Pride Nights, LGBT Nights, or similarly marketed events have slowly grown to be held by nearly every MLB team. This commonality makes social media engagement regarding the events a good barometer for the opinion of MLB fans, LGBT and not, on if such events should be held, whether they might attend those events, and if they feel the events are well-staged.

The Pride Project is the result of my research into social media engagement with and response to Pride Nights. It developed out of a project I was working on in summer 2019 attempting to quantify bias in social media regarding the Women’s World Cup. I stumbled across a group of tweets regarding an upcoming Muslim Heritage Night to be held at Oakland Coliseum, home of the A’s. The sentiments expressed were largely supportive, contradicting Twitter’s reputation as perennially caustic. I wondered, on the overarching topic of celebrating diversity, whether the general tenor of social media might diverge from what many expect.

While events like the Muslim Heritage Night that incited my inquiry are ripe for future research, the near-hegemony of Pride Nights or similar events at MLB stadiums (plus at many Minor League stadiums) made it an ideal target for research across various social media feeds. While I have personally enjoy attending past Pride Nights, I also know LGBTQ+ people who avoid sports events because they don’t feel welcome—meaning there is discourse to examine within and without the subsection of LGBT fans. That LGBT issues are frequently polarizing only accentuated the felicity of the topic—how better to test if social media is as acidic as reputed than with a frequently contested matter?

This article discusses some of my observations. You can browse the whole project at https://theprideproject.net.

The Pride Project: Promoting Inclusion in Diverse Fan Bases

Every season, most major league teams host a “Pride” game to recognize and celebrate their LGBTQ+ fans, employees, and community members. Events range from large productions with events like pre-game panels to teams simply offering a bit of swag with a special game ticket.

Some minor league teams have followed suit with big festivities (the Hartford Yard Goats, the Double-A affiliate of the Colorado Rockies, had not one but three Pride nights scheduled for the 2020 season pre-COVID-19). One minor league team, the short-season Staten Island Yankees, has hosted Pride Night since 2015 despite its parent club in the Bronx never hosting an official Pride Night.

Just as participating teams’ celebrations of their lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ+, with the plus sign indicating inclusivity) fans vary greatly, so does the reception of these events among their fanbases. The first Out at Wrigley game was two decades ago, yet professional sporting events can still be an unfriendly and uncomfortable atmosphere for many LGBTQ+ fans.

LGBTQ Pride is a polarizing topic, and that shows in fan feedback regarding Pride Night celebrations. To gauge the variations in fan responses among MLB teams and catalog those sentiments, The Pride Project analyzed more than 13,000 tweets and approximately 900 survey responses.

Who Attends Pride Night? Who Doesn’t?

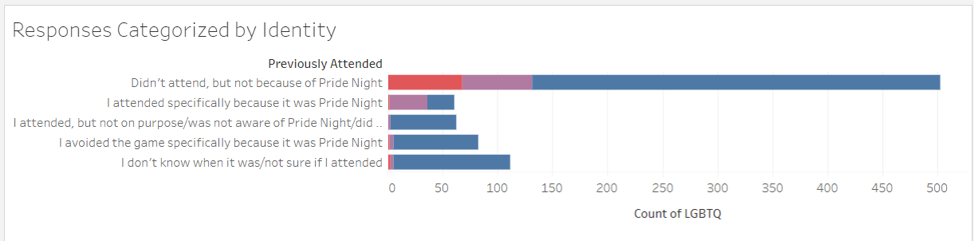

For most fans, a Pride Night celebration doesn’t influence the decision to attend a game. Those who say it does, however, overwhelmingly identify as LGBTQ+. This suggests that many teams’ Pride nights are reaching their target audience and attracting fans from the LGBTQ+ community.

The Pride Project’s data collection included a question about whether fans go out of their way to attend Pride events, purposely skip games with such a theme, or fall somewhere in the middle. Intentional avoidance was most likely among the straight, cis (cisgender/identifying with the gender assigned at birth) community.

Baseball fanbases reflect the general population in that the majority are straight and cis; thus, it’s not surprising that previous attendees were primarily not LGBTQ+. However, some still went out of their way to attend these games, despite not being part of the targeted community. In describing their reasons for attending the events, they used words like community, inclusion, acceptance, and energy.

Fans who reported that they avoided Pride games were also split. A Boston Red Sox fan who identified as LGBTQ+ raised questions about the authenticity of teams’ motives (“Are they really addressing issues or celebrating queer folks in any meaningful way? Or are they just trying to cash in?”), and straight cis fan comments ranging from apathetic (“meh”) to critical (an Atlanta Braves fan wrote: “Stupid. I don’t know why we need so many special nights if we’re all supposed to be having equality.”) Some responses were openly homophobic.

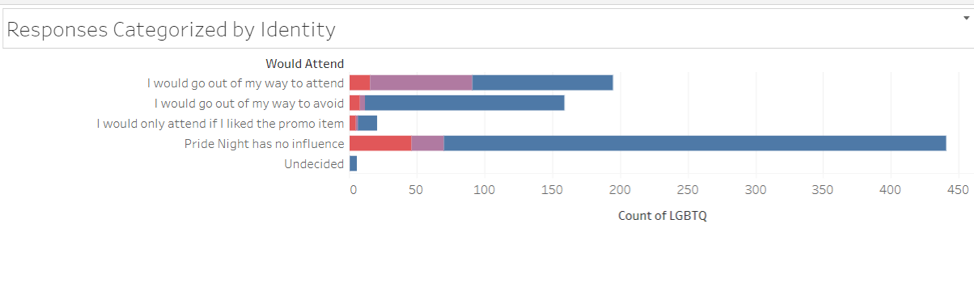

Fans fall into similar groupings when discussing future purchasing decisions.

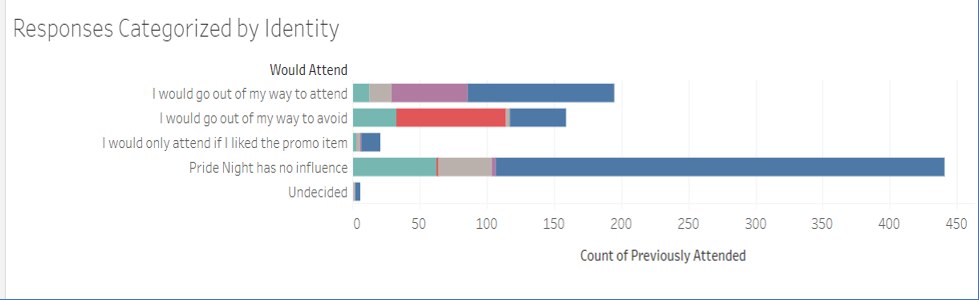

An interesting trend emerged when comparing planned future attendance with past attendance.

An interesting trend emerged when comparing planned future attendance with past attendance.

Most fans said they don’t factor in Pride Night when making purchasing decisions, but those who have attended previously indicated that they are very likely to attend again, and few who attended previously said they would go out of their way to avoid a Pride event in the future. If most fans don’t make purchasing decisions based on the Pride theme, but most fans who do attend once would attend again, it may be that exposing fans to a Pride-themed event helps create more allies. Respondents’ comments certainly suggest so. Another explanation is that previous and future attendees who are not LGBTQ were already more likely to consider themselves allies.

Responses from this group included statements like:

- “I like how the A’s are trying to encourage new fans to come to the park. Pride Night was a lot of fun with good energy.” (Oakland A’s fan)

- ”Very respectful” (Washington Nationals fan)

- “I love to show some love and support to my LGBT friends.” (Atlanta Braves fan)

While MLB fans include a dedicated base of detractors, these comments and patterns suggest that teams could build loyalty both within and without the LGBTQ+ by attracting more fans in general to Pride Night.

Pride Celebrations Are Now Expected

When the Chicago Cubs first hosted Gay Days in 2001 (later rebranded as Out at Wrigley), LGBT-centric events were controversial. In 2020, Pride Nights have become so common that not having one is what gets a team noticed. In 2019, only the Houston Astros, Texas Rangers, and New York Yankees failed to host Pride Nights. While the Yankees’ “Tribute to Stonewall” event commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots—widely regarded as the start of the gay civil rights movement—their 2020 schedule had no Pride-themed event listed before a pandemic brought the pre-season to a screeching halt.

Teams should be aware that fans are taking note, as evidenced by comments like these:

- “I like it and I wish my team hosted one” (Houston Astros fan)

- “I think it would be great. I am gay and the Astros have a lot of gay fans and have children who are fans. I’ve never heard of this in Houston and I literally watch daily.” (Houston Astros fan)

- “Important and needs to be league-wide.” (New York Yankees fan)

- “The Staten Island Yankees won all of baseball this year because they wore rainbow pinstripes” (New York Yankees fan)

Fans likewise notice a team’s level of commitment to providing visible support to LGBTQ community members, as demonstrated by general fan feedback as well as Twitter engagement. Some comments included:

- “The Angels night was a tepid disappointment, which I suppose is appropriate for them in general.” (Dodgers fan)

- “Are they really addressing issues or celebrating queer folks in any meaningful way? Or are they just trying to cash in?” (Boston Red Sox fan)

- “You don’t get to act like you’re all supportive of the LGBTQ+ community while you work with Chick-Fil-A, a.k.a a company that doesn’t want us to exist. Read the freaking room.” (New York Mets fan)

When it comes to Pride events, one of the most active and most positive voices is @Mariners, the Twitter feed of the Seattle MLB franchise, whose social media team has a reputation for clapping back at rude comments:

- “Really helpful and make me proud to be a Mariners fan!”

- “Excellent, their social media team wasn’t putting up with awful people in the comments either”

While fan enthusiasm in general tends to wane during losing seasons, some trends suggest that fans remain enthusiastic about Pride Nights regardless. The Mariners had one of the highest overall levels of fan Tweet activity and one of the highest percentages of overall positive sentiment, despite the team’s struggles on the field. Conversely, the Phillies were performing well and were in first or second place in the NL East for much of June 2019, but the team’s social media campaign for Pride Night was limited, resulting in little Twitter engagement and a lower positive:negative ratio.

The data suggests that fans will stay engaged with positive LGBTQ+-centric messaging even through losing seasons, as long as the team’s account itself is active. The team sets its tone toward LGBTQ fans, and the rest of the fanbase follows suit. Teams that wish to build truly inclusive fan bases should strive for authenticity in social media tone, with no reluctance to call out hostile fans as they see fit.

The data also suggests that the topic of Pride Night attracts at least some negative feedback, even during periods when a team’s social media engagements are generally low. It’s a predictably polarizing topic, and teams should consider the tone they want to project when they plan their responses to inevitable trolling.

The President and the Pitcher

The Pride Project conducted a sentiment analysis on the survey comments, and in the process, two commonly mentioned names emerged: Donald Trump and Sean Doolittle. The president’s name was found only in the “negative” comments group, and the pitcher’s name was found only in “positive” comments.

In recent years, the Trump administration has rolled back or attempted to roll back numerous protections for LGBTQ+ people, including antidiscrimination laws governing adoption, medical treatment, and military service. Trump is an icon for the far-right, and has been accused of fanning the flames of discrimination via actions and tweets sentduring events such as the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally and the George Floyd protests.

Sean Doolittle is a relief pitcher with the Washington Nationals, previously with the Oakland A’s. Doolittle and his wife Eireann Dolan have been prominent and vocal allies of the LGBTQ+ community, particularly youth. Every year, the couple actively participate in Pride festivities; backlash about the Athletics’ first Pride Night in 2015 prompted them to buy 900 game tickets for LGBTQ+ youth. Doolittle is also one of a handful of white baseball players who have openly expressed support for the #BlackLivesMatter movement.

Comments that mention either of these men by name include:

- “Very positive. Great for the sport and inclusivity. Having an ally in Sean Doolittle is great. Athletes tend to not be very liberal.” (Oakland A’s fan)

- “Disgusting. TRUMP 2020!” (Atlanta Braves fan)

- “I love that my team tries to make everyone feel welcome. Pride Night is a big part of that. I miss Sean Doolittle and Eireann Dolan. They were huge advocates and allies of LGBTQ youth. Maybe one day this will help a player feel comfortable coming out. I love that we have about a million different theme nights and we recognize everyone. Go A’s! #rootedInOakland” (Oakland A’s fan)

- “Good! I like when players get involved too, like Sean Doolittle.” (Washington Nationals fan)

- “All f****s Go Trump!” (Baltimore Orioles fan)

- “it’s a good start. I especially appreciate how Sean Doolittle reaches out to the LGBTQ community and youth groups.” (Washington Nationals fan)

Comments and tweets from A’s and Nationals fans on the subject of Pride rated “highly positive” overall, and while some of that enthusiasm may be rooted in general area demographics, these teams’ nearest neighbors—San Francisco and Baltimore—did not have similarly high ratings (meaning location isn’t the only factor). A celebrity endorsement carries a lot of weight; a player as active participant can influence fan attitudes.

Words matter, and politicians, athletes, and celebrities all wield large megaphones. Players who want to use their platforms can have a lot of impact.

Why It All Matters

There’s an obvious financial interest for any team to market toward LGBTQ fans—more fans means more money, and connecting with an underserved demographic with a proven appetite for the product can be an excellent way to drive more sales. But there’s also a more human level, and some fan comments drive home this point:

- “Great way to be inclusive and celebrate a portion of society that’s been persecuted and shamed. Using sports to help normalize a marginalized group that’s targeted by toxic masculinity is great and hopefully leads the next gen to be better than we are” (Milwaukee Brewers fan)

- “I think they’re incredible and opens up MLB players to talk about their sexuality in a healthy and supportive way.” (New York Mets fan)

- “I love it. I think it’s an important even for the MLB to promote and hope that it grows in the future to the point where even players feel comfortable enough to let their own sexualities be known” (Arizona Diamondbacks fan)

In their ballparks, teams should strive to make every person in a community feel as welcome as the next guest, but as a society we aren’t there yet. Pride Nights bring MLB a step closer to that goal.

***

Technique

The Pride Project is built from approximately 13,000 tweets, collected via Twitter’s API and API Sandbox and via the ScraPy library for Python. The survey component generated about 900 responses after anonymous distribution in team-agnostic Reddit, Twitter and Facebook feeds (for example, /r/baseball instead of, say, /r/dodgers).

The dataset has some limitations, particularly with the small sample size of the survey and the low tweet activity referencing some teams.

Data cleaning and processing tools were Python, Pandas, Scikit-learn, Vader, and SpaCy; visualizations were created with Tableau, Flourish, and Matplotlib.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now