I grew up in a place where people worked hard. Most of the working men were coal miners, including my father and two of my uncles. The dads of almost all of my friends were coal miners.

In case there were any doubts about how dangerous mining was, when I was five years old the Wilberg Mine fire hit right around Christmas, 1984. It killed 27 miners who weren’t all that different from my father or uncles. It’s the first news story I remember being aware of as a kid.

The cadence of disaster at the mines was continuous, but not always predictable. There were the individual accidents that killed or maimed my friends’ fathers growing up, and then there were catastrophes. In 2007, the Crandall Canyon mine collapse killed nine workers and Central Utah grieved.

I was working two hours away when the news hit. I gasped with panic as my boss told me to go home and be with my family. I stayed at work, since all I could think was, “Go where?” My uncle worked in that mine and was part of the rescue crew. My father had left that same mining company to work for the Mine Safety and Health Administration as a trainer and was at the mine to work with the families. My mother was a registered nurse managing the emergency room of the hospital that would care for the injured. (The only hospital within 150 miles of the collapse.) I had nowhere to go. My family was working to do everything they could in the face of a community tragedy. If I went home I’d just be in the way of the work they needed to do.

Price, Utah is not a place that is unfamiliar with disasters.

All of this made the town simultaneously being taken hold of by opioids more shocking, even if in retrospect it was predictable.

It’s a town with no shortage of pain. While most of the writing on the opioid epidemic seems to focus on West Virginia, or Kentucky, Carbon County, Utah has a lot in common with those places. I remember the first rumors of people who were addicted to pills. I remember the shocking overdoses of people I knew growing up.

These days I often feel like I live a world away from my hometown. Chicago, Ill. is about as far from Price, Utah as any place in the United States. But when the news came out that baseball had lost Tyler Skaggs to opioids, I couldn’t stop thinking about home. These drugs ravaged my home town in ways that were as devastating as any mine disaster. And here they were again, in America’s pastime. I found myself wondering if coal miners and baseball players have more than we can possibly imagine in common.

On Friday, the Red Sox and Angels played a 15-inning game that lasted 5 hours and 23 minutes, making it the third-longest game of the season for the Red Sox and the second for the Angels. It’s no surprise these teams combined to produce less of a ballgame and more of an act of endurance. But what, exactly, happens to a person throughout the course of such a game? I’m glad you asked.

Innings 1-3: Excitement

A new day, a new game. Anything can happen! You’re just thrilled to exist in the world at the same time as baseball, the Most Perfect And Beautiful Of All The Things That We Should Feel Bad About Supporting.

Innings 4-6: Calmness

By this point, the game has more or less entered into a rhythm, and you’ve resigned yourself to it, allowing the familiarity and serenity of the game to wash over you. You’re no longer glued to the screen, taking time to fire off a few tweets or procure appropriate snackage.

Innings 7-9: Anxiousness

These are the most crucial innings of the game, the outcome of which rests almost entirely on the bullpen. You spend these innings willing your relievers to throw strikes, dammit! Every single pitch matters, which is reflected in your heart rate. You make a mental note to look up stress relief techniques before yelling for your team’s hitters to stop swinging at pitches above their heads!

Innings 10-11: Confusion

Still reeling from the events which led to extra innings, you’ve yet to re-focus your energy on the game. These innings barely count as extras, anyway, so by the time you finally become cognizant of them, the game could be over.

Innings 12-14: Ennui

The hours creep by, and you’re still watching for some inexplicable reason. Time is meaningless, and along with it life. You might never move from your seat on the couch, which is fine, because it’s as good a place as any to witness the slow decline of humanity until death mercifully claims you. Oh, look, a position player coming in to pitch, how novel.

Inning 15: Disappointment

If your team emerges victorious, relief creeps into you, but it’s mostly disappointment. You’ve wasted over five hours of your life watching a baseball game of all things, and no amount of coffee is going to mask the fact that you’re running on four hours of sleep and just dragged your sleeve through the puddle of drool on your desk. The only thing that would have made the sacrifice worth it would have been witnessing history — if the game is this long, it had better be the longest, either in innings to game time.

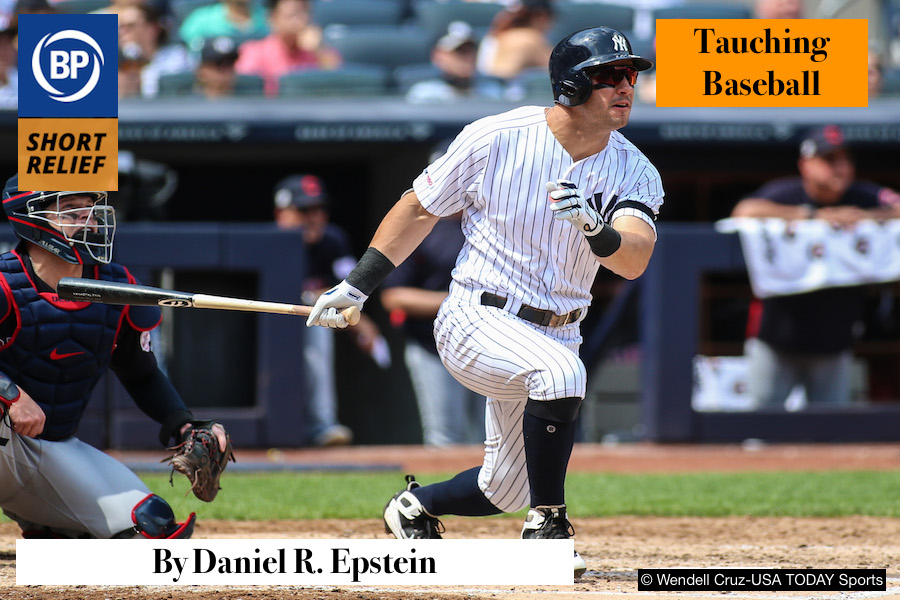

I have a friend named Mat who has taken an interest in baseball for the first time since we played together in Little League. He entrusted me to guide him through the baseball season, answering questions and explaining as much of the sport as I can. About once a week since Spring Training, we’ve waded through the ocean of children’s toys in my basement to watch the Yankees on my second-hand couches.

It’s a unique experience to teach baseball from scratch to a rational, semi-intelligent adult (I shouldn’t compliment him too much; he’ll probably read this). We can go directly from a nuanced labor discussion of the MLBPA collective bargaining agreement to, “What is Triple-A?” I’ve suffered several curricular dilemmas as well. For example, do I need to explain batting average at all, or can I jump straight to DRC+? What about everything in between, like OPS? There’s no syllabus here.

Our biggest teacher-student disagreement occurred on April 16th, when Mat selected his favorite player. The entire Yankee outfield — Giancarlo Stanton, Aaron Hicks, and Aaron Judge — was injured. They acquired some random Quad-A fill-in from Colorado at the end of March named Mike Tauchman, who was forced to play nearly everyday for lack of healthier options. He entered the game 2 for 16, but hit a home run and a double that day.

It doesn’t take long for even the most amateurish fans to become scouts. “This Tauchman guy is pretty good!” noted Mat. That observation set off hours of bickering, as I VERY CORRECTLY explained that even the worst players can have a good day. Tauchman was a blip on the radar who we’ll have forgotten entirely by July. He was indisputably NOT a good major leaguer. After all, I’ve been studying the sport for more than 30 years, and players don’t suddenly become stars at age-28.

Tauchman hit his second home run two games later, and another the following day. Mat and I argued via text after each one. By the end of the week, I was actively rooting against the starting left fielder on my favorite team, just to prove a point to my oldest friend. This drove Mat into a deeper love-fest with a player I was quite certain would fade into oblivion.

Of course I was wrong. Tauchman slashed .423/.474/.750 in July, and stayed hot through August.

In my quest to prove how VERY CORRECT I was, I forgot baseball’s one truth: none of us know anything. A person can spend an entire lifetime in baseball, and on their deathbed, the unknown will immeasurably outweigh the known. The only absolute is that as soon as we think we know something, we will soon be proven wrong. I am now aware that I know almost nothing about baseball. None of us do.

I could be wrong about this, or anything really, but I’m starting to think Mike Tauchman might be pretty good. Don’t tell Mat.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now