I really wanted to be right. “It’s nice to be right,” says Meg Rowley, “but it’s also nice to be delighted.” This is true, but sometimes you are both wrong and undelighted.

It happened while I read this year’s vintage of Clayton Kershaw postseason postmortems. As I waded through the accusers and the apologists, the Wilts Under Pressures and the Small Sample Sizes, I developed a theory.

One of my pet theories is that everybody has their own pet theories. Everyone’s got a suspicion or a hunch about the way the world works. For confirmation, I texted my brother and his wife.

- “Ashley’s mom thinks terrible drivers are more likely to drive Volvos.”

- “People who own birds are weird. But I feel like that is a known one.”

- “So you know how some people say they have a cat that acts just like a dog and is friendly and greets you? Bobbin thinks those people are full of shit.”

Theory proven. It is indeed nice to be right.

My theory: Clayton Kershaw struggles in the postseason because he is always asked to pitch on short rest. Short rest is a desperation move, and aces like Kershaw are only asked to risk it because they’re so good in the first place. At the biggest moments we move the goalposts on them. Then we judge them on this very uncertain thing that, for fear of injury, they have never practiced. It’s like saying, “I noticed that you type a hundred words per minute, so tonight you’re playing keyboard in my band. Please wear fingerless gloves.”

I can math. Not to brag, but I took one semester of statistics in college. And sure, that was the absolute minimum math requirement for graduation. And sure, I spent much of the actual class time doodling in Microsoft Paint.

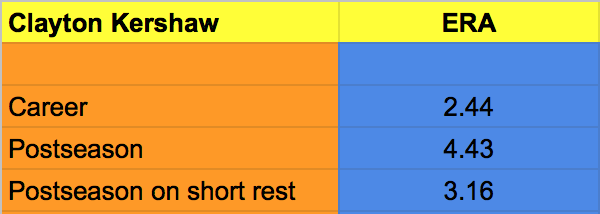

But I probably paid attention at some point. So I downloaded Kershaw’s stats and I mathed.

Uh-oh. What about appearances following short rest outings? What about WHIP? That’s a better indicator anyway. Maybe his WHIP on short rest is — wait, it’s better? Clayton Kershaw, future Hall of Famer despite his playoff performance, has a worse WHIP during the regular season than he does on short rest in the playoffs?

I diced the numbers every different way I could think of (so roughly three different ways). My theory was dead. Kershaw has simply pitched worse in the playoffs. True, he’s also been unlucky — he outpitched his ERA by a run and his fly balls went for home runs much oftener — but there’s no smoking gun, no easy culprit.

In her book Being Wrong, Karen Schulz wrote, “Like most pleasurable experiences, rightness is not ours to enjoy all the time.” She makes a good point, but I wasn’t in it for the pleasure. I liked my theory because it seemed humane. It’s easy to tear someone down. Postseason narratives are so quick to appear and so hard to shake. I want a neater answer than small sample size and statistical clustering. It makes me sad to think that a couple big mistakes will tarnish the reputation of the greatest pitcher of this generation. Even worse is entertaining the notion — which I still don’t buy — that Kershaw just can’t handle the pressure. But I’m all out of theories.

Gleyber Torres awakens in an alternate universe. In this new, unglamorous realm, the 22-year-old is no longer a star for the mighty Yankees. Instead, he’s traded his pinstripes for the trappings of a standard early-20s existence.

Swimming in debt and unshakable ennui, Torres climbs out of his partially deflated air mattress and rubs his eyes. It’s 10:48 am on a Tuesday. In two hours he will start his shift at the neighborhood coffee shop before a night of making Postmates deliveries. The gig economy, set to the soundtrack of coffee grinders and Torres’ curated Mitski playlist, is a much more humbling way to make a living than playing second base in New York.

Torres digs up his trusty laptop. It’s the same one he’s had since junior year of high school, and today it’s buried beneath stacks of pizza boxes and the only towel he owns. Torres pulls up Google and types “What grad schools are good?” Maybe, he thinks, this life of debt and burnout can be rectified by more debt and more overexertion.

Torres gets a text. It’s from a romantic partner that he met in an Uber pool. They’ve never hung out in the daytime, and after two weeks of late-night meetings, Torres has just learned their last name. “I’m moving to Austin,” the text reads. “My cousin had to kick one of her seven roommates out because they wouldn’t stop brewing kombucha in the garage. Sounds like they’re fully cancelled. But I get their room!”

Torres, dejected, reaches for his phone. The cracked screen carves a banana-shaped cut into his skin. Sucking his thumb to stop the bleeding, Torres summons the App Store and punches in “Tinder”. He sets the age range up to 35, because despite his youth, Torres has been feeling very mature, and not only because he can finally drink wine without immediately falling asleep. The first potential love interest is a 33-year-old corporate sales manager.

Their bio is a simple one-sentence instruction: “Swipe right if you have a good credit score”. Torres, who ditched a physical wallet in favor of a cryptocurrency and Venmo-based financial strategy, doesn’t even fully understand how credit cards work. Back to Google, this time to search “Credit scores that make you sound rich”. He settles on the message “What’s your favorite Philip Roth novel?”, hoping to reveal his sophisticated intelligence.

Only 90 minutes until work now. This gives Torres, he figures, enough time to either knock out a few small tasks (join DSA, go viral, place a bulk order for Top Ramen, buy second towel), or one big one (start a podcast, apply for jobs with healthcare, find an apartment with washer and dryer). The mere act of looking at his to-do list feels like a completed chore. Torres decides he’ll get to this tomorrow, and plops back on the air mattress for a well-deserved nap, dreaming of a life where he actually cashed in on his early trajectory as a promising, gifted child.

The Yankees have reached the ALCS again — their twelfth ALCS appearance since 1996. It’s hard to imagine nowadays, but before the mid-90s, they were a subpar team for a long time. As a Yankee fan born in 1983, the 1996 team was the first in my lifetime to make an extended playoff run, ultimately winning the World Series. But the ALCS was especially memorable because of such an unlikely hero.

In Game One, the Orioles led 4-3 in the eighth inning. Up-and-coming shortstop Derek Jeter slapped a lazy fly ball to right field. It would have been an easy out in any other ballpark, but in Yankee Stadium it chased right fielder Tony Tarasco to the warning track. He camped underneath, but the ball never reached his glove. Jeffrey Maier, a 12-year-old Yankee fan, reached over the wall and scooped the ball into his lap. The umpires incorrectly ruled it a home run, and in the days before replay, the game was tied. The Yankees ultimately won on a Bernie Williams walk-off homer in the eleventh inning.

Maier became a celebrity, and in a way he remains one. The video clip of his home run snag will remain rotating through Yankee highlights forever. He even has a Wikipedia page. He’ll always be the 12-year-old boy who saved the Yankees’ postseason…

Except he’s not 12 anymore. He and I were born in the same year. Just as I’ve grown up and lived my life, presumably so has he. I’m not going to Google him; he’s no longer a public figure and is entitled to privacy. He’s an accountant, or a teacher, or a pilates instructor. He’s married with three kids, or single, or “It’s complicated.” He lives in Queens, or Iowa, or Mongolia. He’s 35 — growing, changing, and learning — yet still forever 12 at the same time.

If you had to be stuck at a certain age, hardly anyone would pick 12. You’re no longer adorable or innocent, and you don’t get the benefit of the doubt. Hormones are firing for the first time, and you have no idea how to handle that. You’re not old enough to do much of anything independently. Right at the age when you start to care about physical appearance, you have to start changing into gym clothes for P.E. Also, you can’t master your locker combination.

I am 36, and I don’t know if my life has peaked yet. My best days might or might not be ahead of me, but at least I have that opportunity. When Maier stole that home run for Jeter, he robbed himself of possibility. No matter what path his life takes, he’ll be best remembered at 12. Can you look back at your 12-year-old self with fond recollection? Would you want to be judged, positively or negatively, for your preteen actions? Probably not, yet he must live that way for the rest of his life — growing older every day, and permanently 12.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now