I was talking to my sister a few weeks ago about the likelihood of Mookie Betts being traded in the offseason. She was sad about the prospect, of course, but she said that it wouldn’t be devastating. When prompted for an explanation, she brought up his end-of-season comment in which he stated, “That’s out of my hands. I have my representation to take care of that type of stuff so I don’t worry about it.” She declared that this statement irked her because it demonstrated a lack of loyalty to the franchise. Her ideal roster, she said, would be filled with players who contributed as much passion to the team as she did, regardless of their skill level.

I’m sure she is far from alone in holding such a belief, because professional baseball players have for decades acted as more than mere employees. They occupy a particular space which both lends itself to community involvement and expects it of them, giving credence to the argument that playing professional baseball is a privilege rather than a right.

On one hand, this is correct. Their job necessarily puts them in a position of prominence within communities, affording them a unique closeness with fans, and anyone who occupies such a position should be expected to help those around them in whatever way possible. Charitable work should be seen as both a privilege and a duty, and for many players it is both of those things.

But being in a position where it is expected of one to forge close bonds with particular communities comes with a particular set of drawbacks. For one, it exacerbates the common belief among fans that we hold some amount of ownership over these players and they in turn owe us something. Because these players are expected to integrate themselves on some level into our communities, we begin to close the gap between player and respective city, projecting our likes and dislikes, our values, onto them. Because we identify so heavily with where we’re from and our favorite team, we start to expect the same of the players, and so when they choose to leave or voice anything other than undying love for their current team, it feels like a betrayal.

Forging this imagined relationship between fan and player serves the purpose of leveraging the *actual* player-owner relationship in favor of the owners. Because owners are seemingly more entrenched in the community due to appearing to have invested in it in some way, fans are more predisposed to believe them loyal. We’re tricked into thinking that we’re on the same team as the owners because we feel like we’ve also invested in the team. And so players become the odd people out, the ones who do the most investing and receive the least sympathy in return.

Some jobs come with a great number of privileges, but at the end of the day, they’re just jobs, and demanding loyalty without actually offering it ourselves only serves to make the job of playing professional baseball that much less attractive.

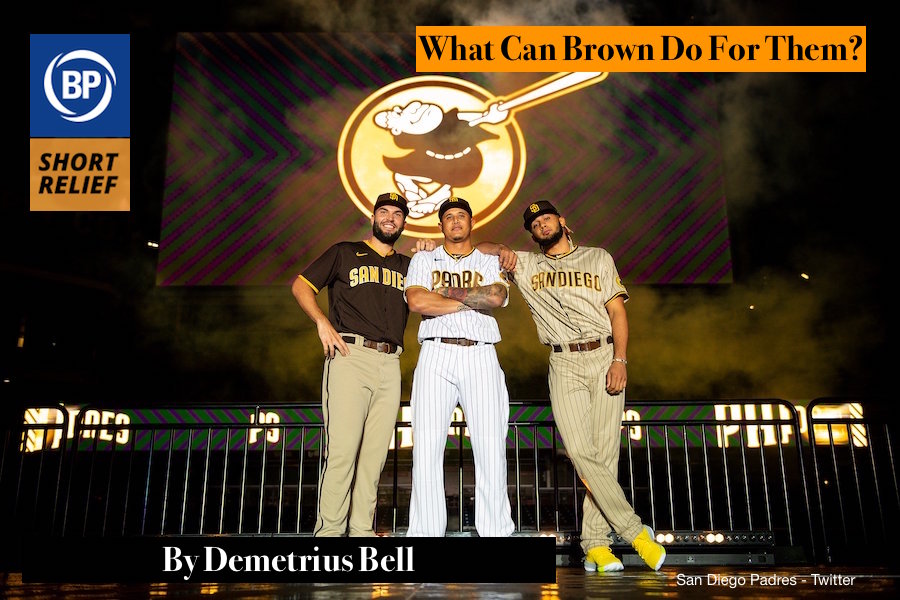

In 1985, the San Diego Padres made a grave mistake. Off the heels of winning the 1984 pennant, they made the ill-fated decision to eliminate the gold from their color scheme and become a strictly brown and orange team. This travesty was possibly the fault of Steve Garvey, who upon putting on his Padres jersey for the first time allegedly whined that he resembled a taco. The club not long after agreed to the jersey designed by the same firm that gave the San Francisco Giants a new look for 1983, making the Padres look remarkably similar to their in-state neighbors to the north. This was the beginning of their descent into logo and uniform boredom.

By 1991, the Padres had replaced brown with blue, and that change was also a major factor in turning them into “just another team” on the visual landscape of baseball. At that time, 17 of the 26 MLB teams had some shade of blue playing a major role in their on-field look — the Padres made it 18. So while the Padres didn’t look like the Giants anymore, they did their best to just blend in instead of standing out.

In 2004, the Padres finally dumped the orange, giving them a completely clean break from their days of the 1980s. The color of sand was in instead. You have to give them credit for at least daring to be unique from 2004-2010, since they decided that they didn’t want to be unique much at all from 2011-2019, when the Padres basically stuck with navy blue and white as their main colors, with some traces of sand sprinkled in (you know how sand sticks). They went with a vibrant shade of gold for 2016, but that only lasted for one season. Boredom reigned and there was nothing special about San Diego’s uniforms at all.

However, there was hope. The brown and gold look returned for Friday home games a few years ago. That hope was enough for the fanbase to latch onto, and the momentum eventually became too strong for the Padres and their management to ignore. The fans wanted the unique look back, and starting in 2020, they’ve got it. The Padres aren’t going to blend in with the rest of baseball anymore. If you’re flipping channels and you stop by their game by chance, you won’t have to pause to figure out which team is which. Nobody looked like the Padres from the 1960s until the 1980s, and now the good old days are back again, and hopefully they’re here to stay.

I’m not really a fan of remakes. There are so many incredible stories out in the world that never get told in the news, a book or on the big screen. I generally can’t figure out why we insist on telling the same stories over and over again rather than trying to highlight new ones.

There are obviously exceptions. The new Battlestar Galactica is orders of magnitude better than the original. There are also those strange 1970s era cartoon versions of The Lord of the Rings which pale in comparison to Peter Jackson’s magnificent trilogy (although, now we’re into film remakes of adaptations of books and that is really a whole other rabbit hole I should save for another day).

All of this is to say that I generally hear about remakes and wince, particularly if it’s one of my favorite movies. So I surprised myself last week by tearing up a bit reading about Amazon’s plans to release a series based on one of my all time favorite movies: A League of Their Own.

Let’s be really clear, this could go terribly wrong in any number of ways. I mean, how many people even remember that they tried this once before? In 1993 the year after Penny Marshall’s movie debuted to awards and acclaim CBS launched their TV version of A League of Their Own. It lasted five episodes.

Despite the history of bad remakes. Despite my own deeply held belief that remakes are always poor copies of brilliant originals. I had tears in my eyes at the idea of “what if?”

There are thousands of stories from the All American Girls Professional Baseball League that have yet to crack mainstream America. In 2018 Britni de la Cretaz wrote about the league’s queer players. In 2016 Emalee Nelson wrote about the Cuban players who played in the AAGPBL – “as long as they fit the light-skinned, feminine image,” which of course begs the question of the talented players who were excluded from the AAGPBL all together. In 2017 Breanna Edwards remembered Mamie “Peanut” Johnson who pitched three seasons in the Negro Leagues after being denied a tryout for the AAGPBL.

There are a world of stories available to a 2019 look at the AAGPBL that were impossible to tell in a mainstream movie in 1992 or on network TV in 1993. If my reaction last week is any indication, I imagine there will be some crying in this baseball series.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now