This article was originally published on June 12.

As related by Rob Arthur in his column last week, “Moonshot: Baseball Ought to Confront Its Own Racism,” the designers of the baseball simulation game Out of the Park were confronted with a problem: Negative personality traits were disproportionately assigned to players of color, while positive traits and captaincy were more likely to be attached to white ballplayers. In a forum post, long-time developer Markus Heinsohn responded to the feedback, declaring that the root of the problem lay in old code, the effects were unintentional, and would be remedied in the next content patch.

Before Heinsohn’s apology, however, there was a legitimate question of how the video game arrived in this state. After all, as Alex Speier reported for the Boston Globe Wednesday, racism remains entrenched in the baseball scouting arena, and one could argue that OOTP’s inequality in character evaluation is an extremely authentic simulation of the realities of scouting. Video games as an industry has struggled with racial stereotyping and representation for as long as the medium has been capable of graphically depicting race, and in some cases even before that.

***

It’s a particularly thorny issue for simulation games like Out of the Park, because it isn’t always readily clear how a game should represent historic injustice. One example that stumbled into controversy upon release was the 2008 game, Sid Meier’s Civilization IV: Colonization. A conversion of the wildly successful empire-building series, Colonization gives the player control of a European colonizer establishing, and eventually commandeering, New World settlements, wresting control of territory from the native population. The criticism surrounding the game was inspired primarily by Ben Fritz, then editor of Variety’s video-game vertical, on the idea that a game could be made to celebrate such an evil historical moment. The response from angry internet commenters can be distilled into two common themes: “Colonization happened, stop trying to whitewash history” and “Media has always depicted awful things in movies/stories/games, storytelling isn’t glorification.” Are we saying that we shouldn’t have movies like Downfall anymore? Are we to throw out all unpleasant history?

The latter argument lives on, healthier than ever, in the debate over whether video games can be apolitical. Certainly, many people want them to be; video games are, after all, an escape, and in their infancy often were apolitical, because they were arcade experiences that lacked the resources to tell even a simple story. But even comparing video games to movies (something the video game industry itself has always sought to do) is flawed, because there’s two crucial distinctions: Video games demand interactivity, and they contain win and failure states. A game wants you to do a particular thing; it does not say Native Americans were killed, it asks you to kill them. To win at Colonization, you as the player must fulfill a certain set of conditions, which by being necessary, take on a moral capacity. Values are assigned. You can choose to be nice to the natives and not encroach on their territory, yes, but you are no longer playing a game at that point.

According to some, mere depictions of racism are not racist, making, in their minds, historical simulations like Colonization acceptable. It’s a common mindset because, particularly in America, culture is obsessed with the concept of motivation. It’s why so many recoil at the idea that someone could be called a racist, and that being addressed as such is very nearly as immoral as practicing racism itself. In the OOTP forum linked above, when the data was revealed, almost instantly the reaction was: There’s no way this could be intentional. As if this made it less harmful. Some people are bad—some other people—but it’s a few bad apples (you know the old quote, “one bad apple sits harmlessly among the bunch”). Only a few people actually want to be racist on purpose.

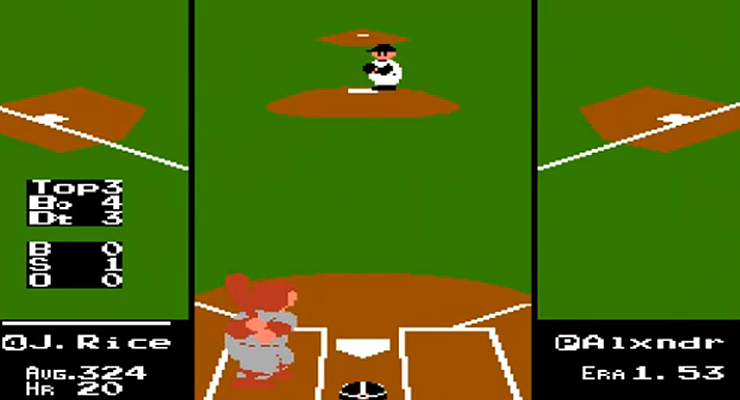

The “simulations have to be as accurate as possible” argument fails on two counts. One, they never can be; technological and human restraints will never allow a perfect simulation. (In the popular ‘80s NES game R.B.I. Baseball, African American players appear caucasian, due to the limits on how many colors the system could display on-screen.) And once that’s true, the decision over what gets cut, either to make a game possible or make it fun, introduces bias. The other is that the designers themselves back away when they get too close. Colonization curtailed a crucial element to its depiction of history, removing the slave trade, the system underpinning the entire colonial project the game represents. Replicating a world, but only partially, is not an act of objectivity.

The counterarguments to Ben Fritz are correct about one thing: It would be impossible to make an apolitical version of Colonization. It tells only one side of the story; the native cultures are non-playable characters. But that story can and should be told with context, to make it clear what mastery of the game, and its systems, means. This is not to say there should never be violence in video games, or evil. It means we can’t duplicate existing evils, free of context, as if that’s the only way it can be.

***

We don’t know how much of Out of the Park’s systemic racism was due to random chance and how much was from faithful replication, and it’s an indictment on the sport that it’s impossible to tell. Either way, Heinsohn’s solution was the correct one. It would have been possible to say that the values should remain, given what real baseball is like, with the proper contextualization to make the player understand that they were operating a corrupted machine. But removing that element, and simming a better baseball than the one that exists, is equally valid and far easier. Perhaps eventually the real baseball will live up to the decision.

Why is this essay published at a baseball website? Because baseball is a video game, played by LARPers. Like video games, the construction of baseball is entirely a construction of systems, of prohibited and rewarded actions, a formula that takes in intent and spits out results—some lionized, some derided. We celebrate the people and corporations that best navigate those systems, reward them and reward ourselves for rewarding them. Sports are, after all, the least objective history.

Racism in baseball is typically portrayed as personal, like Adam Jones being subjected to the hospitality of Fenway, the image of the vitriolic rather than the complicit. Systems don’t make good stories; redlining lacks drama. But systemic racism is just as present in the game as it is elsewhere, and it’s not as neatly symbolized as Cap Anson and his twirled, waxed mustache. It’s present in the cost of travel teams for young ballplayers, and the selective bias introduced by existing economic inequality. It’s in the lack of green spaces in America’s urban centers, limiting opportunities for children to develop, and the development of roads that have killed the stickball workaround of generations past. It’s present in the power structures of coaches and scouts, access to equal nutrition, ability to play sports after school instead of work. It’s particularly present in the upper levels of baseball, nearly devoid of BIPOC from coaching to management to ownership.

And it’s present in statements like this one, spiritually identical to the Gushers Tweet, promising to make a promise:

All while taking long enough to have developed a plan to make actual, specific change.

It’s no one person’s fault that these forces exist to restrict the access of Black people and other minorities to the sport. Some of those systems were created by intentional racism, some were not. It doesn’t really matter. They need to be addressed, and in order for them to be addressed their perpetuation of (and inaction toward) past injustices must also be addressed. People who make games make mistakes. They put the bases too far apart, or include a game-breaking bug, or thoughtlessly propagate existing racial stereotypes through invisible rules and laws. When it happens, they should apologize, fix the problem as quickly as possible, and if they made money by hurting people, give money back to the people they hurt.

What they shouldn’t do is shrug their shoulders and say, “that’s just the way it is.” Or show support on social media, have a theme night, and ignore the reasons that things got this way. Major League Baseball can’t take this situation, look at its own foundational race problem, and claim it’ll try to make it right. Baseball is already idealized, already designed to be fair. It’s not supposed to be realistic. It needs to be even better than real.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

This is nothing like the "How Civ treats colonialism" example because that's an issue that merely concerns interpreting how games use history not misrepresenting basic factual claims.

The twitter thread that gave birth to this article starts off by live tweeting a half assed pivot table combined with commentary like ("hey @ootpbaseball

what are your thoughts on race science"). This is the sort of thing any editor should reject as an insufficient replacement for an actual argument. The thread's author (and people responding) makes clear that he believes these are essentially hand coded values based on the biases of the creator.

You shouldn't be signal boosting such a low effort attempt at calling someone a bigot.

It's not even an accurate representation of the data: OOTP doesn't assign "personality traits," it assigns random values (weighted by player position) to 5 separate personality attributes and traits are defined as the combination of usually 2 or 3 traits (the full definition of which one can always find online). I'd have loved to see a high effort article on this topic that attempted to find what correlated with the in game personality traits even if such a thing would uncover genuine bias and not merely a null effect.

"Before Heinsohn’s apology, however, there was a legitimate question of how the video game arrived in this state"

With all due respect, that's simply not true. It never made conceptual sense that a small indie developer would be hand coding thousands of players a year. It was also not reasonable to assume, before trying to account for ANY other possible explanations, that the game wrote an algorithm that actively attempted to generate new players based on prejudicial stereotypes about players from specific countries or of specific skin colors.

We don’t know how much of Out of the Park’s systemic racism was due to random chance and how much was from faithful replication

You would know the answer if you took time to do the work. Uncritically accepting a semi viral twitter thread on a topical subject is how disinformation spreads.