a desperate attempt at meaning-making, a frantic accounting to make the karmic books balance. These meaning-making attempts help fend off for as long as possible what Joan Didion, in The Year of Magical Thinking, calls “the unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaninglessness itself.”

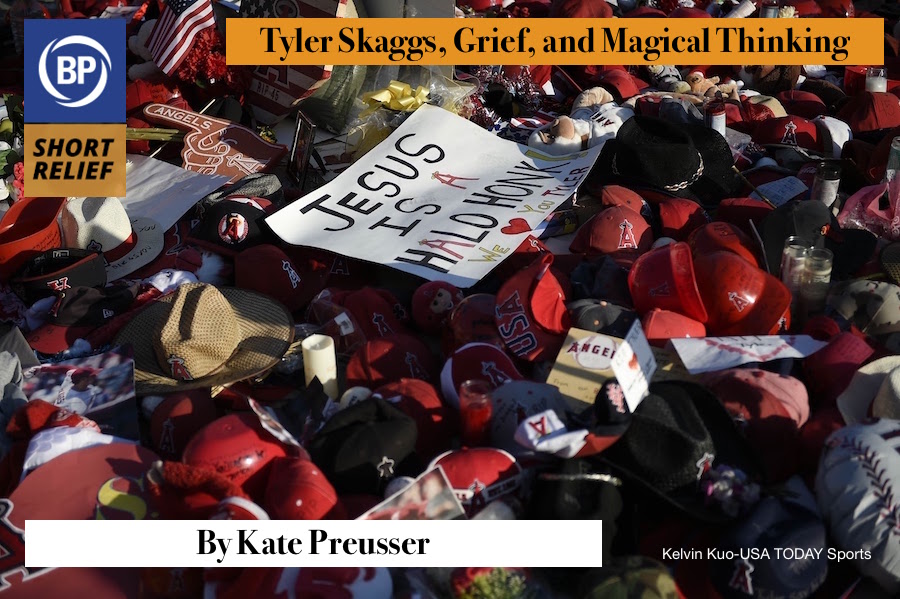

For many people – the religious, spiritual, or other – searching for signs can be part of that process. On the Angels’ first home game back after the tragic, unexpected loss of pitcher Tyler Skaggs, the team pitched a combined no-hitter against the lowly Seattle Mariners. Soon after, tweets like this started to pop up:

The story will give you chills.

• Tyler Skaggs’ mother throws first pitch

(Angels throw no-hitter)• Trout hits HR exactly 454 ft

(Skaggs wore No. 45)• Franchise’s 11th no-hitter

(Skaggs wore No. 11 in HS)• Score 7 runs in 1st, 13 runs total

(Skaggs birthday is 7/13) pic.twitter.com/d5tb0yH5hD— CBS Sports (@CBSSports) July 13, 2019

This is not meant to chastise those who find these numbers compelling, or as proof of some divine intervention on a night that was charged with meaning for so many people, players and fans alike. Still, some perspective: Mike Trout’s home runs regularly travel 420 feet, 20th-best in baseball; that he hit one 450 feet off Mike Leake, whose 43.1% hard-hit rate is bottom 9% in the league, is not so surprising. The Mariners are in a rebuild and are so far down in the AL West Elon Musk is planning a high-speed transportation line to get there; that they would get no-hit at some point this season, especially as a combined no-hitter, doesn’t seem beyond the realm of possibility.

Of course, what’s significant is that they got no-hit on this night, a night that meant so much to the Angels and their fans because they needed it to, because telling ourselves a story about a tragedy is a way to round off the corners of it and smooth that grief into a pebble rolled in the hand rather than a stone in the shoe. Sometimes, you send emails off into space, and just hope to hear back.

Most people have never heard of Eddie Dundon. A quick Google search reveals some hits for our Eddie, but that’s not saying much. Finding someone’s name in a Google search does not mean they are well-known.

That’s a shame, because Eddie is instrumental to the game as we know it today. He wasn’t a good player, let alone a great player. He wasn’t an all-time great manager or someone who accomplished some amazing feat heretofore thought impossible. Eddie didn’t accomplish much on the playing field in his two major league seasons or in his many years in the minors, yet his impact is felt in every game that we ever watch.

You see, Eddie was deaf and a mute. When Eddie played in the early 1880s it was common practice for umpires to simply say whether a pitch was a strike or a ball. They didn’t make an out or safe gesture either, all they had to do was say that a player was out or safe and everyone understood. Except maybe they didn’t, because there were deaf and mute players before Eddie. It just happens that Eddie wanted to know what was happening to and around him during games.

Thanks to Bill O’Neal’s American Association: A Baseball History we know that Eddie is the person who convinced AA umpires to start using hand signals. The story goes that Eddie started gesturing to umps from the mound in the middle of games. He would coach them to understand what he wanted them to do until they started using hand signals to signify balls and strikes as well as out and safe calls. The hand signals caught on and soon made their way to the major leagues and then across the entire baseball landscape. Now, thanks to Eddie, deaf spectators could enjoy the game a little better and other deaf players could see the goings on around them.

To say that Eddie is important to the history of baseball would be an understatement. Of course, maybe Eddie never really did cause umpires to start implementing hand signals. Eddie is a figure of lore and others have tried to take credit for his accomplishment. Perhaps they are right and Eddie was merely relaying what he had previously seen?

Be that as it may, the next time an umpire makes a supremely demonstrative strike three hand signal, make sure to say a thank you to Eddie Dundon because someone deserves the credit for all those hand signals have given us over the years.

Joe: Wow, what an incredible Home Run Derby. Here comes the grounds crew to clear the field of the bats, balls, and bases, making way for the standing desks.

Tom: So people want to watch this, Joe? This is what the fans want?

Joe: Here they come, sauntering from the dugout, squinting into the afternoon sun: thirty of the best and brightest, one nominee from each team. Some come from Research & Development, others Analytics, still others from Research & Development Analytics. But regardless of their background, they all share that same passion for data-based decision making.

Tom: They’re wearing chinos, Joe.

Joe: As a reminder to viewers, each team is given a randomized list of 1000 fictional players with detailed, life-like profiles. They have ten minutes to evaluate and sort them into a 40 man roster. That roster will then compete in a simulated full season, with the winner of the World Series taking home the glory of Best Front Office and extra space towards their team’s salary cap.

Tom: You think this is their first time on a baseball field?

Joe: They are logging into their portals now. A hush has fallen over the fifty thousand fans here in Toronto. The clack of keys echoes through the stadium.

Tom: Hey Joe, can you tell us about what’s going on in the bullpen?

Joe: You mean AstroBot? I—yes. The human-computer hybrid designed with Trevor Bauer’s face, a computer’s brain, and Justin Verlander’s personality. They’ve put him in the bullpen, behind the fence. Last year he—and there’s the ding! We’re off. Look at those fingers fly.

Tom: What’s happening, I just see clicking.

Joe: Wow. On the big screen we can see Blue Jays’ Alison Moore just pulled up a data set of some proprietary bat-speed/swing plane metric. Look at that, she has nine Excel sheets open. Risky move. May cost her if she can’t synthesize that data fast enough.

Tom: The fans seem to be criticizing her height here, Joe.

Joe: I believe they’re chanting “Sort,” Tom.

Tom: Ah. OK, so walk me through the Orioles’ Fallon Jons strategy. It seems to be unique.

Joe: Definitely unique. We saw this last year as well. For the hitters, Fallon is sorting by bicep circumference. The pitchers he is sorting by star sign, effectively eliminating Libras all together.

Tom: I’m seeing a lot of snake references. Are snakes allowed on the field, Joe?

Joe: That’s Python, Tom. Don’t worry, there are some R’s out there too.

Tom: Righties, of course. The Rays and Mariners just swapped rosters, is that legal?

Joe: I think the Dodgers’ Antione Jordan has set up a deep neural network. Yes, and it appears he’s trying to decide what decay rate to fix for his ReLU. If he wants—

Tom: Sorry to interrupt but a pigeon just landed on the Mets’ keyboard and is pecking at the keys!

Joe: The Mets executives are yelling at their player not to interfere. Two years in a row. Amazing.

Tom: Wait. Joe. Where’s AstroBot?

Joe: What? Oh, God. It appears AstroBot has broken through the gate. He’s sprinting right at the Dodgers’ desk. No. No! He’s destroying the computers, desks are flying, people are fleeing for the exits.

Tom: Look at the spin rate on those desks.

Joe: Give it the prize! Give it what it wants! Give it [feed cut]

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now