While curveballs have been thrown since the late 1800s, the first one pitched into conversation as idiom was, as far as I could gather, in the 1910s. At this point everyone is familiar with the idiom “life threw us a curveball” or “I was thrown a curveball”, which seeks to analogize to life the unexpected change of direction of a ball in mid-flight, leaving the hapless batter flailing at empty air. The Angels were “thrown a curveball,” for example, when Gerrit Cole gave them “the finger” on his way to New York. Like many idioms, however, this one is insufficient.

Last month my mom called me and prefaced some news by saying that life has thrown her “a bit of a curveball.”

Yes, I thought, a curveball. Like when Safeway is out of my favorite flavor of unsweetened seltzer. “Go on,” I said.

“Well, I am going to marry your Uncle Jim.” (My mom insists I clarify that they are not blood relatives, merely both widowed spouses of brother and sister).

Yes, a curveball, I nodded. Like in baseball.

I was immediately made aware of the insufficiency of the idiom in capturing its broad range of applications. A cursory search reveals the range extends from “coping with the death of a relative” to “coping with an unexpected interview query.” So I was “thrown a curveball” when my mother married my uncle, but I was also “thrown a curveball” when my waiter asked if I wanted my soup “cold or hot.”

The goal of language, just as with baseball analytics, is to inch ever closer to the core of truth.

So, what we need, then, is to differentiate the degree to which the news is unexpected or challenging, as “curve” is too broad. There are many curveballs. Pablo Sandoval throws a curveball — neither unexpected nor challenging. What we need is to find the core of the phrase, which, to my mind is: something that appears like something else, and then changes, suddenly catching you at a disadvantage.

To capture Unexpected we are going to use BP’s pitch tunneling data to find the curveballs that most resemble fastballs before changing the most dramatically.

To capture Challenging we are going results-based with the highest Whiff%.

From this simple data we will be able to ascertain which of life’s “curveballs” apply to different situations.

I have separated those categories into three tiers:

Dramatic Life-Altering Event (e.g. accident, divorce, previously unknown identical twin knocking on your door during your shared birthday)

Regular Life-Altering Event (e.g. sudden career change, new couch is actually broken but you didn’t get the extended warranty because you live in the moment)

Breakfast-Altering Event (e.g. actually, that carton of milk is empty)

#1: Dramatic Life-Altering Event

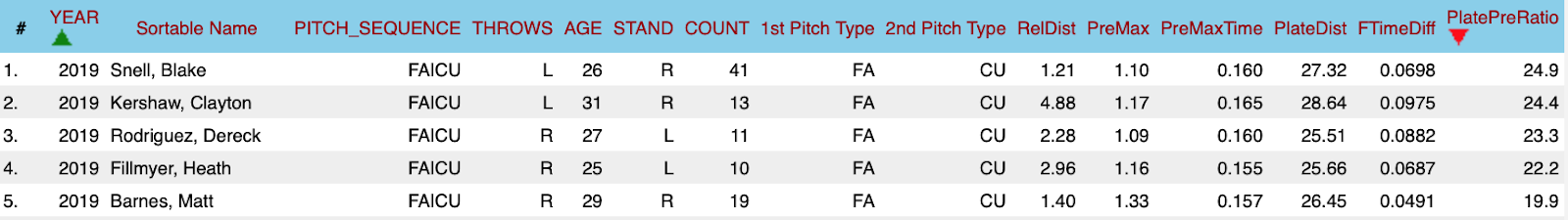

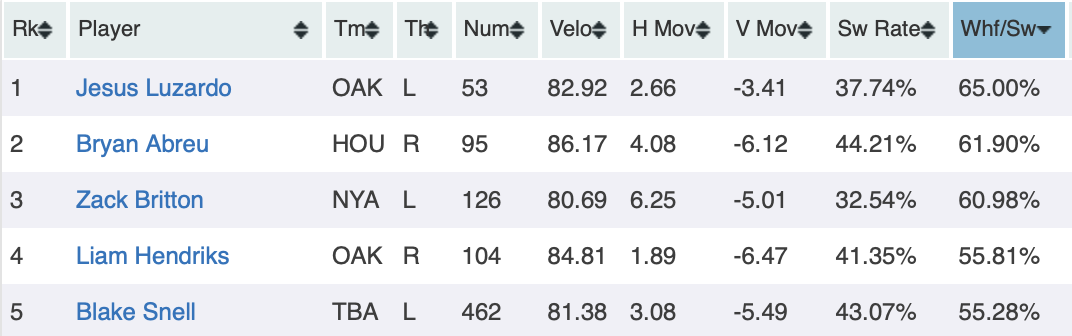

First, we must calculate the most unexpected curveball, using PlatePreRatio. Here is the leaderboard for the pitchers with the most separation between curveball location result relative to how they initially appear (min 10 pairs):

We can see Blake Snell leading the field with a PlatePreRatio of 24.9. This means that while Snell’s curveball was perceived to be 1.1 inches away from the fastball at the batter’s decision point, it landed 27.32 inches away from the fastball at the plate. That is 24.9x different than the batter expected!

Now, the leaderboard for Curveball Whiff% (min 50 pitches):

Luzardo has the edge here, but is so far behind Snell in the Unexpected department, that the Challenging difference (and smaller sample) does not move the needle. Hitters that swung at a Snell curve wound up disoriented, surprised, and disappointed over half the time.

Blake Snell throws the most unexpected, challenging, and life-altering curveball in the major leagues.

#2: Regular Life-Altering Event

To find a regular life-altering event, the “thrown a curveball” that applies to the most average of situations, we must find the most average curveball.

While the top of the range of the Unexpected tier is the actual location of a pitch 24.9 times different than the expected location, in 2019 the average for curveballs was a ratio of 12.8 of difference in inches.

The average whiff rate, or Challenging was an average of a 30.67% whiff rate.

To find the most average, we need seek none other than Trevor Bauer. Bauer has a curveball that has a tunnel of 13.1 inches, just above our average in the PrePlateRatio, ranking 59th out of a sample of 116. While also netting whiffs 32.04% of the time compared to our 30.67% average, which ranks 136th out of a sample of 304 pitchers.

Combined, Bauer is the most average curveball. Best befitting the common usage of the phrase.

#3: Breakfast-Altering Event

Now we have the most egregious use of the idiom, the use that sufficiently drags down the use of the phrase to warrant this exercise in the first place.

OK, so now we have our updated idiom!

For major life-altering events, “Sometimes, life throws you a Snell.”

For regular surprising events, “Really threw me a Bauer, there.”

For non-events, “Yo, this Diet Pepsi was a real Sandoval.”

There. Now to touch base with my Uncle-Dad (Dunkle?) and get a ballpark figure on how long I have to get used to this major Snell he threw me before I have to step up to the plate and go to bat for them both when I deliver a speech about this whole new ballgame.

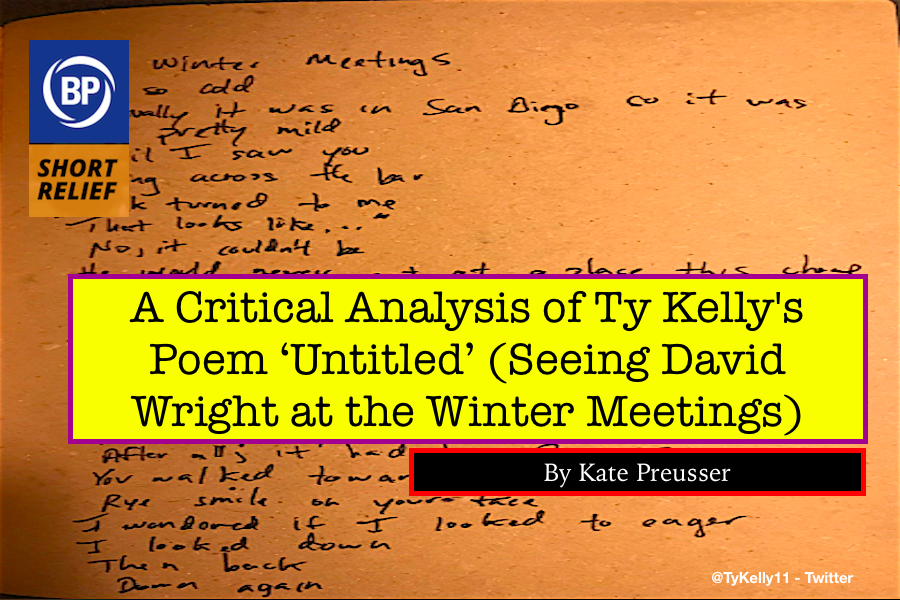

Since retiring from baseball this past August, Ty Kelly has been seeking new professional opportunities. It is the opinion of this author that Kelly should immediately proceed to the nearest institute of higher learning and enroll in an MFA program, as the poem he shared on Twitter yesterday indicates the next great confessional poet also used to wear spikes.

The poem opens with an act of negation: “The Winter Meetings/oh so cold/Actually it was San Diego so it was pretty mild.” The speaker is set up as an unreliable narrator from the jump, instituting a sense of uncertainty in the reader that mirrors the tone of the poem itself. The chance meeting and self-consciousness of the speaker is also mirrored in the poem’s line lengths; “until I saw you” enters as a sharp break, followed by four staccato lines that echo the breathless nature and rapid heartbeat of a chance encounter.

The speaker regains breath and confidence in a more attenuated line: “He would never eat at a place this cheap.” The cheapness of the sports bar is implicitly tied the speaker, already at the sports bar, who struggles for the same sense of esteem willingly granted on the object of the poem.

The harshness of this dichotomy is necessary, however, as it sets up the reveal, and the poem returns to its breathless cadence: “And then you turned around/And I knew.” After the negation and self-doubt of the earlier lines, the poem emerges anew into a stunning sense of surety, the Platonic ideal of “justified true belief.” The subject of the poem is known as a true person, and thus assures the wavering sense of self of the speaker.

Epistemological concerns aside, the poem has not lost its breathless quality; now the speaker is thrown into the quandary of hoping to be noticed. The misspelling of “wry” as “rye” is, according to the poet himself, an “error,” but could also be read as an intentional misstep on the part of the flustered speaker. “Rye,” with the onset capital R, also does double duty as a reference to Rye, New York, a subconscious reminder of the time the two spent together in the Mets organization. Here the objective speaker has let his hand show, in addition to calling the subject of the poem “the captain,” a clear reference to Whitman’s “Oh Captain! My Captain” (the “weather’d ship” of that poem being an obvious nod to the 2016 Mets).

“Rye” is not the only spelling error; there is a missed “to/too” as well. In an earlier tweet, Kelly referred to the “raw” state of this poem, with a wink and a nod, acknowledging the flawed nature of the work but releasing it to the world nonetheless without any cosmetic improvement. Let us all love this way, Kelly seems to entreat: with our flaws on display, authentic, handwritten, and open, and let us not have to wait two years between hugging the people we like best in the world.

Dear reader,

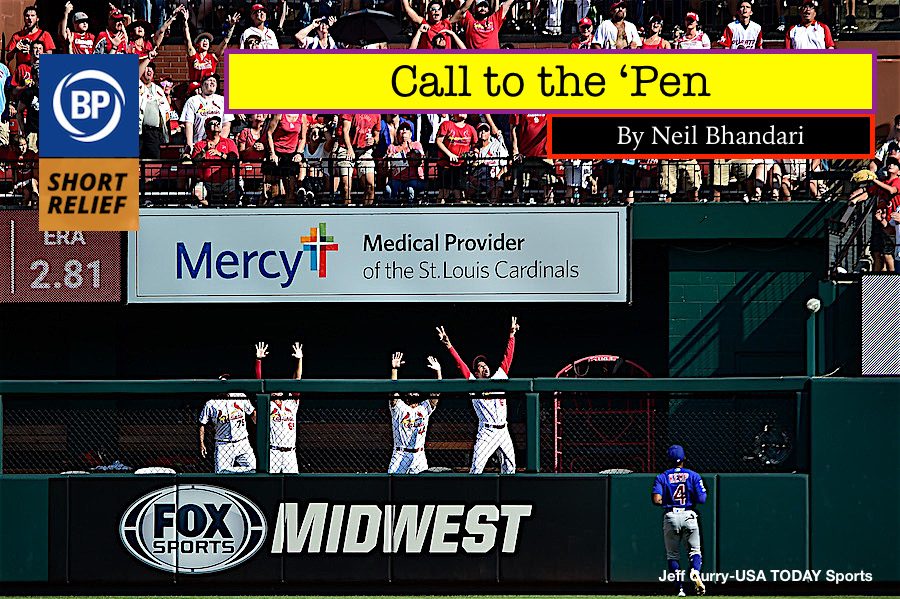

I admit it – I love the new three batter minimum rule that MLB will be putting into effect this season. I work best on my own — I like putting my head down and doing my work, without assistance or interruption. Doing my work. Lots and lots of it. Myself, alone. Accepting the assignment and finishing what I’ve started. I’m a loner, Dottie, a rebel. All of my best ideas come from long, solitary runs or long, solitary showers or long, solitary drinks. Sure, sometimes things can get tricky and maybe it would be easier to call in a pal who’s better equipped to handle the subject or obstacle at hand, but ultimately, there’s a particular satisfaction in completing the task alone, and I’m sure most pitchers would agree. Forcing an individual to complete the work (or inning) themselves leads to creative problem-solving and solution-finding strategies. Now, without further ado, and definitely not because I’m overworked and exhausted and not up to the task of finishing the inning that is hitting my word count this week, let me call to the pen for some opinions on the aforementioned rule, edited for clarity and brevity, from some of the best friends and finest baseball minds I know:

***

DZ (Favorite team – Chicago Cubs): Games move too slowly, but I’m not sure this is the best fix. I’d start by enforcing rules limiting the number of times and length of time a batter can step out of the batters’ box and enforcing the pitch clock. That said, LOOGYs are bullshit and getting rid of players that narrowly focused is fine with me.

***

KH (Favorite team – Chicago White Sox): I think it’s a good idea. It allows for some speciality pitcher situations but that pitcher also has to be versatile. If a manager wants to bring in a LOOGY, that lefty also has to be trusted to go against the next two batters. I think it’s also likely to change some teams batting order strategies.

***

TH (Favorite teams – Seattle Mariners and Chicago Cubs ): A mid 7th inning pitching change on a Tuesday night at 9:19 pm is the dirt worst. I understand you NEED this one guy to face that one guy, but why does it take 6 minutes to bring him in? A slow walk to the mound, cue “Running with the Devil” for a slow jog from the furthest possible location in the stadium, a ball handoff, a little strategy reminder chat, then 12 “warm up” pitches from the guy who’s been warming up for 10 minutes. 4 pitches and a fielder’s choice later…repeat.

***

JM (Favorite team – Chicago White Sox): The rule’s unintended consequences might be kind of interesting as pinch hitting will become more crucial, and strategy could change because you know someone has to finish an inning or face three batters, so you don’t have to bring in your ideal pinch hitter to face them first.

***

CSP (Favorite team – Arizona Diamondbacks): I don’t “like” the rule because I don’t want the game to change in the direction of the general awfulness of our times, in which lumbering, Kafkaesque bureaucracies react always too late and always too feebly to radical disruption. It feels like the league doesn’t actually want teams to play the game. The no-pitch walk didn’t ruin baseball and neither will this, but they do make it less fun–less fun, more policed, more subject to fickle and unimpeachable authority.

***

KK (Favorite team – Chicago White Sox): I think the “the game is too slow” problem isn’t really a problem, but I will say that the only time I get frustrated watching a game is constant pitching changes. The fact that finishing the half inning negates the three batter requirement will really reduce how drastic a change this will be. Also, I’d prefer this not be a rule in the postseason. If you’re complaining that a tight postseason game is taking forever, maybe baseball just isn’t for you.

***

Reader, I’ll be honest with you – I sat down to write this column with every intention of panning this rule. Theoretically, it goes against my every instinct about strategy, game-planning and authority, because any new rule that takes power away from the people on the field seems like an affront. But the more I thought about it, the more I became convinced. I like that it will put pitchers and managers in uncomfortable situations and that it will force them to come up with creative solutions. Unfortunately for them, one of those solutions will no longer be to call on their friends when they’re clearly running out of gas.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now