Major League Baseball has a lot of awards. There are players of the week, players of the month, All-Stars, MVPs, and batting titles. The Baseball Writers’ Association of America votes on a few of the above, and also on who gets inducted into the Hall of Fame each year. Not to be outdone, or excluded, the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America does a shadow ballot for many of the same awards.

There is one award that stands alone. The Roberto Clemente Award is “the annual recognition of a Major League player who best represents the game of baseball through extraordinary character, community involvement, philanthropy and positive contributions, both on and off the field.” Every team nominates one player, and I always love reading the incredible work my baseball heroes are doing in their neighborhoods and communities. It’s a fitting tribute to the legendary Pirates outfielder who died too soon trying to deliver hurricane relief supplies to Nicaragua on New Year’s Eve 1972.

But every year, as Roberto Clemente Day is celebrated and this great man is remembered for his humanitarian work, I’m drawn to one of my favorite pieces of baseball writing about Clemente: The Greatest Forgotten Home Run of All Time. You see, on July 25, 1956, Roberto Clemente was in his second season in the majors when he hit the only inside-the-park walk-off grand slam in the history of baseball. Far from celebrating the feat, Clemente’s manager remarked at the time that he was lucky to not be fined for running through a stop sign at third base.

Baseball is a game that still bristles at the type of flash and brilliance Clemente embodied. The instincts and confidence that led a 21-year old Clemente to blow through Bobby Bragan’s stop sign is on display every night by exciting young players across Major League Baseball. Despite a catchy “Let the Kids Play” ad campaign, across the league players still take heat for bat flips, celebrations, tilting their caps, or otherwise daring to play baseball with their hearts on their sleeves and their hair on fire. The phrase “playing the right way” never fails to rear its ugly head, and it seems to be deployed more often at young players of color in moments all fans should celebrate.

Clemente is rightfully in the Hall of Fame, and if you know what to search for it is possible to find an article here or there about one of the greatest home runs of all time. But as we celebrate Clemente’s humanitarianism, we should also celebrate his baseball brilliance and be wary of the reactions that would seek to diminish that. This postseason, one of the greatest gifts fans could give Clemente’s legacy is committing to be watchful for the same old racism that put baseball’s only inside-the-park walk-off grand slam in the category of an offense that barely escaped a fine.

For six years, you stood outside the shop windows on Flatbush Avenue to see them play. Under the covers, you read and reread last week’s tattered copies of The Sporting News, the ones that the barber gave you after the new ones were delivered. Later you had your little transistor radio under your pillow. You listened to WMGM after that heavy hand hit you, after she spilled that pot of boiling water on your legs. You listened after the beating from the paddle, when you handed in your unfinished homework. The teenagers at the pizzeria talked about the Dodgers all winter long. You swept the floors and hung on every word.

They finally won it all, and then you hardly minded the angry kitchen when you went home. You’d been forced to surrender nearly everything you’d earned to pay for the alcohol that made her mad, but you’d hidden away enough. You spent it proudly on a pennant. You were elated by your Dodgers, the club that never stopped trying to win. You gave them your heart and everything in it. They were the team that wiped away your pain; Amorós’s improbable catch, Hodges and his two RBI, Podres’ complete game. For the first time in your life, you knew who you were. You wore their cap. You were their fan.

That’s when they left. At first you couldn’t believe it, but the agony of the borough helped you understand. You meant nothing to them. You were invisible. It was your soul that they ripped through on their way out of town. You thought that they were home and family, but that was wrong. You were just a visitor to them, so when they left, they left you behind. At home, brokenhearted, the hands on you were heavier, the welts more painful, the radio, silent. You put the cap inside the pennant. You rolled it up and stored it carefully, in a bag.

Next time the yelling started, you yelled back. The heavy hand was heavier, but you hit back. Then you left. In the Bronx, from beneath a dumpster behind your building, you heard a kitten cry. You rescued the tiny thing; at home, you bottle fed him and gave him a bath, before he climbed inside your shirt and went to sleep. You waited around that dumpster for a month, hoping his mama would show up, but she didn’t. So you bought him toys and food. Now you sleep together at night, safe and uninterrupted. You named him Yogi.

For a long time, the Yankees were a light in the darkness that was my childhood. I’ve written about that for Fangraphs and on Twitter, about how my father would come into my room late at night after my mother was sleeping and regale me with tales of the most recent Yankees game. When my mother forbade me from watching baseball, thinking it contributed to my transness, my father would invite me on car rides with him to work or the grocery store, leaning over and whispering the score of the latest Yankees game into my ear. The Yankees were, in a very real sense, my lifeline.

I graduated college in 2009 and started law school, and finally — finally — had enough money to leave home and get my own apartment. That year was the Yankees’ magical run to a championship, behind Mark Teixeira, A.J. Burnett, and an in-his-prime C.C. Sabathia. That was the year Alex Rodriguez actually came through in the postseason, Hideki Matsui hit like he hadn’t in years, and Robinson Canó became a truly elite player. The Yankees’ playoff journey, to my mind, was a reassurance I was going to be okay. The Yankees were there for me when I needed some degree of normality, some underlying force of my own courage. I could do this. Years before I socially transitioned, I watched the World Series as myself. The Yankees were the familiar, telling me everything was going to be okay.

Then Aroldis Chapman happened, not once, by twice. The Yankees traded for a man who had abused his partner, then traded him away and signed him again. They used his actions — the evil he had done — as leverage to bring his price down.

They betrayed me.

It was then I realized I couldn’t be a Yankees fan anymore. I couldn’t root for the team, because rooting for the team meant rooting for the man on the mound at the end of it: the tall left-hander with the blazing fastball and the belief problems in relationships should be solved with fists and guns. That was too close to my childhood. I might as well root for my mother. So I swore off the Yankees. I rooted for the Nationals for a while, and the Padres, and the Padres embraced Miss Molly as one of their own.

And yet.

I wanted, desperately, to love the Nationals or Padres as I had the Yankees. But the new and unfamiliar isn’t comfortable. And when the Yankees let Domingo Germán pitch after learning he, too, had used physical force against his partner, I knew I had made the right decision.

And yet.

There’s still the old familiarity, that unseen force that draws me, like a moth to a flame. I still smile, unbidden, at Gary Sánchez’s little swagger at the plate. I still seek out Didi Gregorius on Twitter. I still marvel at Brett Gardner reinventing himself for the umpteenth time in his career. I still, unconsciously, call out the umpire for a borderline call that doesn’t go the Yankees’ way.

I don’t want to do any of those things. I can’t help it.

I want the Yankees to lose. I want them to lose for hurting me. For validating pain and anger and fear over love and belonging.

And yet.

I want the Yankees to win because, for so long, they were the only love I knew.

Baseball is a mirror. We watch players struggle and slump and scuffle and fail and every once in a while do something incredible, and in those struggles and successes, we see ourselves. As a kid, every favorite player I ever claimed had some mostly-superficial attribute – left handed, not very tall, primarily a singles and doubles hitter – with which I could identify. With time and age, my favoritism has moved from those sorts of things to a more general likability and relatability. And so, despite having always been steadfastly jersey-averse, this April I bought my first ever — a Yu Darvish Nippon Ham Fighters pullover — after realizing “wow this guy is so undeniably talented and yet his intellect and emotionality actually seem to be something of a hindrance to his sustained success — I recognize that! I know that! I love that!” At this point, what these players actually do on the field for three to five hours every night has next-to-nothing to do with how much I root for or against them as individuals.

Which brings me to Sean Doolittle. Everybody loves Sean Doolittle. Everybody. And by everybody, I mostly mean the small, extremely bookish, extremely communist section of baseball twitter that I like to skulk around in. In that cute little corner of the internet, Sean has already won this year’s Rookie of the Year, Comeback Player of the Year, Most Valuable Player and both the AL and NL Reliever of the Year Awards. One guess at the frontrunner for Cy Young. Gimme an S…Gimme an E…Gimme an ok, ok you get it.

At a moment when the President is *gestures at every terrible thing everywhere* and ownership groups willfully admit that they are primarily in the business for the purpose of profit-generation and we know more than enough about the thoughts and actions of so many of the players to ever convince ourselves that they share our socio-political views, it can be hard sometimes to figure out and justify what exactly we’re rooting for here. Sean Doolittle is just one relief pitcher on one team, but in his and his wife Eireann’s work with Syrian refugees and on behalf of the LGBTQIA community, in his support of local independent bookstores, his thoroughly articulated reasoning for skipping the Nats trip to the White House and the myriad other issues he lends his efforts towards, we see one of our own. We recognize someone whose values extend beyond the luxury that a life in professional sports has afforded them. We’re reminded of how good it feels to wholeheartedly root for a player. We’re allowed, however briefly, to believe that it’s ok to not be cynical and to not be required to compartmentalize our morals to enjoy the game we love.

So congrats, Sean, on your forthcoming 2019 Manager of the Year Award — you deserve it, buddy.

Once again I have been asked, by myself, to improve on an American classic.

Ernest Thayer’s 1888 enduring poem about a star baseball player who fell victim to the farce of the one-plate appearance sample size didn’t have to be this way. You probably remember the disappointment strikeout, but possibly not remember the game situation.

It was 4-2 the other team, with Mudville up to bat in the ninth. With two outs, Casey was due third. Ahead of him were two suboptimal batters, Flynn and Jimmy Blake. Flynn singled and Blake doubled. There are other questions about how Flynn didn’t score from first with two outs on a double, but if he’s a bad hitter then it stands to reason Flynn wasn’t a good runner either. Because it’s the 1800s, and speed is everything. Well, that and laudanum.

So Casey represented the winning run, but! There was an open base. They absolutely could have intentionally walked him, and I’ll go a step further and say they should have. We were not told who batted behind Casey, and this is why Thayer didn’t write a lot of great poems. Too shortsighted of a visionary, if you ask me. But it seemed like the obvious play: Casey was the star, and you don’t let your star beat you.

Yes, I know he struck out. That’s not the point! The point is, this could have definitely backfired on the other team and instead of being a poem about how you sometimes don’t win, this could’ve been poetry about the guy who batted behind Casey. Let’s call him Fluffo. This could have been a poem about Fluffo, mired in a slump, who finally got a chance to drive in some runs because Casey, who always got the chance, didn’t get the chance. Baseball has its stars but it’s always been about the assembly line of teammates and making the most of your chances when the opportunity finds you. Teams can’t win championships with just a few stars. Just ask the Tigers.

If this is how the poem went, we might have nipped the intentional walk craze in the bud over 100 years ago, with crusty managers grumbling to the media about why they didn’t intentionally walk the cleanup hitter for fear of getting Fluffed. And honestly, who does.

Adults are busy. “I’m busy,” they say. Or, “Maybe I will, once things aren’t so busy.” Or, “I would but your poetry reading across town with hard seats and no air conditioning doesn’t appeal to me.”

With our busy lives and more hours of baseball in a day than hours of day in a day, we don’t have time to watch bad, boring baseball. We must prioritize our viewing for max interest, so I have compiled a list of the most unwatchable hitters.

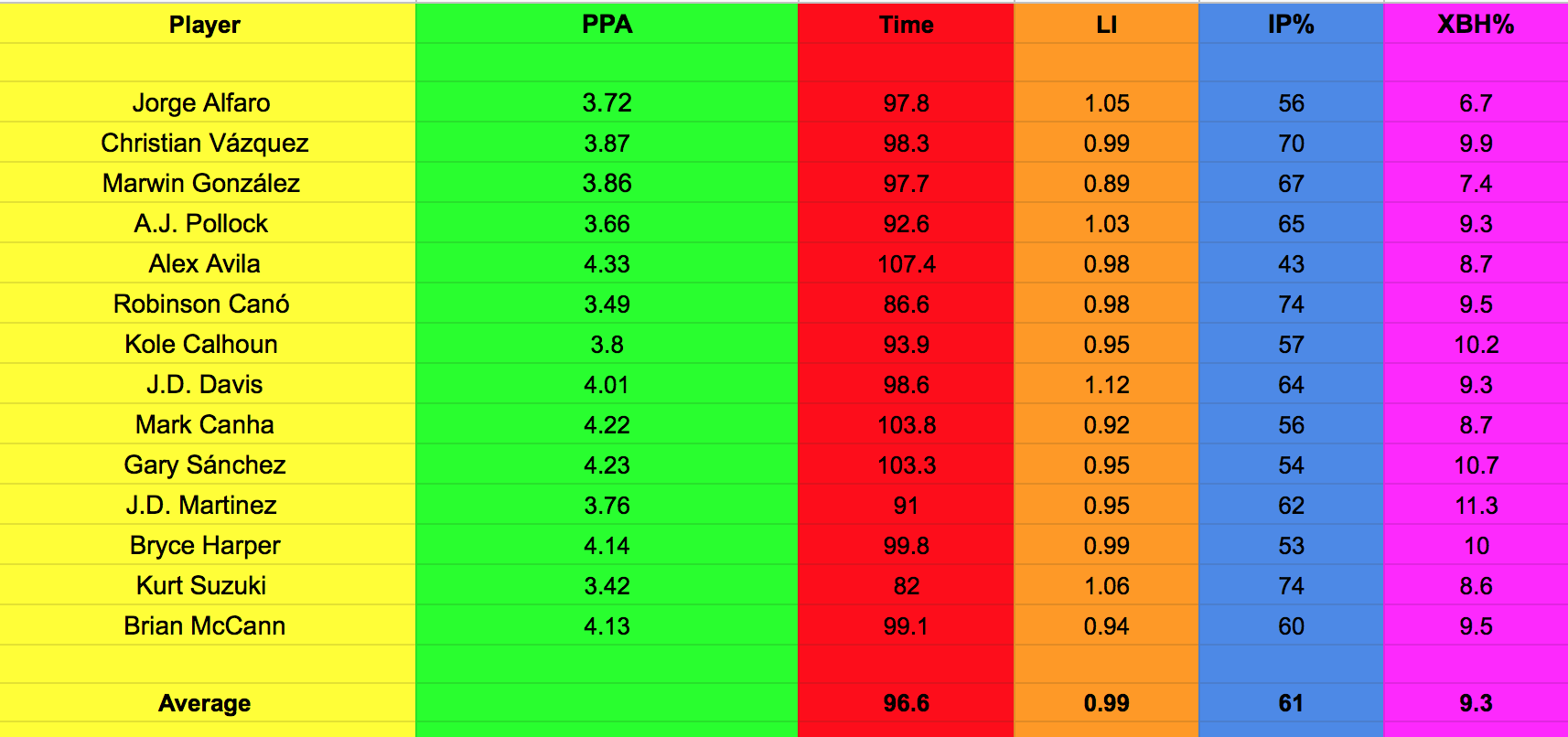

To do this, I described what I consider a boring at bat and assigned a measurement: slow (batter pace), long (pitches per plate appearance), inconsequential (leverage index), anticlimactic (balls in play and extra base hits), and Plays for the Angels (Angels Player). I can think of nothing worse than a slow, ten pitch at bat that ends in a walk or strikeout in the ninth inning of a decided ballgame by Kole Calhoun.

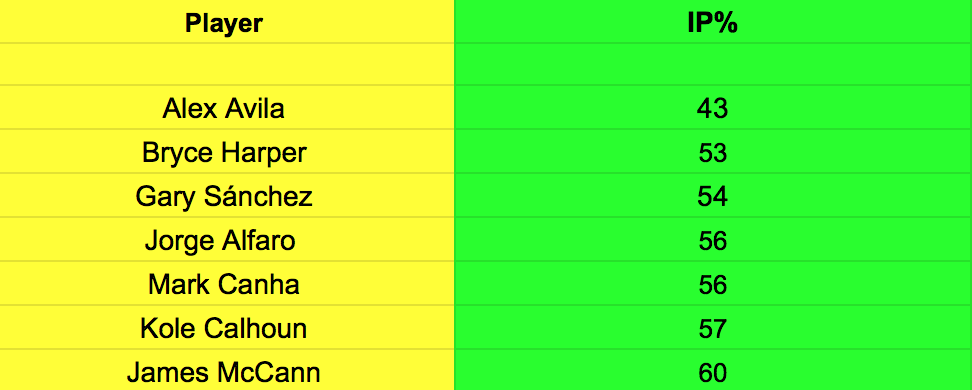

We’ll start with pace to get our Leaders of Snooze because time between pitches is the least interesting aspect of an at bat. Nothing can happen in this time save for the adjustment and readjustment of various pieces of equipment (if you know what I mean).

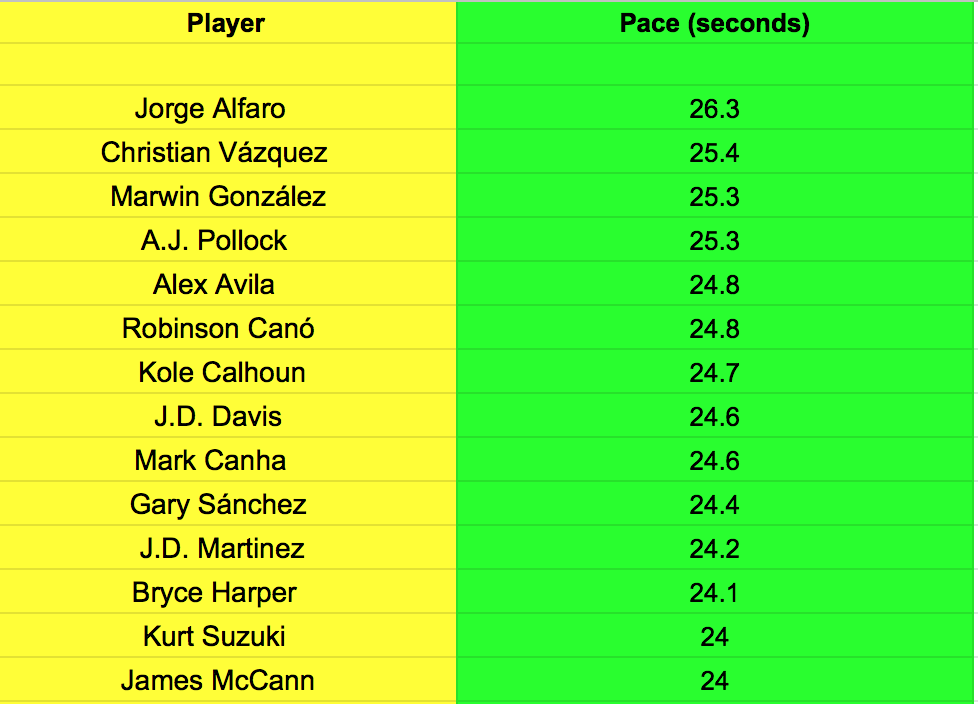

The average pace for a hitter this year is ~21 seconds between pitches (wow). A quick pace is about 19 seconds, while a slow pace is 23 seconds. There are 14 active players with a pace over 24 seconds. That will be our group. Look upon these wastes of your precious time.

While taking time between pitches is annoying, the total length of an at-bat is where we feel the day slip by. By multiplying pace by pitches per plate appearance we get the average duration of their average at bats. In MLB, the average hitter’s at-bat lasts one minute and 23 seconds (83 seconds). Not so with our intrepid group of layabouts.

The average of our narcoleptic group is one minute and 37 seconds (97 seconds). There are nine hitters who take longer than the group average. The three worst culprits are Gary Sánchez (103), Mark Cahna (104) and Alex Avila (107). 24 seconds may not seem like much, but think about clicking on a website and waiting an extra 24 seconds for it to load. I’ve stormed away from my desk for less.

Yet, waiting can lead to tension. A long at-bat in the ninth inning of a tie game builds suspense. Surely we don’t want to punish the best of baseballs’ moments.

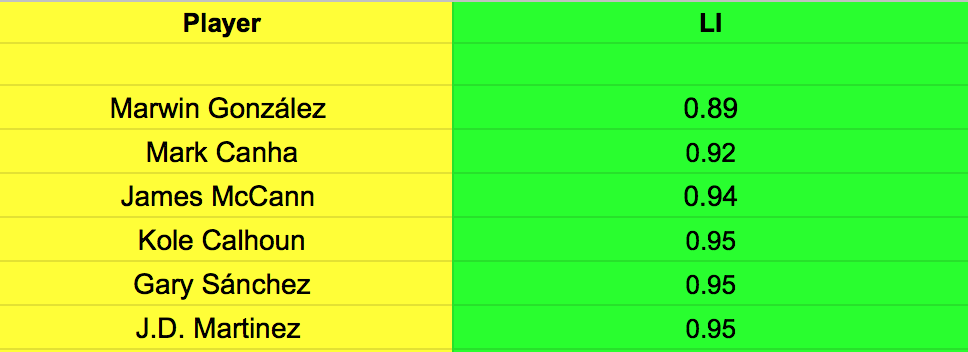

So we sort by leverage index (1 is average) to see who is taking their time in tense situations and who is stealing small bits of my life. I’m running out of room so I’ll just list the ones significantly below league average.

The rest of the list is somewhere around the average, with only Alfaro (1.05), Pollock (1.03), Suzuki (1.06), and Davis (1.12) getting tense at bats.

A long, non-tense at bat should at least allow for some interest by getting more players involved in the game. 63% of PAs end with a BiP, and our list of 14 dolts averaged a little less at 61%. Here are the worst of them (below the Boring Group average).

Last, we should examine how many at-bats end with an extra base hit. After a ten pitch showdown, a double off the wall feels worth it no matter the leverage. While the average is 8.6% across the league, ours is quite a bit higher at 9.3%. Only Jorge Alfaro (6.7%) and Marwin González (7.4%) are below league average, while J.D. Martinez (11.3%), Gary Sánchez (10.7%), and Kole Calhoun (10.2%) are in the double digits.

In total we have this, sorted by pace.

Not a good looking bunch. I weighted each category equally, because that’s what I could do, and taken together the hitter who best represents Long and Pointless on the axis of watchability is… wait for it… keep waiting for an extra 24 seconds… Alex Avila!

Here’s a typical Alex Avila at bat: Down by three in the fourth. He takes a pitch. Steps out. Stares off into the middle distance. Wonders how bread got so popular. What is it about bread. Steps in. Another pitch. Another step out. Another stare off. Taps his toes. Should I buy stocks. Is baseball a stock. Another pitch. Looks at dugout. Thinks about all his friends over there. Another pitch. Strike three. There’s two minutes of your life.

Here’s an actual video of Avila from 2017 (of a high-leverage situation):

Interminable.

Some slow paced hitters (J.D. Martinez!) turned out to be watchable. Five were below average in watchability in at least 4 of the 5 categories. Here is the list in order of unwatchability:

1. Alex Avila, human unskippable ad

2. Mark Cahna, human loading screen

3. Gary Sánchez, human airport security line

4. Bryce Harper, human conversation with your great uncle

5. Jorge Alfaro, human person

Maybe one day we’ll have enough time to find the worst pitcher. But I’m pretty busy next week.

The buzzsaw snarled and rattled in the yard.

That’s how Robert Frost’s “Out, Out—” begins: The buzzsaw snarled and rattled. It is almost certainly the greatest poem ever written about a kid cutting his hand off with a circular saw.

Sadly, those outs in the title have nothing to do with baseball, and refer instead to the famous passage from Macbeth:

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

All our yesterdays were luminous with doomed plans. We were finally going to learn French. We were finally going to win the World Series. We were going to murder the king and take the throne with absolutely zero consequences. We were going to instruct the DJ in firm, clear language that under no circumstances would the “Electric Slide” be played at our wedding reception.

Robert Frost is big on maybes. He likes to do this thing where he tells you how something went down, and then he goes back and says on second thought, maybe it went down like this. The kid with the hand — sorry, the kid without the hand — is no exception. The saw,

Leaped out at the boy’s hand, or seemed to leap—

He must have given the hand. However it was,

Neither refused the meeting.

It’s a good thing to remember; that the truth is often muddy, and cause and effect can be hard to determine. Maybe the better team won; maybe the other team just blew it. Or maybe it’s just that somebody had to win and somebody had to lose. Nobody was planning on losing (except the Marlins).

Plans fizzle out in all sorts of ways. Maybe we get busy and forget. Maybe we scratch and claw but lose in the end. But sometimes we don’t even stand a chance. Sometimes the universe decides that we’re going down without a fight, and those plans are snuffed out before we even know what happened. There’s a phrase for that, and it’s a good one. It’s called running into a buzzsaw.

Stephen Strasburg is familiar with both the expression and the feeling. “It’s kind of tough to say what’s going to happen in the playoffs,” he said recently. “You have a great year, and you can run into a buzzsaw. Maybe this year we’re the buzzsaw.”

Maybe.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now