One important thing to grant yourself in these trying times is the freedom to like objectively crappy things. For me, this takes the shape of police procedurals, White Claws, hate-reading Money Diaries, and the MLB Draft.

To note: I’m not talking about the Draft as a concept here, although that is probably also crappy (I had a long discussion with some colleagues the other day about whether or not the Draft should be eliminated in favor of a full free-agency system, similar to IFA signings, in order to afford players more choice about where they live and work). But here I’m talking about the actual production of the MLB Draft, a truly terrible three-plus hours of television that I suck up every year like it’s the latest prestige HBO drama.

Everything about the studio production of the MLB Draft is bad. It takes place in a big boxy studio somewhere in the annals of the MLB Network with lighting design that wouldn’t be out of place at a Costco, if the ceilings at Costco were seven feet tall. The bright lights and general frenetic pace combine to give all participants the subtle sheen of a Christmas ball ornament grasped in the fist of a particularly sticky toddler. None of the actual decision-makers are in the room; instead, each team sends a representative to relay each team’s picks. I’m not even sure those phones are plugged in. And as a kicker, the best part of any draft — watching dreams come true, live and in real time — is largely absent here. Very few players are in attendance because, it turns out, Secaucus isn’t exactly a hotbed of baseball talent, and since the draft takes place in the beginning of June, most of the players are in class. That means the production leans heavily on a panel of 3-4 “draft experts,” 1-2 of whom have seen these players with their own two eyes, and one of whom is Harold Reynolds, who wanders from room to room demonstrating his karate moves. It’s borderline unwatchable. I love every second.

But the MLB Draft, one of my crappiest refuges, has been ruined for me, because now I have seen the LIDOM draft, and how are you gonna keep them down on the farm once they’ve seen Paris? Or in this case, Santo Domingo?

LIDOM is the winter league in the Dominican Republic, and holds a special place in the hearts of many Dominican-born players in MLB organizations, who wait anxiously to become draft-eligible (players are eligible for the LIDOM draft once they have been on an MLB organization’s full-season roster through August). Once drafted and given permission to play by their parent clubs — not something which will be granted to all players — players enjoy an environment that is much more familiar to them than the stilted relative silence of American baseball games. LIDOM fans are passionate, enthusiastic, and very, very loud; baseball stadiums are cultural centers on the island, and these players are at the center of it. So it makes sense, sadly, that the LIDOM draft has more in common with the NFL draft than the MLB one.

For starters, the event — which is held in something that is either a concert venue, shopping mall, spaceship, or some combination of all three–is hosted by Osvaldo Rodriguez Suncar, who brings an intensity that would burn down any American sports network. MLB Network found dead in a ditch!

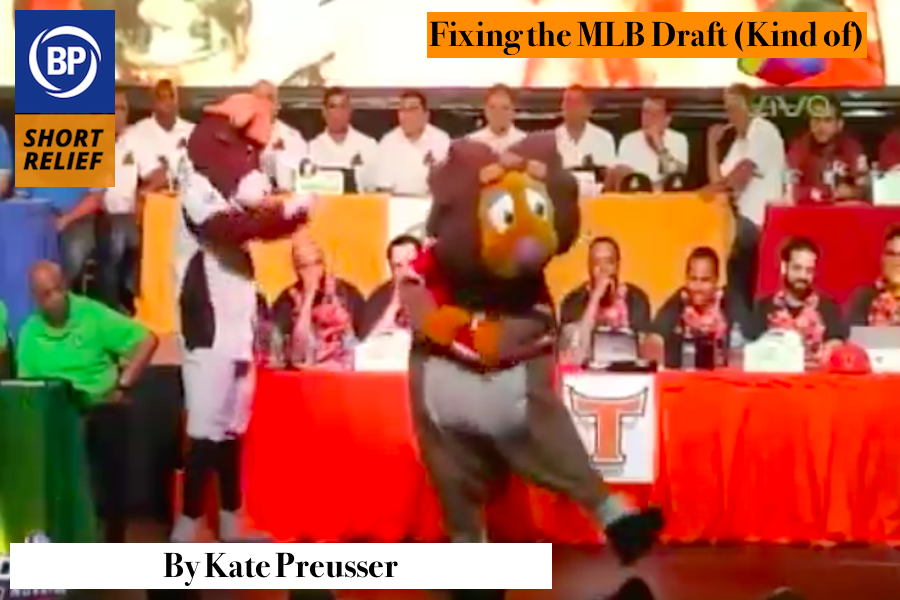

Next up, merengue dancers clad in each team’s respective jerseys and using baseball bats like Gene Kelly uses his umbrella in Singin’ in the Rain take the stage, where there is a special song for each team during which time that team’s mascot comes out and does a little dance, and then goes and high-fives all the team representatives, who are sitting on the stage as well, wearing their teams’ jerseys. Note these are not figureheads: these are the club’s top executives, scouts, and coaches, who are debating in real time who they will select.

The spectacle concluded with the merengue dancers each waving their team’s flag beneath a giant flag of the Dominican Republic while all the mascots danced together to a song with the lyrics “we won, we won, my team has won” over and over again, which is honestly no less annoying than “Go Cubs Go,” while a giant flaming baseball rotated slowly on the big screen behind them. It is my religion now.

Then it was time for a rundown of how the draft works, WWE-style introductions of each of the teams by Suncar, who is constantly set at 11, a DJ break (oh, yeah, there was also a DJ on stage spinning tunes), introductions of the commenters who would be analyzing each pick, and a quick pan of the players themselves, many of whom were in attendance. The president of LIDOM also gave a stirring introductory speech about the country’s love for baseball and advised each draftee to honor the DR’s rich baseball tradition by working hard every day and playing with passion. Word has it Rob Manfred saw it and immediately turned in his resignation and moved to Timbuktu to contemplate new life choices.

From there, things progressed mostly as we’re used to, with pre-recorded introductions from players who weren’t able to attend the draft (like the Mariners’ Julio Rodriguez, the fourth overall pick, who was in Arizona, where he’s preparing for the AFL) and jersey presentation to players who were there, interspersed with commentary and a few more DJ breaks. After some exit interviews where a representative from each team talked about their draft strategy, the show ended with more dancing, this time beneath a confetti cannon.

Look, there are some clear advantages LIDOM has vs. the MLB Draft. With only six teams, things move quickly, and the relatively small pool of players (158 this year) means the commentators are well-familiarized with almost every player. But the level of engagement and excitement for players who will only play three months for their teams is remarkable, and shouldn’t be hard to replicate considering MLB teams are drafting players for what’s possibly the bulk of their baseball careers.

All I’m saying is, a confetti cannon isn’t that expensive, Manfred. Get on it.

So much of my consumption of baseball over the last three years has been a process of reducing the sport—the batted balls, strikes, and swings—into numbers. Statcast and Gameday now break apart the complex physical interactions in real time and spit out statistical truth: that double was lucky, that lineout unfortunate, that strike, actually, a ball.

I process these half-digested numbers like a starving, infant bird, feeding the neurotic, pattern obsessed feelings-computer that is the human brain. The same brain that only survived the trip from the cave to the fruit tree by separating the flora and fauna into a series of safe/not safe, help/harm categories; all to find the outlier, that rustle in the bushes, that flash of unusual color that may be a tiger. The brain avoids these unplaceables because if left unplaced, it might eat you.

Baseball for me now is a jungle I want reduced and categorized so that I can trace the causal links far enough back that if it doesn’t fit, it gets researched until it does. It feels, at times, a genetic imperative.

And yet.

On Sunday, Yordan Álvarez hit a baseball so hard and fast it tore a nine inch gash into the delicate fabric of spacetime, rocketed through undiscovered corners of our universe, met the cast of Interstellar, and then relanded in the third deck at Minute Maid Park. It took 6.1 seconds for the ball to land, or 9.84% of the amount of time it takes for Minute Maid to make their lemonade.

The announcer declared it was “one of the longest home runs in the history of this ballpark.” And who could deny that? Watching it you could tell it landed in a place baseballs had never traveled before—the Mars of the ballpark, unbreathable, uninhabitable.

I eagerly awaited the Statcast data, expecting to learn a record had been broken, 700 feet I would have believed. I read it: 113.5 MPH, 36 degrees, 416 feet. They were wrong. It wasn’t the furthest ball anyone had hit at Minute Maid. It wasn’t the farthest ball anyone had hit at Minute Maid that game. Innings before, Álvarez himself hit one farther. My excitement waned.

Fans on Twitter declared Statcast broken or simply wrong. 416 feet? If hit into San Francisco’s Power Alley it would likely have been caught. An out? It was impossible to believe. The data didn’t fit.

I sat back. I felt cheated, like a kid, sick in bed waiting for the thermometer to confirm my imminent demise only for it to declare my illness racked body a healthy 98 degrees.

Our brains are computers obsessed with the processing of information. But what I like most from sport, why I turn it on, is it allows me to feel the things I am scared to feel in other places: wonder, confusion, awe. This is not the wild, not the jungle. Baseball is a safe place for me to say “I don’t understand that. I don’t understand how that’s possible.” Sometimes I want to close my eyes and wander into the bushes.

In 2001, the Brooklyn Cyclones were up one games to none in the best-of-three New York-Penn League championship series when the calendar flipped to September 11th. The rest of the series was cancelled. The Cyclones were awarded a co-championship with the Williamsport Crosscutters in their inaugural season.

18 years later they had yet to win a title all their own. During that time I mostly continued to live a ridiculously close six Q-line train stops away to a ballpark hosting an affiliate of a major league baseball team and rarely took advantage. I mostly treated KeySpan Park, later MCU Park, like I treated any other New York City landmark, never forgetting they existed but never ranking them any higher in priority than my own home.

Besides, there was The Incident. In either my first or second time at 1904 Surf Avenue, probably in the year 2003, I looked at the roster of the baby Mets and thought to myself, “Interesting. Some of the players are younger than I am.”

Younger than I am.

Younger than I am.

Younger than I am.

Younger

Younger

Younger

Younger

Younger

Youn

After the Cyclones won Game 1 of the NYPL championship series on Sunday, I didn’t really have much of an excuse to not attend Game 2. The price of a ticket, three rows from the Cyclones dugout no less, cost less than the round trip on the subway rides to the games. I didn’t get to see a team I supported win a championship in person for the first time in my life that night, but I did get to see a lot of disappointed young adults in their early twenties! As seemingly Cyclone after Cyclone struck out in the later innings, my eyes were on them slowly returning to the dugout while their eyes were fixated on their cleats. It’s likely they had never disappointed anyone this acutely on a baseball field before in their lives. I felt like I was intruding on a private moment. The lone highlight of the evening was spotting Sandy (jersey number 32, naturally) covering his eyes with his wings and shaking his head after one of those soul-crushing strikeouts. The seagull mascot was standing in his perch so to speak, preparing for the upcoming T-shirt toss. I was likely the only person out of the 2,499 who happened to be looking at Sandy at that moment, but Sandy was still performing. That is dedication, and/or muscle memory.

For Game 3 I sat farther away from the field, rows deeper than my ticket indicated in fact, on the side of the visitors’ dugout, as if I wanted the option of feeling detached from the potential loss. I kept a ton of notes on my phone throughout the night, but here were the truly important moments:

Jake Mangum’s walkup music was “Your Love” by The Outfield, and during the game I figured out “Your Love” is the Elizabethtown of music.

19th round draft pick and University of Houston’s all-time home run leader Joe Davis, a large, meaty young man, called “Chubby” by a Cyclones fan the night before before the fan googled to see if Davis wasn’t really 30 years old, was a few feet away from homering in the first inning to give the Lowell Spinners what would have likely been an insurmountable 3-0 lead, considering how games in that short-season Single-A league tend to go. A pitch or so later he tapped into a 6-4-3 double play to end the inning. I watched Davis as he methodically walked to meet a teammate halfway between his position of first base and the Spinners dugout to receive his glove and hat, in a profound daze, looking as if he just watched the house him and his high school sweetheart just finished paying the mortgage on explode (losing his favorite hat in the process), and figured he had to go somewhere, but had no specific place in mind, and wouldn’t for awhile.

Davis snapped out of it and almost homered again, this time in the 6th off of highly-touted Met prospect Matthew Allan, but the slight wind decided to drop the baseball off at the warning track.

The Cyclones actually won the thing. It was the first professional sports title won by a Brooklyn based team since the Dodgers won the 1955 World Series, to the possible chagrin of Kevin Durant. “We brought the championship to Brooklyn, so have a good time!” manager Edgardo Alfonzo shouted to his audience of almost 500 fewer fans than the night before. The Dodgers clinched their seventh consecutive NL West title just about 30 minutes later.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now