Of the many games we’re playing on Twitter this week to distract ourselves from the outside world, a popular ask is for everyone’s top athletes, or albums, or other piece of pop culture. When the question of the top all-time episode of television came up, I saw plenty of good nominations. But one will always stick with me, and I thought of it immediately.

Even if you’ve never watched “Mad Men,” I’d imagine that scene still evokes something inside you. If you have, you know all the deeper plot lines running through Don’s presentation. It’s an absolute killer.

In the monologue, Draper says that nostalgia means “the pain from an old wound.” While that’s achingly poetic for that iconic scene, it’s not quite right. The word is a combination of two Greek words: “nóstos,” meaning “return home,” and “álgos,” meaning pain. It’s actually that pain—that sickness inside of us as we yearn to return home, to a place we know, where we’re comfortable, where there will be baseball tomorrow, and every day after that, until the earth tilts away from the sun enough to wither and shake the leaves from the trees again.

We miss baseball in the winter. We wait for it. But we don’t mourn its absence in the way we’re doing now.

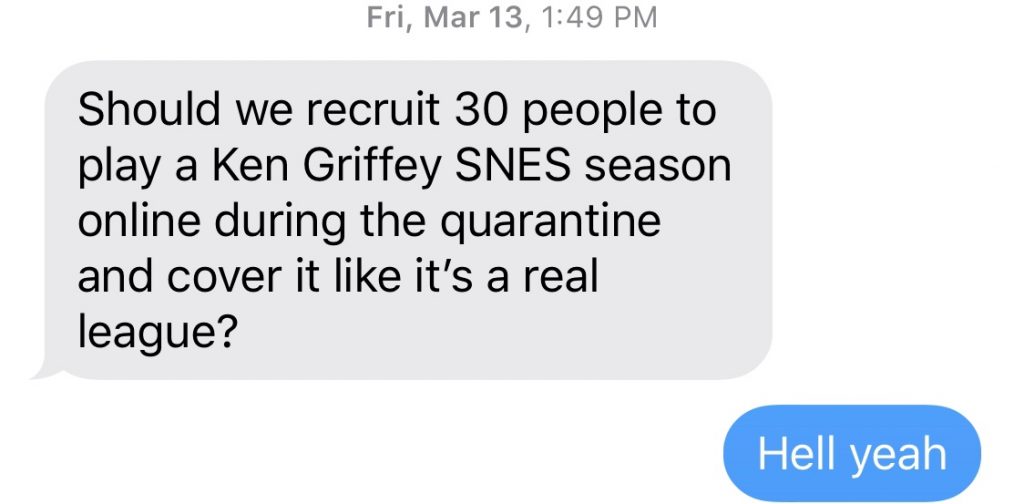

That’s why, on Friday, March 13, the day after MLB formally announced what had become an obvious necessity and postponed Opening Day, my friend Rory Murphy sent me the following text.

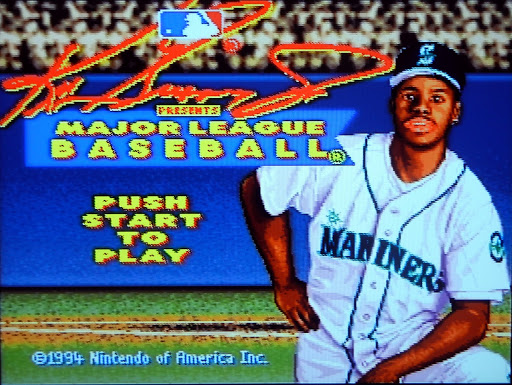

We spent the weekend troubleshooting logistics, creating a league from scratch with no particular template, but that we knew needed to get up and running as quickly as possible. Using a PC mod of the Super Nintendo classic Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball, a handful of Google Sheets and Docs, a dedicated Slack channel, and a Twitch stream to broadcast our weekly Sunday Evening Baseball game, exactly one week later we held the Social Distancing Baseball League Draft.

In all, 28 players—friends, colleagues, fellow sportswriters, even internet strangers—signed up to donate at least $30 each for their entry fees, with all the proceeds benefiting Capital Area Food Bank. Last Friday, we officially made a $1,000 donation.

Why would so many people willingly jump into our crazy idea? Honestly, I was surprised at my own unbridled enthusiasm. As a former minor league PR director, I’d like to think I know a good promotion when I see one, though my job back then was often as the voice of reason and moderation for our exceptional creative team in Fresno, poking the necessary holes in ideas to see if they’d still float. This has all the pieces of a great minor league promo: Competitive fun, fundraising for a great cause, and that nostalgia.

“Technology is a glittering lure. But there is the rare occasion the public can be engaged on a level beyond flash, if they have a sentimental bond with the product.”

I’ve long believed that good coworkers and bosses do their best to find a way to say yes to as many good ideas as possible, while the bad ones keep finding ways to say no. It can be so easy in these moments of isolation to say no to things, to let yourself get walled off from the world. We’ve done everything we can to say yes to every good idea that’s been proposed. That so many other people said yes in turn to participating in this weird little community speaks, I think, to the chord it struck.

Because it’s not a video game. It’s baseball.

There are three strikes, and three outs, and nine innings. There are pinch-hitters and doubles in the gap. And the fact that there are only 28 teams because the game platform was built pre-D’backs and Rays, sorted into old school divisions—the Braves still in the NL West, the Astros in the NL and the Brewers in the AL—but with modern rosters, it all feels right for this profoundly surreal moment. It’s past and present, simultaneously, a simulacrum of the game we grew up with, colored in with all we’ve learned and experienced and lost ever since.

I find myself, in the quiet moments, loading up another game, just against the computer, finding comfort in the familiarity.

Playing is also a skill to be learned, or relearned for those who grew up with the game. The defensive learning curve is a sharp one that takes a handful of games to get a basic grasp of and many more than that to master. Adjusting to the timing of pitches, learning how the rhythms differ from actual baseball—it’s the kind of thing you can devote your attention to in the way that many of us haven’t been able to since we were kids.

Because so many of us grew up with this game at a time when baseball meant stirrups tucked into cleats, Saturday afternoons in the local park, and pizza parties at the end of the season; not the exchange of arbitration numbers, the intentional, multi-year tank jobs, the threat of minor league contraction. It was a time before even the 1994 strike, when the thought of a world without baseball was impossible.

“This device isn’t a spaceship. It’s a time machine…It takes us to a place we ache to go again.”

Rory has a particular knack for tapping that nerve. Five years ago, he started an NBA Jam tournament between 30 friends at a bar in D.C. It’s grown every year since, topping 100 people last year, stretching over six game systems and an entire afternoon. Once you understand that foundation, coupled with our particular moment in history, his suggestion to me on Friday, March 13 makes perfect sense.

Oh, right, about the baseball. The regular season is just two weeks plus two weekends long, ending this Sunday. Players schedule their 12 regular season games whenever they and their opponents have time, allowing flexibility amid an ever-shifting load of responsibilities. There’s a quirk in the particular game we use that lends some amount of lag to Player 2, or whoever the road team is. The result is a pronounced home field advantage which, actually, is kind of cool. Road wins are at a true premium and it will reward the better records come the playoff ladder, where everyone gets in, but division winners get a first-round bye and lower seeds have a single elimination road game. It’s going to be a big, beautiful mess.

And, sure, it doesn’t fix anything. But I’m a sportswriter—my job is never, really, to fix anything. It’s to make life a little more enjoyable a few hundred words at a time, to help give perspective and context for things that often lack them. Right now, our world misses the daily rhythms that baseball provides for so many of us. Maybe at least in some small way, the SDBL restores them, at least a little bit, at least for now.

When it’s all said and done, if enough people want to sign up (you can add your name to the waiting list here), we’ll do the whole thing over again.

Noah Frank is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C. and an adjunct professor at Loyola University Maryland.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now