Minnesota won the World Series in 1991 while hitting 140 homers and allowing 139 homers, out-homering their opponents by the slimmest of margins. Then, beginning in 1992 and extending through 2018, the Twins were out-homered by their opponents in 26 of the next 27 years, including each of the last 14 years. During that 27-season stretch, the Twins allowed an astounding 1,149 more home runs than they hit.

To put that in some context, consider that during the same span Ken Griffey Jr. and Manny Ramirez combined to hit 1,125 homers — 570 for Griffey, 555 for Ramirez — meaning you could have added both all-time great sluggers to Minnesota’s lineup for essentially their entire careers, without even subtracting anyone else to make room for them, and the Twins still would have been out-homered from 1992-2018.

Things have, uh, changed.

Not only do the Twins lead the majors with 224 homers this season, they’re on pace to shatter the all-time MLB team record for home runs in a season. That mark currently belongs to last year’s Yankees, who hit 267. This year’s Twins have 224 through 115 games, putting them on pace for 316. You could subtract Nelson Cruz‘s team-leading 32 homers and the Twins would still be on pace to break the all-time record.

Meanwhile, the Twins’ pitching staff, which was often every bit to blame as the lineup for the 1992-2018 out-homering, has allowed the majors’ eighth-fewest homers (146). Out-homered by an average of 42 per season from 1992-2018, the Twins are now on pace to hit 110 more homers than they give up this year, which would fall just short of the all-time record of +116 held by the legendary 1927 Yankees.

All of which brings us to the natural question: How the hell did this happen?

Let’s start at the top. In noting the Twins’ nearly three decades of being out-homered, it’s important to know that they had the same leadership in place nearly that whole time. Terry Ryan became the Twins’ general manager in 1994 and was fired following the 2016 season, with a hiatus from 2008-2011 during which one of his longtime assistants, Bill Smith, and the same group of longtime support staff, ran the team.

That changed in 2017, when the Twins replaced Ryan with two outside hires, bringing in chief baseball officer Derek Falvey from the Indians and general manager Thad Levine from the Rangers. Together, they set out to drag the Twins organization into the 21st century on and off the field, overhauling almost every aspect of the team. Minnesota was still out-homered in 2017 and 2018, but by “only” 18 and 32, respectively.

More importantly, even someone not following the Twins on a daily basis could tell that changes were afoot simply by looking at the stylistic makeup of the team. Twins pitchers, dead last in strikeout rate from 1992-2016, moved toward the middle of the pack in 2017-2018, as Ryan’s fetish for low-velocity strike-throwers was pushed aside. However, the most extreme changes occurred on the other side of the ball.

For decades, the Twins drafted, signed, developed, and traded for speedy, athletic, ground-ball hitters who put the ball in play. When that approach worked — roughly 2001-2010 — they stole bases, hit gappers, and played good defense behind pitch-to-contact staffs. When that approach didn’t work — roughly 1993-2000 and 2011-2016 — there weren’t enough infield hits and hustle doubles in the world to make up for that homer deficit.

Falvey and Levine spent the offseason adding veteran power hitters Nelson Cruz, C.J. Cron, Jonathan Schoop, and Marwin Gonzalez, and that quartet has combined for 79 homers and a .500 slugging percentage in 1,451 plate appearances. Hitting coaches James Rowson and Rudy Hernandez worked with the Twins’ nucleus of young hitters to attack more pitches within the strike zone and elevate the ball more often.

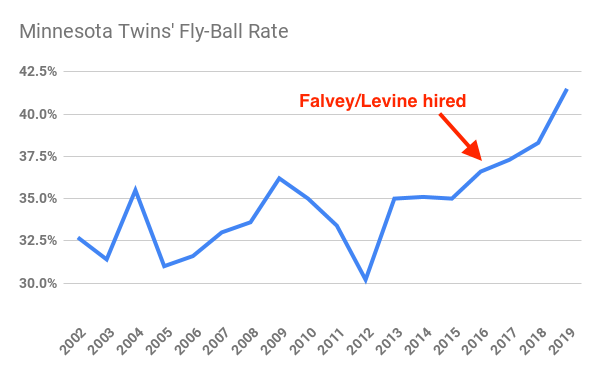

Detailed batted-ball data is available since 2002. Combined from 2002-2016, the Twins hit the fewest fly balls (33 percent) in baseball and ranked among the bottom three teams in fly-ball rate eight times in 15 seasons, including dead last four times. In the first two seasons of the Falvey/Levine (and Rowson) regime, they had the majors’ fourth-highest and second-highest fly-ball rates. And now in Year 3, they’ve hit the most fly balls in baseball.

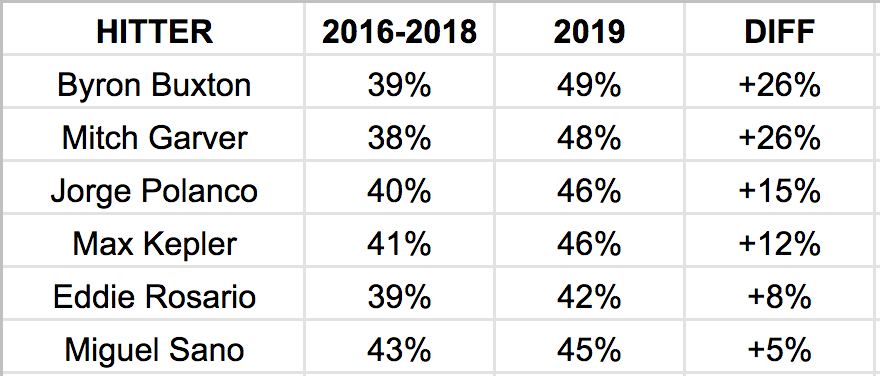

Some of that rapid increase in fly balls can be attributed to signings and trades targeting established fly-ball hitters, with Cruz being the prime example. However, the bigger impact came from hitters already on the team. Look at the dramatic increase in fly-ball rate for the Twins’ six core holdover hitters — Jorge Polanco, Byron Buxton, Miguel Sano, Eddie Rosario, Max Kepler, and Mitch Garver — comparing 2016-2018 to 2019.

As a group, those six 27-and-under hitters have upped their fly-ball rate by 15 percent this season at a time when the league-average fly-ball rate has barely inched up from 35 to 36 percent. Sano has been a homer-hunting fly-ball hitter since the Twins signed him as a 16-year-old, so his increase has understandably been the smallest, but the larger impact on Buxton, Garver, Polanco, and Kepler has been career-altering.

Buxton, who as recently as last season was being instructed to hit the ball on the ground in search of speed-fueled singles by since-fired manager Paul Molitor, now has the majors’ fourth-highest fly-ball rate for right-handed hitters, trailing only well-known sluggers Rhys Hoskins, Edwin Encarnacion, and Mike Trout. Buxton has a .513 slugging percentage, with 44 extra-base hits in 82 games.

Garver, a marginal prospect who slugged .428 in five seasons as a minor leaguer, didn’t reach the majors until age 26, and once seemed destined to be a backup catcher at best, now has one of the league’s 10 highest fly-ball rates and 10 lowest out-of-zone swing rates. He’s hitting .275/.358/.621 with 21 homers in 240 plate appearances, leading all major-league catchers in slugging percentage and OPS.

Polanco was a favorite of the previous regime, an athletic, skinny middle infielder with good contact skills. Rowson got him to start elevating the ball and now, like fellow diminutive, high-contact infielders Jose Altuve and Jose Ramirez before him, he’s added over-the-fence power without sacrificing bat-to-ball skills. Polanco started the All-Star game for the American League and has 17 homers in 107 games after totaling 23 in 288 games before 2019.

One of rookie manager Rocco Baldelli‘s first changes was installing Kepler as the leadoff hitter despite a .313 career on-base percentage. Baldelli felt that Kepler would boost his OBP — and he has, to .340 — but more than that he believed the 26-year-old was on the verge of becoming one of the Twins’ best players and wanted to get him as many at-bats as possible. Kepler is slugging .551 with 31 homers and leads the Twins in Win Probability Added.

Ultimately it’s difficult to divvy up exact credit among the Twins’ coaching staff, analytics department, front office bosses, and the players themselves, but that’s sort of the point. Falvey and Levine have created an organization where info and ideas flow freely from the top to the bottom and everywhere in between, which had been lacking for decades with the Twins and became an impossible-to-ignore weakness in the final years of the Ryan era.

They brought in fresh voices and parted ways with stale ones, they added veterans who fit the team’s new preferred mold, and they used technology, data, and coaching to change the approaches of the lineup’s core. What’s remarkable is that they were able to dramatically alter the makeup of the lineup, going from the most ground balls to the most fly balls, and from little power to the most homers of all time, without sacrificing strikeouts.

The same team that came into this year having been out-homered in 14 consecutive seasons and all but one season since 1992 now leads the majors in home runs, slugging percentage, and isolated power in what is the most power-driven season in baseball history. Their lineup also has the majors’ fourth-lowest strikeout rate, a rare combo typically reserved for truly elite, championship-caliber lineups.

It’s only mid-August, but the Twins’ next homer will tie their all-time record for a season, which has stood since 1963. In a few weeks, they’ll break the all-time MLB record for homers in a season. It’s about the craziest thing any Twins fan could possibly have imagined just a few years ago. Change can happen fast, if you let it. In the Twins’ case, it took three years to change three decades. Swing hard, in case you hit it.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now