This article was originally published on Jan. 10.

In the puzzling maelstrom of free agency, it can be hard to gauge what teams see as valuable in a player. When Zack Wheeler signed for $118 million earlier this offseason, for example, some pundits greeted the move with scorn because of his limited innings totals and close to league average ERA. Wheeler’s contract blew past the crowd’s best estimate for what he would receive and some expert guesses as well. What did Philadelphia see in him that caused them to offer so much?

In an age where a few teams are light-years ahead of the public consensus, it’s tempting to throw our hands up and give the Phillies the benefit of the doubt. But we can do better. Last week, I showed off a method to measure how the league values free agents. By tracing the contract values awarded to each player to their performance characteristics, I showed that teams started paying more for catcher framing just a couple of years after it was discovered.

This week, I want to take a look at the players like Wheeler with a mismatch between some measures of their production and the high dollar totals they eventually receive. It turns out that in many cases the gap may come down to the way teams are prioritizing the intrinsic characteristics of hitters and pitchers more than gaudy rate stats or inflated home run counts.

Intrinsic characteristics aren’t what you see in the box score. Instead, they come from the introduction of two new datasets in baseball—PitchF/X for pitching, and Statcast (but really its batted ball tracking component, Trackman) for hitting. Before PitchF/X and Trackman, viewers could see what a player did (the number of home runs they hit or allowed, their ERA or OPS) but not how they did it. All of a sudden, analysts could examine the way pitchers threw the ball or the angles and speeds with which sluggers hit it. These technologies allowed for a look behind the curtain into the process of playing baseball, instead of just its output.

I call these data points intrinsic because they reflect aspects of player performance that are unlikely to significantly change from season to season (except because of injuries and aging). Pitchers don’t often gain or lose two mph on their fastballs; when they do, it’s a major story. Batters can adjust their swings and launch angles, but their exit velocity rarely spikes enough to give them a fundamentally different offensive profile.

And because of that stability, intrinsic characteristics help predict player performance—in some cases, even better than the player’s own past performance. It stands to reason that if teams are paying attention to the data coming from PitchF/X and Statcast, they may be guiding their contract decisions less by how many innings a starter has turned in or a third baseman’s slugging percentage and more by the pitches they throw or the exit velocities they generate.

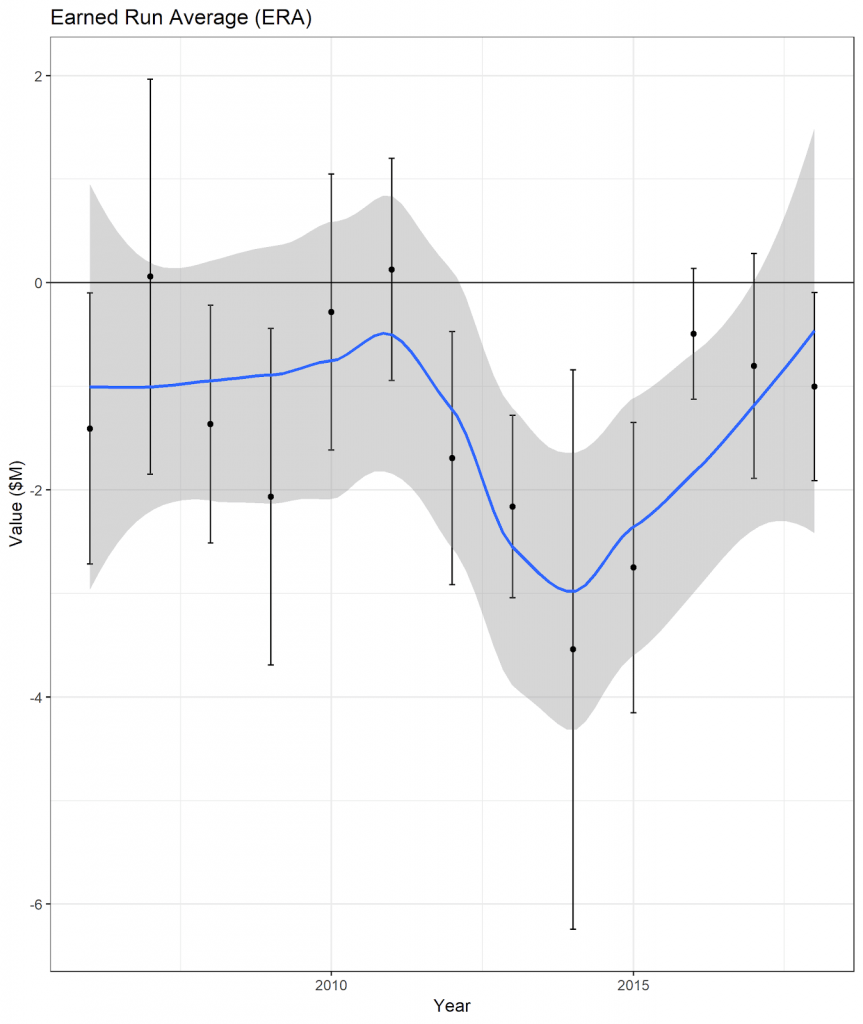

To start, let’s look at how much teams have paid for one run’s worth of ERA (examining starting pitchers only and their ERAs in the year preceding free agency). Briefly, I regressed the average annual value of the contracts awarded each season by the player’s performance in the preceding year (for more details, see last week’s article). Lower ERAs are better, so the more negative the connection is between ERA and average annual value, the more valuable front offices have perceived ERA to be.

While there is some fluctuation over the years, by and large teams have bought ERA at a rate of ~$1-3 million in AAV per run. A great starter might therefore receive $6 million per year more than one with a below-average ERA. (The great starter will likely also get paid more per year thanks to more innings pitched, more strikeouts, and other factors working in his favor, so this does not explain the full gap in earnings).

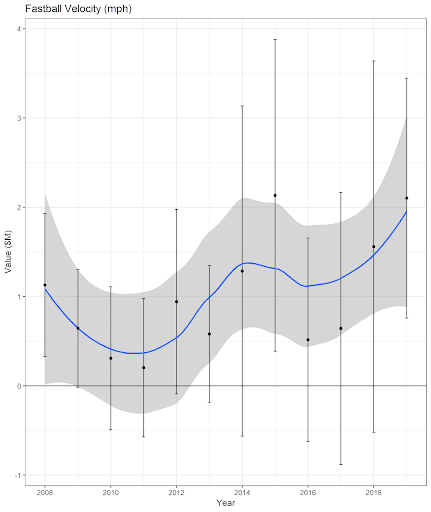

ERA is a measure of performance, however, not process. Fastball velocity is sometimes every bit as predictive (and perhaps more) than what a starter did in the previous few seasons. Perhaps recognizing that, teams are paying more than they used to for one mph of speed on the heater.

The data within a single year is noisy, but on average free agents have reaped increasing salaries for throwing faster fastballs over the years. From 2008-2013, teams rewarded one extra mph with a $0.6M boost in contract value, but from 2014 onward, they paid more than twice as much per tick ($1.4M). In fact, in the last five years, fastball velocity has earned a higher premium than ERA.

Wheeler is an example of this pattern in action: he may have posted fairly mediocre runs allowed averages, but he boasts a 97 mph fastball that puts him among the elite for starting pitchers. (A closer look at Wheeler’s resume using a more advanced statistic like Deserved Run Average—which seems to align better with how teams are paying players recently—shows that he was a significantly above-average pitcher in the last two years.)

A similar pattern has unfolded for hitters in a much more rapid timespan. While teams have had individual Trackman units for some time, it wasn’t until Statcast came onto the scene in 2015 that we had league-wide numbers. It quickly became apparent that one of the most important descriptions of a hitter’s potential was exit velocity: hitters with more of it do better. Bad luck or BABIP instability can muffle the signal of a batter’s skill, but exit velocity is almost purely a consequence of the hitter’s strength and ability to put the sweet spot on the baseball. And like fastball velocity, exit velocity can be incredibly predictive in even the most miniscule doses.

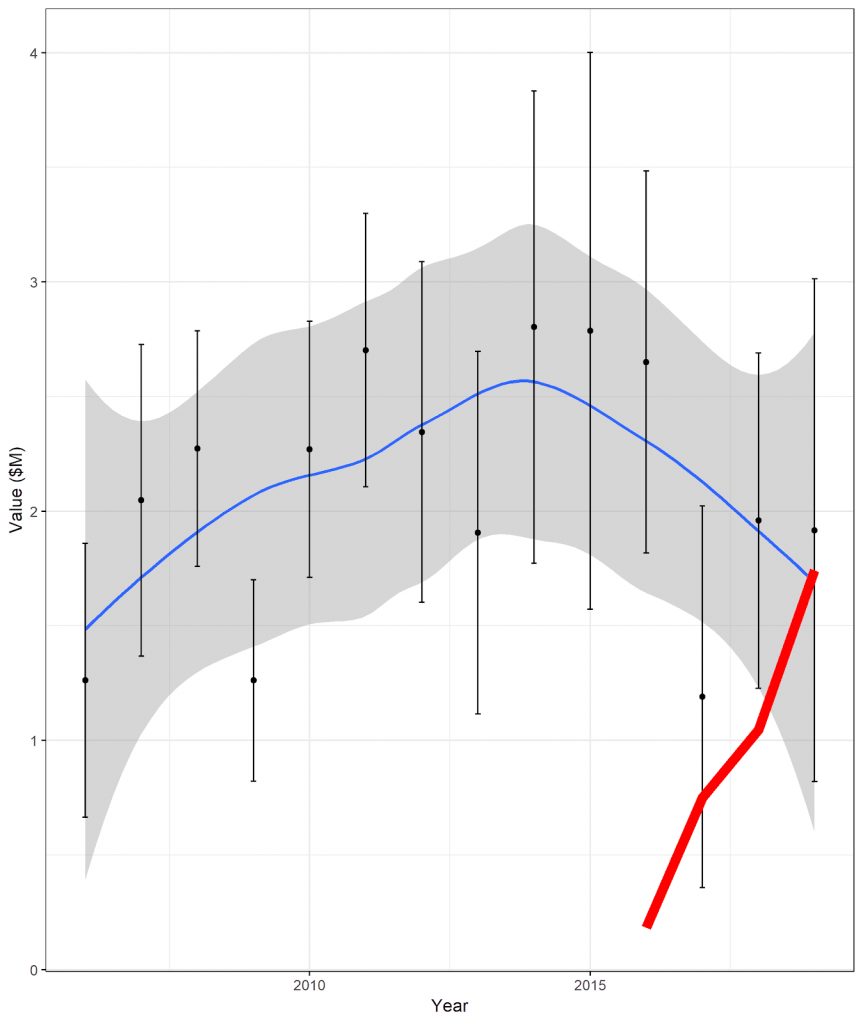

Here’s how teams have paid for one standard deviation of OPS (the blue curve; this equates to approximately 150 points) compared to one standard deviation of average exit velocity (the red line; about four mph).

OPS has a gradual arc shape to it, with values between $1-3 million per year. The contrast with how front offices pay for exit velocity is huge, however, with EV exhibiting a massive spike in the four offseasons that data has been available. Exit velocity has gone from practically irrelevant (in the first season it was available to the public) to about equal to OPS last year—a decent measure of a hitter’s overall offensive performance. Without the full 2019-2020 offseason on the books, I can’t say what has happened this winter, but it seems likely that exit velocity will eclipse OPS in the near future, if it hasn’t already.

What exit velocity and fastball heat have in common is that they both measure something core to the player, a characteristic that is unlikely to change overnight. Training and development can improve these skills, but for free agents with years of service time under their belt, they are unlikely to gain several mph in either statistic. Of course, a hitter can fluke his way into a good OPS with a bit of batted ball luck, or a pitcher can maximize their performance with runners on base to earn a good ERA, but neither performance is likely to continue without the requisite underlying statistics.

What this analysis of the free agent market shows is that teams are shifting their emphasis more and more onto those intrinsic attributes. Gone are the days in which free agents earned contracts with their past performance; now, teams pay prospectively for what a player may yet do. In a league in which small edges determine whether a roster is successful or an also-ran, it’s the smart move to focus on what players actually are instead of what they’ve done, and it helps to shed some light on outwardly-puzzling recent signings, like Wheeler’s.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now