Jackie Bradley is tough and smart. In a perfect world, of course, he wouldn’t so frequently slump worse than almost any other hitter in baseball, but those slumps seem to be an inextricable part of Bradley’s identity as a hitter and he’s recovered from multiple slumps that might have ended the career of a lesser player.

This May 1, he woke up batting .148/.224/.182, with 30 strikeouts and three extra-base hits (all doubles) in 99 plate appearances. Since then, however, Bradley is hitting .250/.356/.500, with 40 strikeouts and 18 extra-base hits (seven of them homers) in 150 plate appearances. It seems like another slump is always a lurking danger for Bradley, but for a guy who’s been an elite defensive center fielder throughout his career, waiting out those slumps is far more than worth it.

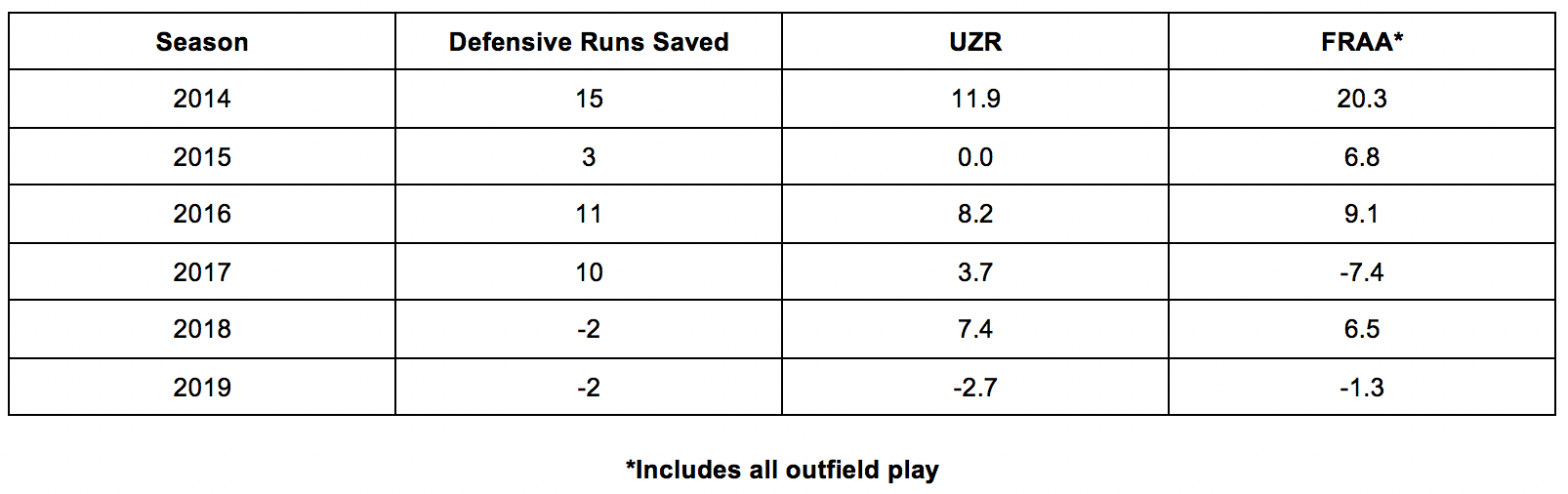

Alas: Bradley is perhaps not an elite defensive center fielder anymore. By every major public defensive metric, he’s undergone a defensive decline that now has him in the red as a fielder. Some metrics describe that descent as more sudden and sharp than others, but the story is roughly the same in each telling.

That defensive backslide has coincided with Bradley, 29, losing a half-step in terms of sheer speed. His average sprint speed, according to Statcast, hovered between 27.4 and 27.8 feet per second from 2014 through 2018, but is down to 27.2 feet per second in 2019. His average time from home plate to first base on full-effort runs has crept up from just under 4.3 seconds in both 2017 and 2018 to 4.43 seconds this year. That incremental loss in speed is unlikely to reverse itself, and puts pressure on Bradley to keep evolving and improving in the subtle things that make up the art of fielding.

One way Bradley might be doing this is by playing deeper. He’s done this before, from 2016 to 2017, but this is a more thoughtful adjustment. Last season, Bradley’s average starting depth when playing center field was 317 feet. This season, that number is 324 feet. That lets Bradley get back and make some of the toughest, highest-value plays that might otherwise elude him — notably, home-run robberies like his game-saver in Baltimore last month, and wall-bangers like the graceful one on which he stole a triple from Twins shortstop Jorge Polanco on Tuesday night.

Still, his numbers are racing in the wrong direction. One might plausibly argue that playing deeper is a mistake for Bradley, given that broader narrative. To tell whether it really is, however, and to break down the pros and cons of various positioning choices further, consider the center fielders for the Twins, whom the Red Sox visited for some 35 innings of scintillating baseball this week.

Byron Buxton went on the injured list Tuesday, nursing a bruised wrist suffered when he was hit by a pitch earlier this month. That made room on the roster for Jake Cave, who’s in his second season riding the shuttle between Minneapolis and Triple-A Rochester, and who saw his first action in center field this season when he started Tuesday. Buxton, somewhat infamously, plays a pretty shallow center field. Cave, by contrast, played deeper last year than any other player who saw meaningful time in center field.

Max Kepler, who fills center field when Buxton is unavailable and Cave isn’t around, plays exceptionally deep, too. Generally speaking, that’s the strategy teams are embracing lately — the guiding principle that seems to lead to the best defensive outcomes. In the Twins’ clubhouse, I asked Cave whether his and Kepler’s positioning are part of an organizational philosophy grown out of that awareness.

“That’s me,” Cave said. “That’s something I’m more comfortable doing. I know Buxton, for instance, likes to play shallower, but [that’s] because he’s the fastest guy in baseball.”

Interestingly, though outfielders receive ample guidance in adjusting their positioning from batter to batter — Cave was 334 feet from home plate on the first pitch to Mookie Betts on Tuesday, but just 329 feet away when Andrew Benintendi stood in just afterward, and moved far toward right-center field when J.D. Martinez took his turn — Cave said teams largely allow fielders to set their own anchor point, playing as deep or as shallow as they feel comfortable playing.

“I’ve found [playing deeper] is comfortable for me, so I decided that I wanted to do it, and I’ve had some success with it. Good coaches aren’t going to change something if you’re doing things right.”

Indeed, playing deep works reasonably well for Cave, who’s stretched athletically when he plays center field. Last season, in 565 innings there, Sports Info Solutions credited him with a +2 (meaning he made two plays more than an average fielder would have made) on deep balls, and with a +3 on medium-depth balls. Virtually all of those added outs were wiped out by his -4 on shallow balls, but as Cave acknowledges, that’s by design.

“For me to play back a little bit, I can get a good jump on those balls coming in, and even if I don’t get those, hold them to a single. I’d rather do that than getting beat over my head for doubles, because that’s when people score.”

Bradley, however, isn’t enjoying the same benefits from playing deeper that Cave is. Here are his numbers on Shallow, Medium, and Deep balls in 2018 and in 2019, according to SIS.

On deep balls, specifically, Bradley is certainly performing better. It appears, though, as if that marginal improvement has come at the cost of too many balls to either side of him, and in front of him. He’s not catching more balls this way; he’s just catching different ones.

The reason for that might relate to Bradley’s mentality and approach to getting a good jump as the ball leaves the bat. He rates exceptionally well in Statcast’s new outfielder “jump” metrics, but primarily by getting going sooner and getting up to speed quickly. Speaking to Chad Jennings of The Athletic last year about several of his greatest catches, Bradley explained his thought process.

You’ve got to be able to get back there in time. And that’s why I say the last few feet are the most important because that’s when you have to make your small little adjustments. If you’re thinking about making those adjustments earlier on in the route, then you might not even have the opportunity to catch it because you won’t get back there in time. You’ve got to get there first. Make the adjustments when you need to it.

That’s not a bad way to approach the craft, per se. There might be no such thing as a bad way to approach the craft, really, if a defender is committed, intentional, and open to feedback. However, Bradley’s mentality might be better suited to the shallower depth at which he used to play. After all, playing a little deeper can mean seeing the ball a hair later, or a hair less well, when it first leaves the bat.

“Maybe,” Cave acknowledged, when I asked whether he trades anything in terms of immediacy for the extra time playing deeper gives, “but that’s why I like it. You give yourself that extra half-second or whatever. You might not see it as well at first, but you’re probably not gonna get beat [by a false start]. And if I’m gonna get beat, I’m gonna get beat in front of me.”

There’s a stark difference between the two players’ concept of the moment when bat meets ball. Bradley is thinking about getting up to speed, about having his momentum going so that he can beat the ball to a spot and make the necessary adjustments at the end. Cave is trying to optimize his angles, his odds, and his ability to anticipate. By playing extremely deep, he eliminates some of the guessing. If he’s going to have to go a long way, it will be in. He can spare the millisecond to ascertain whether that’s the case, or whether he has a more leisurely trip back to get the ball. (For what it’s worth, Cave rates just fine in Statcast’s jump metrics, too, though not on Bradley’s level.)

Buxton, very clearly, operates the way Bradley does. By playing shallow, he trades some of the time Bradley gives himself to make last-second adjustments (like, say, bracing for impact with an outfield wall) for the ability to take away bloop singles, but his sheer speed renders all of that relatively unimportant. Still, it’s notable that his approach mirrors Bradley’s. So do those of Ender Inciarte, Billy Hamilton, and Leonys Martin — guys who famously play shallow in center.

Those players all get moving early, with less regard for precise routes than others. Meanwhile, guys who play deeper (like Mike Trout, Kepler, and Mallex Smith) take cleaner routes but sacrifice first-step quickness. It might be that, if Bradley wants to transition into playing deeper as a way of taking more extra-base hits from opponents despite his declining speed, he needs to think more like Cave and the other guys who also position themselves further from the plate.

That approach might cost him some of the dazzling plays that make him so much fun to watch, but it would yield better outcomes than pairing a shallow center fielder’s philosophy with a deep one’s geography. It’s also likely to keep him healthier, as he ages. Bradley already plays the wall better than Buxton, whose death-defying bull rushes at the barriers shorten the lives of nervous Twins fans a few times each season, but playing deeper means not having to go as fast or decide as quickly how to handle it when near the fence.

There’s one other consideration, though, and one that Bradley might do well to weigh more heavily: his throwing arm. Like Buxton (but distinctly unlike Cave), Bradley has an elite arm. A great outfield arm plays better if its owner plays shallower. Ground-ball hits to a shallower outfielder make it harder for a runner to take an extra base. Making the catch on a deep drive with runners in scoring position and fewer than two out is preferable to allowing a double, but a run is still likely to score.

With apologies to Ramón Laureano, most impactful outfield throws come from somewhere inside the imaginary circle 300 feet from home plate, so a fielder playing closer to that line might get more value out of his arm than one who starts deeper. Between the strength of his arm and the way he approaches his reads, Bradley might be doing himself (and the Red Sox) a disservice by playing as deep as he is. Then again, if he can adjust the latter, he might be able to recover what he’s lost afield. Given his high baseball IQ, it’s still a decent bet that he gets back to some higher level of overall defensive performance.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now