On June 10, the evening of the MLB Draft, Commissioner Rob Manfred read a statement in support of Black Lives Matter. Each team’s general manager/president of baseball operations/head honcho held a sign on their live feed that read, “Black Lives Matter, United for Change.” Since games have resumed, players are now “permitted” to kneel in support of Black Lives Matter, and pitcher’s mounds displayed BLM emblems (before giving way to advertisements).

As Baseball Prospectus’ Shakeia Taylor wrote, MLB’s words and actions accomplish very little. “What MLB’s Black Lives Matter campaign lacks is bite. It lacks substance and effort. It lacks … a plan of action. T-shirts, pre-anthem kneeling, a suddenly ‘woke’ social media team, and a video voiced by a legendary Black actor are not actually effective in fighting systemic racism.” Instead of performance, MLB could make a more significant difference by evaluating their own practices that repress Black players.

As one of the authors of this article discovered, white players are promoted through the minors at a 3-4% higher rate than their BIPOC counterparts. To discern why this occurs, it’s important to take a more granular look at the underlying biases—specifically regarding positions on the field—that contribute to promotion bias as well as the overall dwindling participation of Black players in MLB.

In studying where players of different races end up on the field, we found three major trends. One is that Black players have been systematically locked out of the catching position to an extraordinary degree. Two, Black players everywhere else on the field tend to get pushed into the outfield, even those that start out at theoretically more valuable positions in the infield (shortstop, second base). Finally, and most depressingly, these barriers to equitable participation of Black players have not improved at all in the last decade, despite the movement towards a theoretically more objective player-evaluation methodology that should have cut through racial biases.

Before we get to the results, here are a few quick notes on our methodology. As in a previous study, we used invaluable race/ethnicity data provided by Mark Armour and Daniel Levitt. (Their data only covers players who made the majors, which is an important limitation.) They broke players down into one of four categories: African-American, Asian, Latino, and White. Racial identity is more complex than any single categorization can encompass (for example, Afro-Latino people make up a significant subset of the players in MLB), but this grouping is a first step towards understanding biases in MLB. The data set uses African-American/Canadian as separate from Latino, and Afro-Latino players are classified as Latino for the purposes of the data set and this article.

We broke down each player and season by the position they spent the majority of their defensive time at. This method flattens versatile players to their most common spot on the field. We also examined the position each player debuted at (where they spent their first season in the majors). For this study, we excluded pitchers; while there are racial biases in whether players become pitchers vs. position players, we wanted to focus only on the latter group.

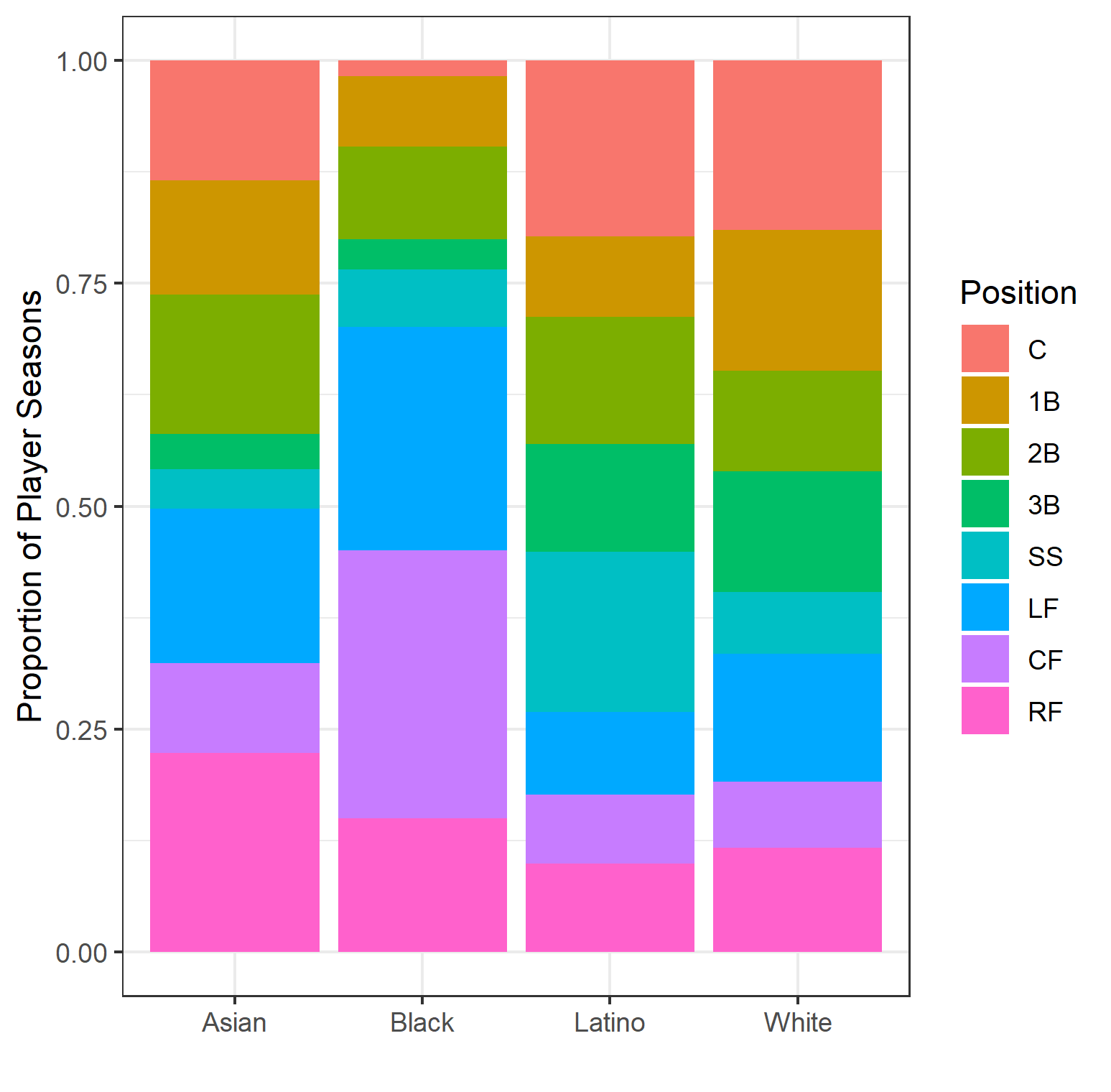

Two major disparities jump out from this chart. The most glaring concerns a lack of Black catchers—there are about one-tenth as many Black catchers as there should be (~2%), based on the proportion of catchers among other races (~20%). Second is the overwhelming majority of Black outfielders. While outfielders compose about 25-40% of the player-seasons among other races, they make up about 70% of the Black players in baseball. We’ll treat these two disparities in the following sections.

Why Are There So Few Black Catchers?

On September 23, 2017, A’s catcher Bruce Maxwell knelt during the national anthem in support of Black Lives Matter. This act was somewhat more common in the NFL, albeit no less controversial, where Colin Kaepernick and Eric Reid led a movement that spread to nearly all 32 teams. In MLB, though, Maxwell knelt alone. A few weeks ago, ESPN’s Howard Bryant profiled his exile from MLB. (Coincidentally, he signed with the Mets a few weeks later.)

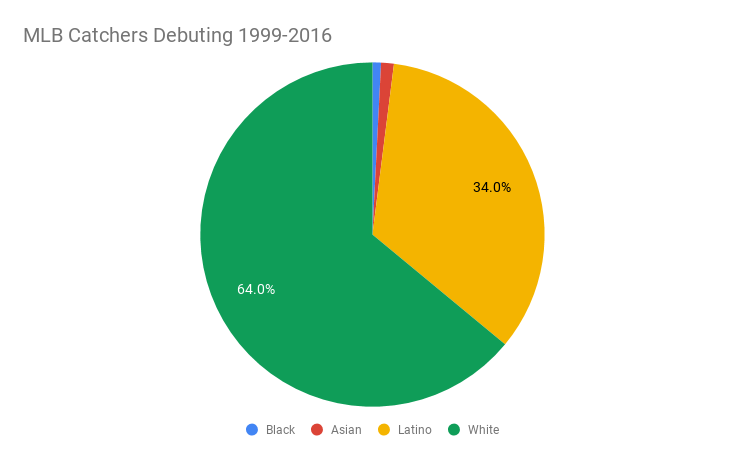

Even without kneeling and the saga that ensued, Maxwell is unlike any of his MLB peers. According to our data, which runs through 2016, he is the only Black catcher to play in MLB who debuted after 2009, and one of only two who debuted after 1999.

The overall percentage of Black players in MLB has dwindled from 13.6-6.7% over this timeframe, but clearly there is not even representation at all positions, and Black catchers in MLB have all but disappeared.

In April, The Undefeated’s Claire Smith wrote an excellent piece exploring the absence of Black catchers. She described many potential reasons in her article, including unequal access to catching equipment, biases of both old-school and new-school scouting methods, and stereotypes about tools needed for each position.

While all 30 MLB organizations share some blame for the dearth of Black catchers, the problem has roots that reach into collegiate, high school, and even youth leagues. Plenty of players transition off of catching in the minors, but very few switch to catcher from other positions. More than likely, if a player isn’t drafted or signed as a catcher, they’re never going to become one (with a few exceptions such as Robinson Chirinos and Isiah Kiner-Falefa). Major League Baseball teams may be less likely to draft Black catchers for several of Smith’s aforementioned reasons, but a big part of the problem is that many Black players don’t reach draft eligibility as catchers in the first place. To foster real, genuine change, MLB will not only have to address their own scouting, drafting, and development systems, but also work with their feeder leagues– including the NCAA, Little League, and showcase circuit promoters– to encourage better positional representation at all levels.

Athletic Black Players Are Funneled Into The Outfield

The flipside of the nearly-complete absence of Black catchers is an overabundance of players in the outfield. That comports with stereotypes of Black players expressed in scouting reports and evaluations: mainly that they are “speedy” but “raw,” and thus perhaps unsuitable for the infield.

Black players are especially prevalent in center field. Considering the athleticism required to play there, there ought to be many more Black shortstops than there are, but instead they are significantly under-represented at that position.

Black players are significantly more likely to debut in the infield than they are to stick there. It’s normal for players to move towards the outfield as they get older, slower and less defensively proficient, but the proportion of white outfielders remains basically the same in debut seasons and full careers. Black players, by contrast, are significantly more likely to begin at second base and shortstop and then later get moved out to center or left field.

The skew towards outfielders has other implications for Black players in the league. As Cameron Maybin observed in an interview with Howard Bryant, “if a guy shows any athleticism, he gets pushed to the outfield, so we’re really competing against each other for the same jobs.” Concentrating all the players of one race into a handful of positions limits their opportunities. Because two-thirds of outfield positions are not especially defensively valuable, the practice also limits wages. A great shortstop is in line for a significantly larger payday than a great left fielder.

And since players tend to move down the defensive spectrum as they get older, the bias towards the outfield may also limit Black players’ longevity in the league. A player who starts at shortstop can move to third base before transitioning into a corner outfield spot or first base. But a player who starts in left or right field has nowhere left to go, so without a standout bat, they may end up out of the league altogether.

***

You might expect that these positional disparities would have started to disappear in recent years. With the rise of sabermetrics and a focus on data over ill-defined and empirically-unsupported stereotypes, Black shortstops (for example) should have ceased being unjustly shifted into the outfield.

Unfortunately, the statistics show that biases against Black catchers and towards Black outfielders have persisted. In the last 10 seasons (2010-2019), there were fewer Black player-seasons at backstop than in the 10 years prior (2000-2009). The same regression appears for the outfield: Black players spent more time in the three outfield spots in the last 10 years than in the decade before.

To some extent, racial biases in positions occur before front offices ever get involved. Racist decisions made when future major leaguers are children may push them onto athletic tracks that result in their shunting to specific positions. But that does not absolve front offices of a responsibility to combat those decisions. If the game is to improve its representation and eliminate racism, it has to start with decision-makers taking small and large steps alike, from asking why a Black prospect shouldn’t try their hand at catching to encouraging feeder leagues (like the NCAA) to take on their own racial biases.

There is also a performance-based argument for front offices to take on racism (although that shouldn’t be nearly as persuasive as the moral imperative). It’s undoubtedly the case that plenty of Black outfielders would have made more valuable shortstops, catchers, or second basemen (or pitchers, for that matter). By never allowing them that chance, teams have gravely misallocated their talent and likely wasted the abilities of some of their best players.

Some of baseball’s more pernicious racial disparities ultimately stem from these positional imbalances. For example, managers are overwhelmingly drawn from the ranks of former catchers, so decisions about where on the field to put a promising prospect can manifest decades later as a severe paucity of Black coaches and skippers. The only way to solve this issue and others is to correct the problem at the source: when Black players are funneled away from their natural positions on the diamond and into the outfield. That’s a job teams, front offices, scouts, and coaches at all levels ought to take seriously, for the good of the game.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

But it really does. You just don't start becoming a catcher at age 18 and have any success at it. Nothing MLB realistically can do about it. And that might be a good thing for the black athletes who might have been catchers but play other positions instead; catchers probably make less and have shorter careers than any other positions.

Russell Martin, the Hall of Fame-caliber catcher who played for 14 years and made more than $100 million, would like a word. He converted to C from 3B at around age 20.

In all seriousness, I know that the conventional wisdom is that catcher takes a long time to learn and perhaps there are more catcher-conversion failures that we don't hear about. But there also seem to be cases like Martin and Isiah Kiner-Falefa who can convert and in some cases even become better players for it.

A separate but related question is the idea of conversions to catcher once players pass into the MLB coaching sphere. I would think we would need more data than is available, I would like to know who usually initiates them, conversion success rates (and what defines success?), ages, race/ethnicity and quite a bit more.

And Russell Martin as a HOF case, ehh? Not convinced --- you would be giving a lot of weight to the newer fielding stats to get him there, wouldn't you.

It is not as uncomon as you make it out to be.

To clarify, does this suggest Black players get shifted at the lower levels or after MLB debut? In other words, were they counted as 2B/SS in the chart above, then later moved to CF?

Seriously, do you even care that a bunch of us don’t care for this stuff? I know your standard reply is “Well, then, don’t read it,” but these articles are taking up money and space that could have been spent on articles about actual baseball and not social engineering.

What's difficult for me to understand or empathize with is a reader who says, "Please challenge my assumptions on platooning or the bunt or the shift or if Mike Trout is as good as he looks or if the ball is juiced but don't you DARE ask me to have the same open mind about the following list of baseball topics." That bifurcation is not on us to interrogate.

Finally, as someone who has commissioned literally thousands of articles for this site, who has edited the site and the books, I can attest that when we have a good story we don't kick another good one out the door. No publication does that and we don't. We just make room for one more. Whatever you're here for, we publish the same amount of it we would regardless of what appears in the commentary section.

Russell Martin is from Canada. While he may have converted from 3B later, could he have had more exposure to C growing up?

I know there's no good way to separate Latino and Afro-Latino, but I remember the days of Manny Sanguillen, Ellie Rodriguez, and Paul Casanova, and wonder if the same effect has been happening, just more invisibly.

1. Obviously racism exists

2. Here is a racial disparity

3. Racism must be the explanation

Hope this helps.

There are few Black catchers. There are (comparatively) many Black outfielders. And overall, the percentage of Major League players who are are Black has declined significantly over the past few decades. All of this is true. But these facts are not proof of racial bias, and the article offers little else other than to assert over and over again on this flimsy evidence that (White) baseball is guilty of a grave injustice.

The article says nothing, because it knows nothing, about where individual players might actually want to play. It says nothing, because it doesn't want to know anything, about how center fielders are paid compared to catchers. It ignores the fact that many Black kids seem to be choosing other sports or career paths instead of baseball -- or that other people of color might be competing effectively for the same spots. It implies that the players themselves should perceive a great injustice -- even though there is no evidence that any of them do.

(Cameron Maybin's statement is only true of all the players -- they are competing against each other for the same jobs. We knew that already. And is the other going to accuse Maybin of racist language for saying that Blacks who play the outfield have shown "athleticism"?)

On this flimsy evidence, we get a lot of unjustified phrases like "practices that repress Black players," "systematically locked out," "gravely misallocated their talent," and "funneled away from their natural positions ..." This is becoming all to common these days. We don't have to prove anything, we just use a bunch of loaded phrases and defy anyone to challenge our point of view.

Bad writing. Black folks have a plenty uphill battle as it is. We don't need you picking fights for us where there really aren't any. We're doing just fine in baseball. Focus on helping us control the police forces and the really important stuff, or just write about baseball.

This is exactly what you saw with black quarterbacks in the NFL for years - black athletes who were successful college QBs were pre-emptively moved off the position for WR roles, often being drafted at a position they had never played, in the perception that they could not handle the complexity of the NFL playbook and QB role, but that the athleticism that had let them succeed as QBs 'despite that' would allow them to flourish at the athletically-demanding WR position.

It's only very recently - with guys like Mahomes, Newton, Wilson, etc - that NFL teams allowed these guys to even attempt to stick at the QB position. Warren Moon had to go demonstrate that he was the best QB in the history of the CFL for an extensive period to get a chance at an NFL QB job. The racism is usually unconscious, but it is in the perception of what the player is capable of or CAN BECOME capable of, because players are pushed into roles in development based on their perceived potential in most cases.

The author didn't even attempt to make the African-American quarterback parallel to the catching position. The people quoted in the article didn't say they wanted to play catcher and were told no.

It's quite possible that African-American youths look up to African-American baseball players, see that they don't usually play catcher and want to play the positions they typically do play. But that doesn't establish a racist reason for the lack of African-American catchers.

Let's suppose that a coach sees a young man and sees that he is the fastest player on the field. Is it racist to think that that player's speed would be more valuable at another position? I can imagine a coach leaning in that direction no matter the race. This article assumes racism from the fact that African-American athletes are underrepresented at the position without evidence.

1. Obviously racism exists

2. Here is a racial disparity

3. Racism must be the explanation

Say there’s an objective rating on a 1-10 scale

Player A

3B 6

LF 9

Player B

3B 5

LF 5

Player C

3B 9

LF 6

If you’re choosing from A and B, A (more athletic) plays LF and B plays 3B.

If you’re choosing from B and C, B plays LF and C (more athletic) plays 3B

3B

With the African-American quarterback situation, we have documented evidence of people saying the position was off limits for various reasons, not the least of which was the ugly conclusion that they didn't think African-Americans had the mental capacity to play the position, or that they thought their fanbase couldn't handle the fact that an African-American would be in such a prominent position on the field.

I've never seen anything like this in regards to the catcher position. I didn't play major league baseball, or even in college, but if this is something that's rooted in youth sports, I can tell you the overwhelming majority of people, regardless of color, have no interest in catching because of the wear and tear it takes on your body. I remember very clearly when I put on the tools of ignorance, that people looked at me like I was crazy.

Isn't it just possible that African-Americans, by and large, just don't want to play catcher? And that they are the smart ones?

If anyone in the comments wants to mess around with this sort of data on their own time, I know Out of the Park Baseball has this sort of information this fairly easily available in their master.csv file (historical for everyone who reached MLB). It's not exactly the same as the stuff they published, but it's something that's easily manipulable and can be combined with other databases as all major "playerID" values are contained in the same place the ethnicity tag is given.

I've had some fun messing around with it (though I'm not sure about the rights issues for actually publishing anything derived from it).

Do we really have a large enough dataset? At least with Catchers, we're dealing with such a small sample that one positive outlier would randomly make the data would look dramatically different without changing any of the underlying fundamentals. I think we at some point really do need minor league data for these analyses.

Of course, it's easy for me to sit here and demand someone else undertake a massive new project to categorize every player who reached AA or AAA in the last 20 years but I think that's really the dataset we need.