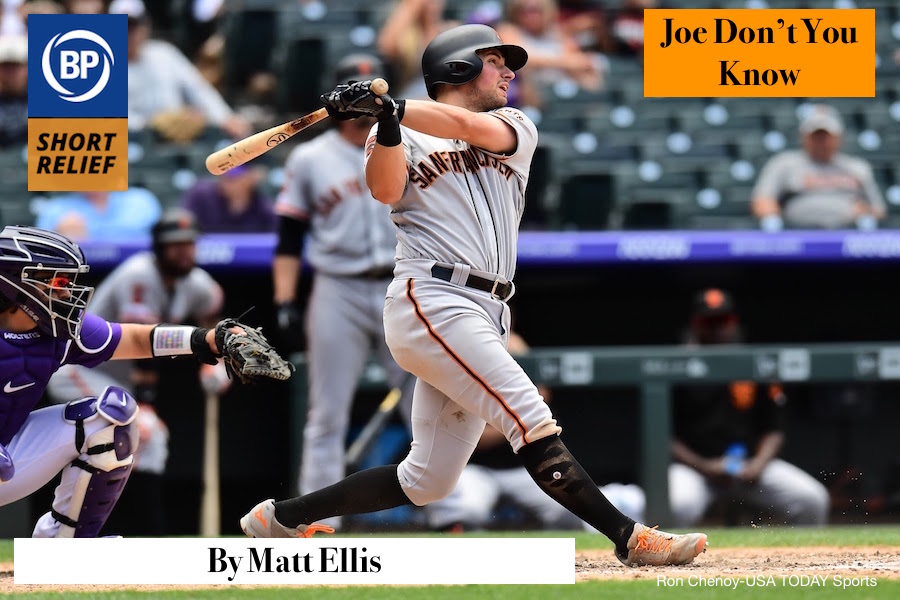

Joe Panik was DFAd by the San Francisco Giants yesterday. I can’t say that I really know much about Joe beyond any usual prospect-watch-young-star chronicle thing that could fit any other kid of his age (see: Brad Miller, Carlos Correa, Taijuan Walker, my hopes for a productive career by my early thirties, etc). But what I do remember are my friends on Giants Twitter regularly tweeting about him out of any context for my timeline in the upper corner of the Pacific Northwest.

I’d see something about “Panik!” that was a joke, because his name sounded like the word “panic,” which is funny. Another thing was that he really blossomed in those last years of the Giants’ odd-year dynasty thing. The good ones had Hunter Pence in-the-parkers and the bad ones had this kid stopping a ball from going out the infield, and sailing it to first down the San Francisco shipping line as if to say the place could have pride in its past and its future, because they were one and the same, regardless of the gentrification, poverty, and capital immiseration.

But the strangest thing about it all I think is that I didn’t realize that Panik hadn’t really been a productive baseball player since 2017, and his downward trajectory mirrored less that of growing pains than four thousand other twenty-something kids trying to cope with curveballs and lower body injuries. A typical case. In this sense, he is a shining example of the most pure Major League Baseball player in history. There are 329 members of the Hall of Fame, and almost 19,700 players who have ever had a Major League appearance. In the middle of that are guys who have put up three .4 win seasons and guys who have had one All-Star season before flaming out. Panik, truly, is the quintessential Major League Baseball player. A thing to truly be proud of.

Of course, this news will be met with any number of reactions. He will probably be picked up by someone, say, the Pirates, or maybe the Orioles, but he’s all but guaranteed not to look remotely like the flashy player that wowed America’s 21st Century capital in a 19th Century game. And it is those contradictions, together, that might help to illuminate exactly what is coming after, as players turn to numbers, as contracts turn to risk management, as surplus colonizes the immediacy of unknowing.

There’s another Joe Panik out there right now, and horrifyingly, he doesn’t know it. But he is, and he will, and we will again, and then there will be another.

There is a question I cannot answer. It’s haunted me for several months now. Every other baseball fan should answer easily, but I can’t.

On December 22, 2018, Effectively Wild hosts Ben Lindbergh and (at the time) Jeff Sullivan answered a listener email in episode 1312. The gist of the question is, “Would you rather watch baseball without reading about it, or read about baseball without watching it?” Lindbergh and Sullivan agreed: of course you should choose to watch baseball!

“You take the games,” responded Sullivan without hesitation. “We all get into this because of the games… All the other stuff is just noise. It’s designed to fill the gaps in between baseball games.” For the overwhelming majority of baseball fans, this is an easy decision. Even most statheads should agree that nothing beats actual baseball.

Except…I’m not so sure.

I am enthralled by the numbers and prose of baseball. Reading and thinking about the game is deeply, irrevocably attached to me. Falling into a Baseball-Reference rabbit hole gets me through a slow day. Refreshing Baseball Twitter helps me survive the agony of waiting in line at the grocery store or gas station. I would miss watching real baseball immensely, but I don’t think I could enjoy it as much without the context to which I am accustomed.

That I cannot answer this question begets more questions: What kind of fan have I become? Am I still a baseball fan at all? Have I become something else entirely? I could not imagine my life without baseball, but if I would choose words and numbers over games, I don’t know if I can call myself a baseball fan anymore, truly. Rather, am I a fan of a byproduct, intentionally choosing to assuage the symptoms over the affliction?

Further, if I am no longer a true baseball fan, what am I? Fanhood has been part of my identity since I was a toddler. What takes its place? Should I call myself a “baseball stats and articles fan” instead? That sounds ridiculous, though probably accurate.

Am I even qualified to consume the #content I hold dear? Should someone who is not a true baseball fan be allowed to analyze the game? Why should anyone listen to or read what I have to say on the subject of baseball, which I have inadvertently rejected for a lesser species? Shouldn’t you stop reading this right now?

These are questions I cannot answer.

According to one of those home DNA kits, I am half Viking and half Celt. You might take this to mean that I am a mighty warrior, fearlessly fighting endless battles in adverse conditions, blinding rain mixing with blood before being blown like ice pellets into my eyes by a freezing wind. And you might think me battle-crazed, perhaps even a little unhinged. You might be right.

But I think you might just as well assume that I come from people who were quite skilled at the art of fishing. The Welsh and Norse peoples both used a style of fishing called seine or seine-haul fishing, so called because of the type of netting used. A seine hangs vertically in the water, and can be used from boats or from the shore. For over 2,000 years, Welsh fishermen have taken seines out on wade-netting expeditions, the kind best suited for catching enough fish for individual households. Herring is a common catch.

The Vikings waded for their herring too. They also employed a dramatic method of fishing that used haaf (haf = open sea) netting. Imagine them at the Solway Firth in the Northern Irish Sea, ca. 950 CE. They are forming a line to carry a 16-foot net, and then walking into the water up to their chests. They are walking against the tide in order to catch salmon. The challenge is to catch salmon one at a time while not being swept away by the strong tidal flow.

The oldest known fishing net, found in northern Europe, dates to 8300 BCE. In other words, fishing nets have been around a long time, and they are still in use today, in every coastal region and on the open sea. We know how useful they are. Our 10,000-year relationship with them suggests that anyone can pick up a net and know what to do with it. They are easy to make, easy to deploy, and easy to use. Our species is comfortable with nets. They are long-term companions in our survival. They are everywhere. If you look around your house, you will find something made with netting.

Why not stadiums, too? Guaranteed Rate Field got netting, and Jeff McNeil used it instinctively. No planning, no practice, nothing but a deep strain of human DNA that saw a net and said, “A net! I can use that!” And it was so much fun to watch. Tell the truth, now. Didn’t you want to try it too?

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now