Note: Our review of the ongoing theatrical production based on Toni Stone’s life can be read here.

One of the most striking vignettes in A League of Their Own is scarcely a quarter-minute long: a ball rolls away from Dottie Hinson, stopping near a well-dressed Black woman, segregated from the action (with a group of Black men and women) in a smattering of seats in right field. The woman watches the ball quizzically as its momentum arrests, then walks to it, fluidly picking up the baseball but waiting with it until Hinson (Geena Davis’ character) motions for the ball “right here.” The unnamed woman whips the ball back home, a strike from 200 feet that stings Hinson’s glove hand. She looks at the other woman as if in shock, and her gaze is met with a knowing smile.

The scene neatly illustrates the blind spot of the “league of their own,” simultaneously highlighting the glaring whiteness of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League and rebutting as spurious the notion that Black women who showed “promise of exceptional ability” were not evident in the years of AAGPBL’s existence (1943-1954). Of course, even had the league opened its rosters to Black women, no one was coercing Toni Stone into a skirt.

“Professional” was, to Toni Stone, always the sort of word which gleamed with magical possibility. “Her highest praise,” it was the sobriquet young “Tomboy” Stone appended to baseball cleats she saw in store windows, but her working-class family could never afford, growing up in St. Paul, Minnesota. Still, the glove Stone bought in her youth at a Goodwill for 25 cents stayed with her throughout her playing career just as well as the cleats former big leaguer (and baseball school proprietor) Gabby Street gifted her after her dogged determination to be afforded a shot wormed her way into his favor.

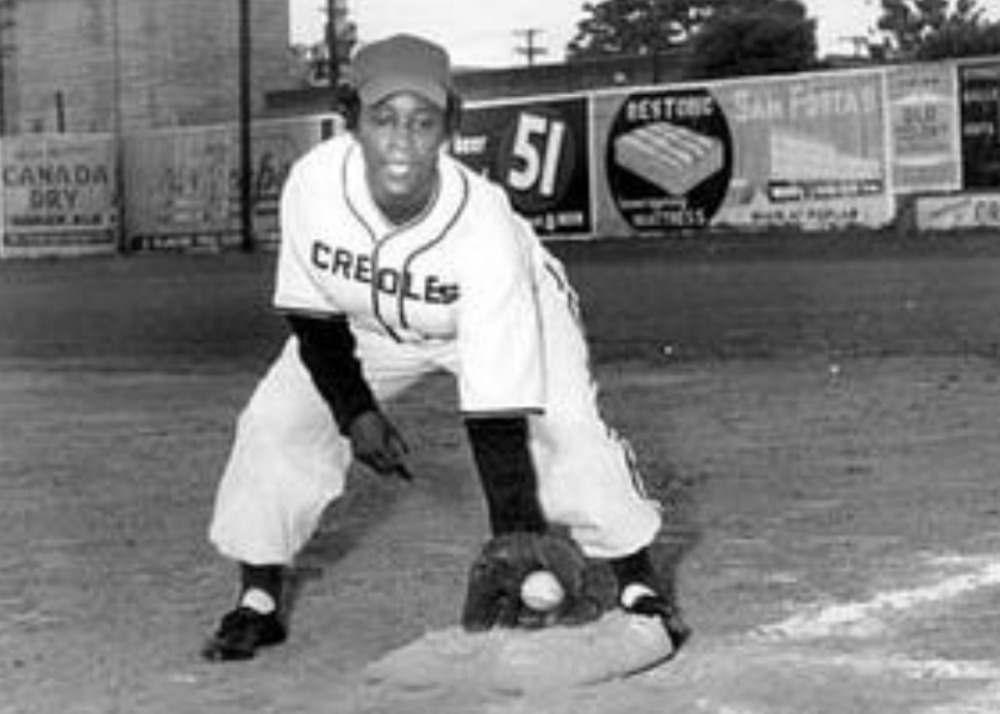

Despite her childhood association of articles of clothing, moreso than actions, with the notion of sports professionalism, Stone, in her two seasons (1953-1954) as the first woman to play men’s professional baseball in the Negro Leagues, exemplified the idea of a professional in both her indefatigable dedication and unflapping comporture. Particularly given her performance was described as “credible” in an environment not receptive to her inclusion or thriving, Stone’s utility as a player and the interest she sparked in fan bases raises the question of why no woman ever, as Stone hoped, played in the Pacific Coast League, or is even numbered among the thousands of men appearing annually in affiliated ball.

Stone’s genesis as a ballplayer recalls the origin stories of many American athletes from small towns in the mid-nineteenth century. The best athlete in her hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota (where her family had a generational footprint and moved in her 10th year), Stone’s realistically-oriented parents doubted that a girl could be a fiscally-successful athlete during a period in which few obvious role models existed. Even if they did not necessarily enforce the notion that “a girl going to play ball was a disgrace to society,” Willa and Boykin Stone were less than thrilled that their daughter was, despite every effort to encourage elsewise, determined to spend as much time as she could on a diamond.

Stone dominated seemingly every athletic enterprise she entered and quickly craved the higher competition she expected among boys. In her first such experience, Stone was revelatory on her Catholic church’s team, invigorating a lifelong interest in playing with the boys as well as the surety that she could succeed among them. Stone’s parents, strongly focused on their children, especially the girls, achieving financial independence, were skeptical of the uncharted path Tomboy — as she was known through her youth and adolescence — wanted to tread.

However, Rondo, the highly Black neighborhood in which the Stones and much of their extended family lived, was for its residents a place where “you could dream your dreams.” Even in the dire financial straits the Great Depression left many in, the families of the neighborhood were spared privation by collective effort: “house-rent parties,” continuous recycling of resources, and consistent patronages of Black businesses kept the neighborhood and its residents afloat. That Tomboy was so determined to give her dreams a real shot is less surprising in the context of her childhood.

When it became clear that the Stones’ efforts to feminize their child, always comfortable in dungarees and shirts, were having little to adverse effect, Willa sat down her daughter and told her “if people are going to talk, then give them something to talk about.” Talk they would, but despite the cruelties leveled at her throughout her extremely long playing career (while most of her post-Negro League experience appears limited to neighborhood games, Stone did not hang up her glove for good until she was 65 and her husband 100) Toni was never cowed.

In addition to the racial epithets commonly hurled at Black athletes of the period, Stone was called “bull dagger” (a racialized slur for a masculine lesbian) and was intimately familiar with the “back to the kitchen” song and dance. Stone wanted to play baseball and be treated as a ballplayer, nothing more, but could never be respected as such by the masses, even as they filled gates to watch the spectacle of a woman replacing Hank Aaron for the Indianapolis Clowns.

The inability of white men to relinquish unjustly-held ground they had denied to all but their selected few, of course, extended far beyond the various baseball leagues of the time. When Stone first moved to San Francisco (and adopted the name, Toni, that she used her entire adult life) she worked in a shipyard, and the abuse she faced there was a mirror of that which she would see throughout her career. Rather than accept that in keeping these spaces limited to white men they were closing themselves off to a vast docket of qualified workers, “many men believed women took away work that was rightly theirs and scrambled to keep the shipyards white and male.”

That both Jackie Robinson’s MLB debut and Stone’s for the Clowns were attended by writers prophesying the looming demise of the sport should emphasize that the basis of barring athletes from a sport is always resentment — personal inadequacy offloaded onto an uninvolved party.

Toni Stone continually held her own on the field, impressing with a patient bat, quick, trained hands at second base, and a rocket of an arm that Stone said Satchel Paige himself once commented on. We have, however, little in the way of complete and quantifiable statistics of Stone’s performance. The baseball Black athletes were permitted to play was given less attention than MLB, resulting in “flawed record keeping made it difficult to offer a quantitative argument that she played as well as the men, or that black players were as good as whites.”

The recorded batting averages from Stone’s Negro League seasons, first with the Clowns and then with the Kansas City Monarchs, were and will remain incomplete, because only league games were sometimes tracked, neglecting the many barnstorming efforts that padded a long season. The result is an incomplete record, for Stone, for James “Cool Papa” Bell, who once had five hits and steals in a game that was never logged, for the entire Negro Leagues.

That incomplete record only lends credence to Stone’s belief that “textbook history always boiled down to Captain-John-Smith-and-Pocahontas.” It’s a remarkably prescient statement from Stone, long before Disney’s Pocahantas and its inevitable (and inevitably horrifying) live-action remake. Stone understood that people are looking for the best story, not the truest one, or the realest.

Stone, a player who was the epitome of competence, competitive spirit, and resilience, is a phenomenal story, a remarkable life. This was a professional baseball player who was routinely denied service at hotels (that were themselves a selection of only hotels accepting Black clientele) run by proprietors who assumed she was the team’s sex worker. Only a person of uncommon wherewithal and gumption would, after such slights, form a network of sex workers who quartered and fed her and even assisted her in fashioning a bra that was more resilient against direct hits to the chest.

It was a network that supported Toni Stone’s relentless determination and led her to become the first woman in men’s professional baseball, and it will take a network to bring women back to professional baseball, six decades after they left. It’s time to think about how we construct that network.

Almost all of the information in this comes from Curveball: the Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, on which the Toni Stone play is also based and is considered the definitive account of Stone’s life.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now