Big-league pitchers, at least in our current environs, are a little like Formula 1 cars: Powerful, complex machines boosted or derailed by adjustments that totally elude the naked eye, differences that strain the powers of comprehension even for those with a carefully calibrated knowledge of the mechanics of it all. As our ability to measure pitchers’ every move was hurtling forward, the ever-escalating zoom of our collective microscope seemed destined to bring everything into sharper focus.

I naively expected this, in its evolved form, to produce something akin to math. Slider X sits at Y position on the curve, and therefore should be used like Z. In reality, what it conjured was a very specific type of physics — an endless, inestimable subject cyclically explained and re-mystified by the pure, tangible numbers we can hold in our human heads. Pitching, in other words, is still designed to break us. Now it just does the deed with fancier gadgets and gizmos.

To the extent I have a tradition on my baseball writing calendar, it is to find a pitcher at the end of each season who seems to confound the general laws that govern major-league mounds. This has led me to study Jack Flaherty, the Cardinals ace who — having locked down the NL Central crown with his 10th start since Independence Day involving seven or more innings and one or fewer runs — has apparently reached stasis at a rare, blinding level of excellence.

Beginning with his final pre-All-Star start on July 7 (a loss in San Francisco), Flaherty has thrown 106 ⅓ innings and allowed 12 runs. Astros starter Gerrit Cole, simultaneously setting all-time records and making a compelling Cy Young case, has allowed 12 home runs over the same time period. After looking like “fairly promising 23-year-old starter suffering from the same homer problem as everyone else” up until July, something clicked and Flaherty became the most effective pitcher in the world.

What exactly clicked is harder to pin down. Flaherty is throwing the same pitches. And using them all at rates within five percentage points of his first-half self. At virtually identical velocities with mostly miniscule movement differences.

Even as recently as 2015, when Jake Arrieta achieved critical mass, it felt like there were only a half-dozen or so knobs on the control panel, and the Cubs had smartly ratcheted up his sinker-slider levels to Mach 7. You saw the particles shift, the patterns change. Flaherty’s transformation seems to have been orchestrated from something more akin to the NASA control room. Some levels were adjusted, a couple buttons were pressed, but a combination almost indistinguishable from the April through July 2 version of Flaherty (4.90 ERA) produced this? That’s how we land in the realm of the theoretical.

***

It’s always been this complicated, mind you, the amalgam of motion and friction and light that is pitching. Now we can just point to ever deeper explanations for that tenth of a point of ERA or that bump in strikeout rate.

Explaining Flaherty’s second half seems like it should be obvious. There should be a big thing. There isn’t. Not really. There is simply a collection of differences to be spotted from early July on — traced in the likely futile hope of understanding the larger effect.

His curveball got sharper.

The most noticeable repertoire change came on Flaherty’s curveball, which became a more vertically tilted pitch. The pitch was more of a bendy slurve earlier in the year, predominantly used to steal strikes against the left-handed hitters who saw him better — which, good to have, but not a world-beating offering. When deployed as a put-away pitch or alluring chase offering, it was middling at best. Here’s one early-season case where it works.

That’s not usually going to induce a swing. But these — after a transformation that was literally “an inch here, an inch there” — will do it, and did with great success. Hitters whiffed on 30 percent of their swings at it early on, then on more than 48 percent of them after July 7.

Did the extra bite allow for the pitch to be thrown lower more often? Or did the desire to get those swings further from harm’s way precipitate the tweak? Hard to say.

He threw his breaking balls lower.

See, since it’s 2019, you have probably already gathered that one major ingredient of Flaherty’s ungodly second half has been premium homer prevention. In the first half, the people hitting homers off of him did so from the left side — 11 of the 19 he allowed prior to that July 7 turning point were to lefties (which translated to a 2.4 HR/9).

But the curveball he changed wasn’t giving them up, anyway. Nevertheless, what he did was ramp up the use of his slider against lefties, and he threw that lower and out of the zone more, too. In fact, July, August were the months with the lowest and second-lowest average slider locations of Flaherty’s career. The Cardinals may deserve some institutional nod here. Miles Mikolas and Dakota Hudson also put more of their eggs in the low breaking ball basket down the stretch.

Flaherty’s slider, which was blasted for 6 homers prior to his turning point, has only surrendered one since, and there’s no real hint of movement change.

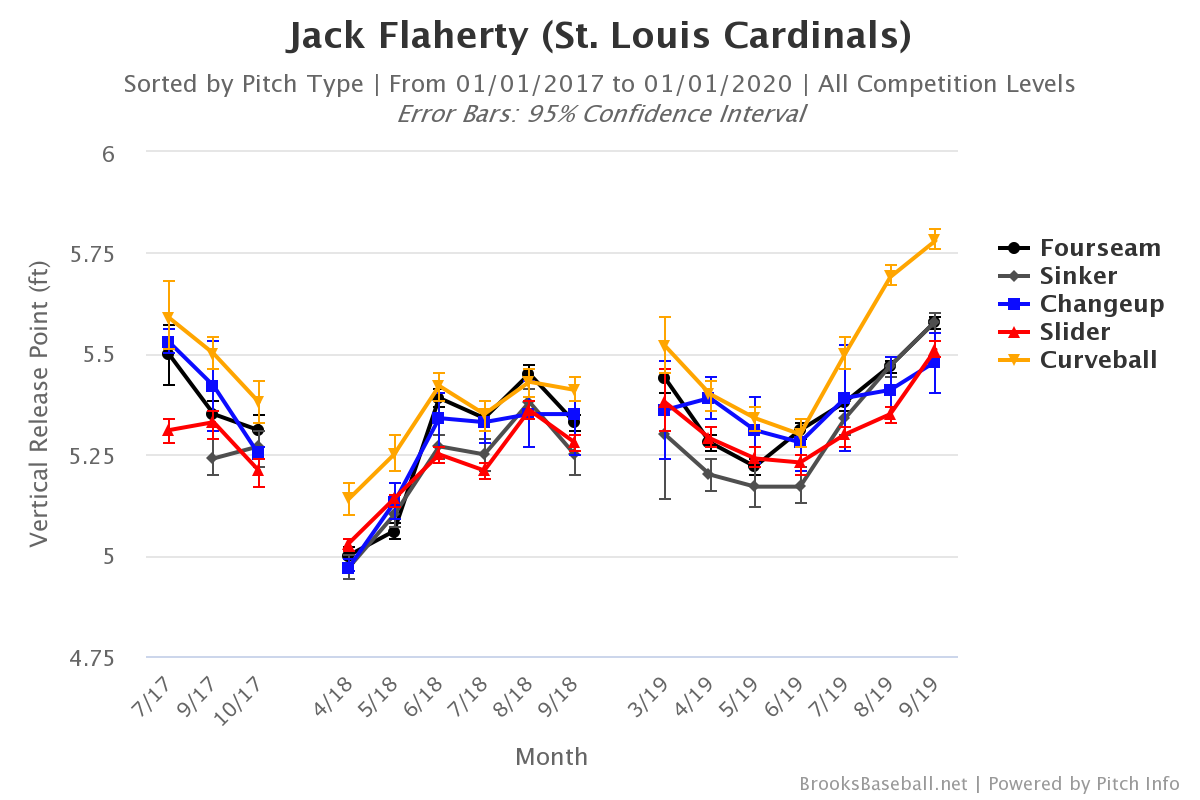

His moved his release point up.

It could be, however, that the two spiky offspeed attacks are playing up because of where they are starting from. Flaherty is releasing the ball more over the top and closer to his body than ever before, and the switch coincides with his emerging dominance.

At one point, it was reasonably theorized he may be best off lowering his arm angle closer to that of Max Scherzer, whose windup and arsenal are similar enough to think of as a model. Maybe Flaherty was even trying it early on, only to veer the opposite way.

Early on in Flaherty’s second-half run, a baseball-writing friend noticed that the curveball’s movement had become “visceral.” The description fits that curveball all of a sudden (as Ryan Braun would apparently tell you), and even though he didn’t change that pitch’s role, it’s hard not to see it as some form of key with it having been the most dramatically new piece of his stellar summer — a new thing to occupy hitters’ minds that also helped remove their focus from the fastball and the slider.

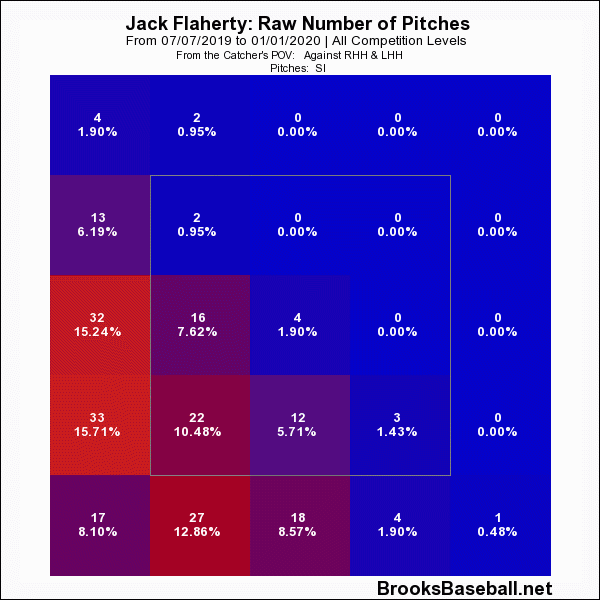

Also, sinkers.

Who knew?! A sinker in the contemporary game. Kidding, there are plenty about, they’re simply falling out of style. Flaherty, though, has boosted his sinker usage during his hot streak, especially against those lefties and to claw back in counts.

He appears to have impeccable control of it to the arm side. That location flummoxes right handers in ways that can actually produce whiffs (on a sinker!), but allows him a release valve for poor contact with lefties. Like so.

Unsurprisingly, the pitch (allowing a .182 slugging percentage overall in this stretch) has helped him keep them on the ground. Since July 7, he’s inducing a 46.7 percent ground-ball rate against left-handed hitters, after it had sunk to 35.8 percent in the homer-happy early part of the season.

In total, the miniscule changes have amounted to a conventional-looking powerhouse. Fastballs set up two different diving breaking balls that hitters can’t keep themselves from chasing. Maybe maintaining the general effect — if not the sub-1 ERA — is as simple as maintaining the new release point. Maybe something currently taken for granted will wrench the wrong way and mess it all up tomorrow.

This is pitching in 2019. It was always pitching, just as Earth was always 93 million miles from the sun. But now we know that. We know not only about the shape of these peak performances, but about ways to get there. We can look around. We can see everything that isn’t peak performance, see how far away it is. Yet we still get lost in the incalculable number of reasons why so-and-so cannot traverse the distance to the Jack Flaherty orbit, the one everyone wants to experience for just a little while. In this way, we are really just learning what a long way we have to go. And I, for one, am glad we don’t feel all that much closer.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now