Perhaps you heard about the popular young singer who isn’t familiar with a mostly-obsolete, almost-entirely-culturally-irrelevant-in-2019 band. Perhaps, this being Thursday and that having been Monday’s news, you’ve already forgotten about it. But I’m writing this on Tuesday, so let’s talk about it.

We know well the beats of this entertainment-industry trope — be it in music, film or sports — a young upstart declares their lack of awareness regarding a former “great”; the old guard expresses their dismay — shaking their fists, yelling at clouds and declaring “that’s what’s wrong with your generation” (ignoring, of course, the fact that their generation had Jim Crow and no seat belts); the people in the middle — the media, the internet commentariat, the colleagues gathering around the proverbial water cooler — report on and discuss and laugh about the flap. And then everyone forgets about it, and then it happens again, to someone else.

When this happens in baseball, many beat writers and fans and broadcasters trot out those myriad tired cliches in lamenting that the player in question is clearly no Student of the Game. (It’s worth noting, by the way, how often being a Student of the Game goes hand in hand with “playing the game the right way,” but, well, y’know.) For some inexplicable reason, honing one’s craft or memorizing the rule book or being a prodigy will never earn a player that distinction quite as quickly as simply being able to name a few of the players those aforementioned writers, fans and broadcasters grew up playing with or rooting for. For the Hawk Harrelsons of the world, to forego a session with the Rapsodo Machine in favor of a few minutes perusing Moose Skowron’s Wikipedia page is to prove oneself a student, or perhaps even a scholar, of the game.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the pearl-clutching party honoring Billie Eilish’s ignorance of the wildly obnoxious song that Rob Zawekci played to win my high school’s talent show for three consecutive years (Screw you, Rob! Maybe my band sucked [we did], but at least we played originals!) No one got mad. No one complained. No one was even surprised. What did happen was that lots and lots of people tweeted about how it doesn’t matter that she doesn’t know Van Halen and why should she know Van Halen anyways and how many (fill in this space with the name of any band that was last a big deal more than a decade before you were born) songs had you heard of when you were 16? And yes, a lot of those people built strawmen in the form of those those monocle-dropping olds who supposedly did get mad about it, but again, it didn’t happen. And it was such a relief.

Anyone who’s taken an Introduction to Psych class — or has even a little bit of experience with what I like to refer to as “being alive” — will understand that all this “back in my day”-ism arises out of fear of one’s own irrelevance, obsolescence and ultimately, death. But I’m hopeful that maybe we’re turning a corner. Not against death, of course — that’s imminent, but at least perhaps against this pathetic and predictable manner of response. Surely the Venn Diagram of baseball fans and Van Halen fans is close enough that if the latter could ignore — or simply be entirely oblivious to–this oversight, perhaps the former will come around too? Perhaps the swag and the bat flips and bright smiles and the marketing campaigns are all slowly working to chip away at the old guard, to take a pick-axe to certain hallowed halls and to unbias the admissions standards for prospective Students of the Game.

Ichiro was in the news again. He played a game against faculty members of a highschool. He pitched and hit, finishing with the Ruthian line of 9 innings, 0 runs, 0 walks, 16 strikeouts and three hits. He threw 131 pitches. His team of friends beat the schoolteachers by a score of 14-0. Everyone has decided this was very fun and proof Ichiro still “has it.”

Ichiro agreed. In his post-game interview with Kyodo News he said: “I can still make it work. No problems at all regarding either my elbow or shoulder.”

I felt an unintentional wave of nausea while reading the sentence. That after he voluntarily threw 131 pitches to dominate schoolteachers for three straight hours he interpreted the question as: how are you feeling, are you OK?

I grew up during Ichiro Mania, practiced his swing in my backyard, defended him relentlessly as rumors of prickliness started to spread. So I’ve tried to digest this fun tidbit easily, but it keeps sticking in my gut. I can’t stop picturing the game like pick-up basketball against an older cousin. After he sinks the first three you know the game has been decided, and you enjoy the feeling of awe, at the proximity to talent beyond yours. But after two hours of being juked and dunked over, sweat dripping into your eyes, you start to wonder if everything is OK with cousin John. Why else would he continue to box you out for rebounds up 65-0? Why, after the game, would John tell your family that he still has it, that he didn’t even tweak his knee.

I feel pity for Ichiro, as I once did for Mike Hargrove, former manager of the Seattle Mariners. Who, famously, quit in the middle of a winning streak. I searched for other managers to quit mid-season. No one manager in the history of baseball left voluntarily after winning a game.

I watched the press conference on July 1, 2007. I was desperate, as everyone was, for a reason for this unexpected departure. One explanation for why he would abandon the two things that seemed to me the most important in the world: winning and baseball. Yet he didn’t have a reason. Not an “I have decided to go to war” reason. Not an “I am sick/my family is sick/I need to finally watch M*A*S*H.” No. Instead he said the words that became so ingrained into my personhood that I once repeated them during a breakup (do not do this). He shrugged his shoulders, leaned down into the microphone, and said, eyes placid, “The lows are too low and the highs aren’t high enough.” He was done. The lows are too low and the highs aren’t high enough? This winning streak wasn’t enough?

In 2005, when Mike Hargrove and Ichiro were on the same team, the two reported to be feuding over their opposing temperaments. Ken Rosenthal wrote at the time:

Mariners Manager Mike Hargrove is in the middle of a fight he can’t win. Either Hargrove repairs his relationship with Ichiro Suzuki or Hargrove soon will be looking for another job.

Now, fourteen years later, I realize they suffered from similar afflictions: the highs were not high enough. Ichiro’s relentless pursuit of elusive perfection, Hargrove’s weary mind in search of joy. Both now “advisers” in some capacity to teams, shuffled off into the periphery of the sport. I no longer think much about either of them, and feel sad only for the realization that in the world of professional sports, retirements are rarely clean, and rarely a mutual decision. Now that a shocking wave of non-tendered players flood a free agent market, more unplanned retirements loom. More players stepping away and preparing statements. I hope, for their sake, the highs were high enough.

Reader, I am VEXED.

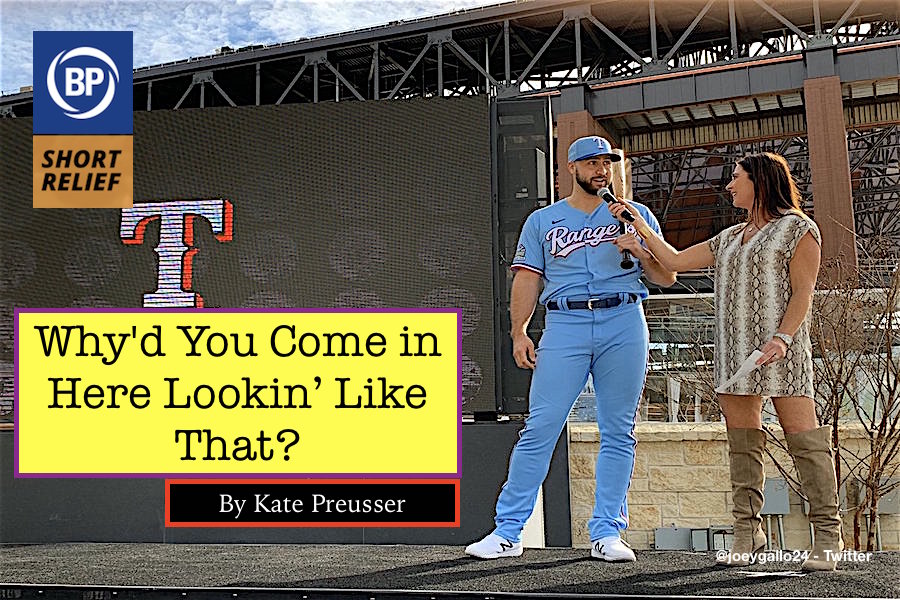

First of all, how dare you. Second of all, no, really, how dare you. I am furious about how good Joey Gallo looks in these threads and several hours after seeing this picture I’m still not over it. Scientists are saying I may in fact, never get over it. This is just my constant state of being now, continually wrung out and bothered-upon by the sight of Joey Gallo looking like a little piece of heaven that broke off and floated down to our dusty mortal sphere. The casual contrapposto stance, giving a subtle hint to the red racing stripe down the leg! Michaelangelo’s David found crumbled into pieces. Forget cutting him out in tiny stars, Joey Gallo has been trimmed from the sky, snipped out like a seven-foot-tall paper doll, and dressed just as impeccably.

There are some tiny complaints: the hat, as my friend and personal style icon Matthew Roberson noted, should be red and white with baby blue accents; head-to-toe baby blue is a little much even on perfect specimen Joey Gallo, and pushes the look just slightly from “serving” to “serving ice cream in a Taylor Swift music video.” Similarly, the Texas-wide design compulsion to “put some ‘Merica on it” rears its head here slightly, with the wholly unnecessary red-white-blue sleeve cap, which for some reason has the navy right up against the baby blue sleeve? Echoing the colors in the font–which is also Very Good — would have been plenty there, but it’s also deeply Texan to screw up one’s design aesthetic in a fit of jingoistic pique, so it tracks. Yet none of this detracts from the fact that I, as a fan of another AL West team, have been pushed to the very brink by the perfection of these uniforms, and forced to admit that Joey Gallo, in addition to hitting baseballs into the very heavens from hence issued these uniforms, is a whole snack. I will be in my chambers the remainder of the afternoon, hold all my calls, unless it is from someone erroneously referring to this color as “powder blue” instead of “baby blue,” in which case, I will see them in court.

Update: A previous version of this article referred to Rangers reporter Emily Jones McCoy as “this team official or reporter or whoever it is.” We have removed the portion of the post referring to McCoy, as it was gratuitous to the piece. No harm was intended to McCoy, but it is understandable why the tone of the comment would offend. We apologize for the error. -Craig Goldstein

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now