FanGraphs’ Craig Edwards’ piece regarding this very same topic ran yesterday, and Craig Calcaterra’s version ran Sunday. This article was started prior to either of theirs running, so something must have been in the Craigwater.

Throughout the various drips and drabs of news regarding a potential 2020 season for baseball, the many one-, two-, or multi-state plans, one item remains a bit stickier than others: The owners want players to take an additional reduction in pay after March’s agreement to prorate player salary by games played.

While the many plans that have floated up through the media have failed to come to fruition, today’s offer from ownership to the union is expected to reflect many things: a shortened season (between 78 and 82 games), a June spring training redux, minimized travel, only in-division play (but across league lines), among other ideas, and … that pay cut from their prior agreement.

The ask from ownership isn’t a surprise; neither is the players’ bristling at the suggestion. Ownership is expected to take a relative bath on the 2020 season, with fans unlikely to be allowed to attend for much of all its attenuated length. Commissioner Rob Manfred is quoted by the Associated Press as saying:

“Our clubs rely heavily on revenue from tickets/concessions, broadcasting/media, licensing and sponsorships to pay salaries. In the absence of games, these revenue streams will be lost or substantially reduced, and clubs will not have sufficient funds to meet their financial obligations.”

Implicit in that statement is something that doesn’t get as much air when it comes to discussions of revenue within baseball. Ownership views some forms of revenue as more closely tied to what informs player salaries than others. This isn’t groundbreaking—capped leagues that share revenues with players have agreements that spell out what is “basketball/football-related revenue” and what isn’t, with revenue deemed related to the core sport being factored in at a different percentage than non-related revenue. But baseball is technically an uncapped sport, so those types of particulars are sussed out by behavior rather than language in a legal document.

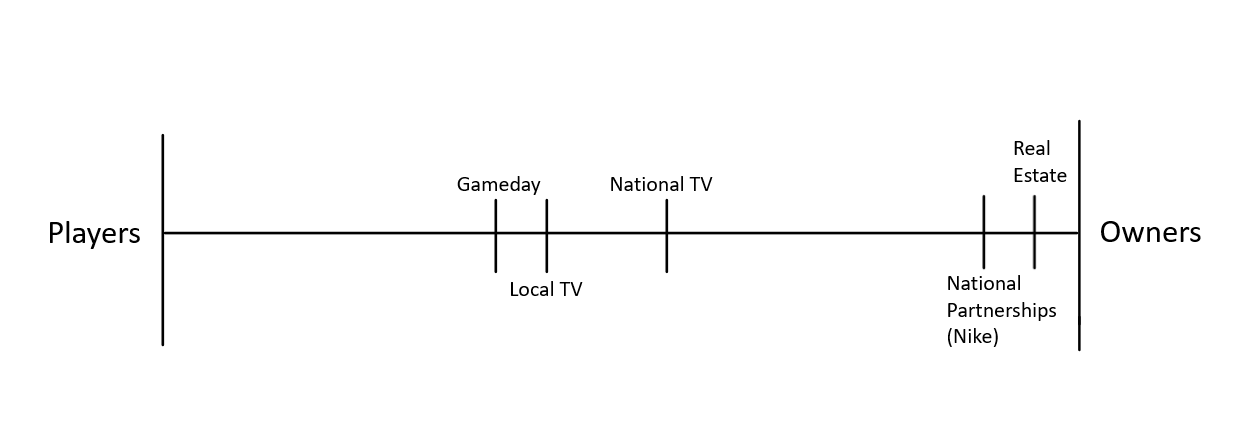

Because we don’t have the numbers to plot these things in absolute terms, it can be instructive to view these revenue streams in terms of relative distance. Some of them (local television revenue, gameday revenue) have a closer relationship to the players, in terms of how much money flows off of them to player salaries, than others (national television revenue, sale of BAMTech).

Baseball’s chart might look something like this:

Fig 1: Relationship of revenue stream flow to players and owners in terms of distance

This is not exact by any means, and does not address every major or ancillary revenue stream, but it gives you a rough idea of how the two sides see each activity—how much they might expect which streams impact on-field spending and which largely sit in ownerships’ pockets.

It’s important to note, too, that the ancillary items—those deals that wouldn’t be assumed to be “baseball-related revenue” in any type of revenue sharing agreement—are taking up bigger and bigger pieces of the pie over the last few years.

As owners come to the bargaining table seeking to renegotiate an agreement they reached in March, asking players to share in the pain, it’s worth looking at the ways in which they’ve repeatedly sought to isolate their profits over the years. They’ve done this by creating additional and enlarging current ancillary revenue streams—ones not necessarily assumed to be “baseball-related revenue” in a revenue sharing agreement—frequently known as privatizing the profits.

BAMTech Sale

Major League Baseball’s sale of BAMTech, the arm responsible for streaming content from MLB, as well as HBO, NHL, WWE, ESPN, and Disney, constituted $2.58 billion over the course of two transactions (a total of 75 percent of the company was sold to Disney). That placed its valuation at $3.75 billion at the time of the sale, the remaining 25 percent interest being held by MLB via MLB Advanced Media, and the NHL (as of 2015 the NHL held a 7-10 percent interest).

MLB Advanced Media (MLBAM) was seeded by the owners of the 30 MLB teams in 2000, each receiving an equal equity stake. The company quickly grew thanks to an increasing appetite for streaming media and a crucial geolocation patent they received in 2004. Between its founding in 2000 and the release of its first third-party client in 2005, MLBAM built out the infrastructure to stream MLB games, allowing the league to generate a revenue source for fans who were looking to more closely follow teams who weren’t in their market. By 2012 it was generating more than $600 million annually in revenues.

As MLBAM and subsequently BAMTech grew into massive revenue generators, the valuations of MLB franchises exploded (BP’s Rob Mains calculated team appreciation at 14.1 percent per year from 2010-2020). In any sort of revenue sharing agreement, the league would almost certainly attempt to exclude MLBAM and BAMTech revenue they’re still generating as non-baseball revenue, but it is difficult to ignore that MLBAM and BAMTech would not exist as constituted without MLB, and MLB would not exist without the players.

Because baseball is an uncapped sport, the idea is that anything that helps grow revenues will eventually trickle down to growing salaries for players. But while player salaries grew throughout the majority of the last two decades, they did not keep pace with MLB revenues. That is due in part to the notion that a portion of the drastic increase in revenues is attributable to streams like MLBAM, which you’ll note did not get included in Manfred’s statement above about which revenues pay salaries.

Real Estate

Baseball teams aren’t just baseball teams anymore. They’re media moguls, they’re investment holders, and, increasingly, they’re real estate companies. Not only are teams still conning counties and states into paying for stadiums, but they’re buying up the surrounding real estate, to great effect.

The Braves development of The Battery complex near Truist Park was already paying off in 2018, as the Wall Street Journal reported that Liberty Media projected a 22 percent return on the sale of three apartment buildings in the $700 million complex, but they’re also receiving rental income. That rental income is part of what drove Liberty Media’s development revenue from $8 million in 2019 to $10 million in 2020, offsetting the $2 million decline they saw in baseball revenue over the same period (a decline due primarily to unearned revenue from media rights deals).

The Braves are but one example, but the Rangers have made a similar deal in Arlington; the Cardinals have teamed up with Cordish Cos. in Ballpark Village outside of Busch Stadium; the Cubs have developed an entire real estate arm of the business that offers its services to other teams, on top of the work they’ve done in Wrigleyville around the ballpark.

While it is all but certain that some teams will lose money in 2020, the Braves’ development demonstrates how their diversified portfolio allows them to offset those losses in the meantime, and is yet another example of how teams are profiting off baseball-adjacent revenue streams that don’t have a clear path back to the players.

As Patrick Rishe, a Forbes contributor and professor at Washington University St. Louis notes, teams in a variety of sports are increasingly looking to real estate…

“…Because of revenue sharing rules that may extract a portion of venue-related revenues, being able to generate ancillary revenues from nearby real estate developments creates a flow of monies that are shielded from sharing… [and] because these ancillary developments boost the revenue-generating capabilities for teams, their ultimate franchise values appreciate more than they would without such developments.”

While baseball does not have a codified version of monies that are shielded from revenue sharing, it’s clear, based on the in-flow of money and its corresponding effect on team payroll, that the teams are behaving in a similar manner to those in leagues that have revenue-sharing agreements in place.

National Partnerships and Sponsorships

One recent example of this is the league’s pact with Nike, which not only planted a swoosh on the front of jerseys, but also a billion dollars of revenue in ownerships’ wallet over the course of the next 10 seasons. This is considered central revenue—money that the league takes in and then is split evenly amongst the 30 clubs—and thus amounts to a little more than $3 million per team, per year. A small enough amount to never have to flow towards the players, but it ends up as $33 million per team over the course of the deal. Less impactful still is the league’s deal with MGM, worth a reported $80 million over four years.

Essentially any revenue that gets distributed to the teams from the league centrally has a more distant relationship with the players than local deals. This includes national tv deals, like the $5.1 billion, seven-year deal with FOX that will end in 2028. That amounts to around $729 million to the league annually, or just over $24 million per team per year. It seems unlikely that payrolls will see a similar swell come 2022, considering ESPN’s $5.6 billion, eight-year deal that runs through 2021 did little to prevent the limited spending of the 2017-18 and 2018-19 offseasons.

***

Let’s return to Manfred’s quote from the top of the article:

“Our clubs rely heavily on revenue from tickets/concessions, broadcasting/media, licensing and sponsorships to pay salaries. In the absence of games, these revenue streams will be lost or substantially reduced, and clubs will not have sufficient funds to meet their financial obligations.”

The commissioner lays bare the totality of what I’ve described above. The revenue streams that ownership considers pertinent to payroll are gameday and local broadcast revenues. The latter will probably soon expand a touch, as the league recently “approved unanimously a revised interactive media rights agreement,” per Forbes’ Maury Brown.

Despite there being no formal revenue-sharing agreement between the league and the players, MLB owners already behave like their counterparts in the NFL and NBA in terms of how they allocate profits based on where they come from, despite the ability to earn those profits originating with the players on the field.

As ownership’s proposal is presented to the players union today, and players are asked to take a paycut within a paycut, the league and some media outlets will frame this as a question of economic feasibility. It is not a question of economic feasibility. It is also not a question of whether owners will lose a lot of money this year, because the reality is that everyone—players, owners, many of us throughout the country—will lose a lot of money this year.

It is a question of, “are the owners better off playing games without fans and paying players the agreed upon prorated salaries than playing no games at all?” Elsewhere in the country, small businesses are reopening without any guarantee of a profit, many without a likelihood of survival. And that’s if they made it to the point that they’re able to reopen.

The owners in Major League Baseball aren’t entitled to a profit just because the last few decades have provided one. Owners like to say that baseball is a business, that capital is entitled to its profits because it takes all the risks. Ownership has certainly taken the profits over these last few decades, but now that they are in question, they’re asking players to share the pain; owners seek to inoculate themselves from the very risk used to justify their percentage of the profits. More succinctly, they’ve privatized the profits, and now want to socialize the losses.

Thank you to Rob Mains for his research assistance, and to Mike Ozanian and Maury Brown of Forbes for all their research. Thanks to Patrick Dubuque for his patience.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

The difference was that back then it was the owners who had the sole power send them anywhere and the players had no say in the mattet Whatsoever.

Players were nothing but human chattel. Good times, huh? Those were the days!