This excerpt is brought to you by a partnership between Baseball Prospectus and the Pandemic Baseball Book Club, a collective of baseball authors focused on the principle of cooperation over competition. Check out their conversations about baseball books and much more at pbbclub.com, and on Twitter at @pandemicbaseba1

It was the early spring of 1974, and Glenn Burke was set to begin his third season of Minor League baseball, joining the Dodgers’ Eastern League team in Waterbury, Connecticut.

The ballplayers would be the guests of honor at a dinner that town leaders had planned for them. It wasn’t often that Minor League baseball players felt the need to dress up, but Burke and several of his teammates wanted to look good for the occasion.

Ed Carroll Jr., a left-handed pitcher from California, had no doubts the twenty-one-year-old Burke was the most fashionable member of the team. “If there were forty people walking down the street dressed up nice,” he recalled, “Glenn was dressed flamboyantly nice. You’d know the difference.”

When Burke changed clothes in the clubhouse, teammates noticed he wore colorful Speedo-style underwear while the rest of them wore plain white boxer shorts or jockstraps. Burke always had a stylish cap, tight pants, wide-collared shirts; on occasion he even broke out platform shoes with live goldfish swimming in the clear heels. He was fly, and he knew it. So when Burke invited Carroll to go shopping for sports coats for the team dinner, the pitcher tagged along. Next thing he knew, Burke had convinced him to purchase a gaudy green, yellow, and beige jacket. “It wasn’t me,” Carroll recalled, “but he talked me into it.”

Burke’s influence on his teammates extended beyond their fashion choices. In a tradition-bound game where any display of emotion was taboo, Burke rebelled against the unwritten rules of baseball. When a teammate homered or returned to the dugout after scoring a run, Burke was there to congratulate him in a style he brought from the playgrounds of the East Bay. In an era when simple handshakes or a slap on the butt were the only expressions of joy on the field, Burke shook things up.

“We used to practice this dance where you’d clap your hands up and down, the hand jive,” teammate Marvin Webb said. “We used to do that before games. Nowadays, players have all these elaborate routines they do before games. Glenn and I used to do that back in 1973 and 1974.”

Around the same time as the team dinner, players began splitting into small groups to find houses and apartments to rent for the season. Carroll joined Burke and Cleo Smith in an old Victorian home with “pointy corners” that reminded Carroll of an upside-down ice cream cone. Smith did most of the cooking, winning raves for his fried chicken recipe.

On road trips, Burke and several teammates smoked pot constantly, ignoring team rules against it. On one trip to Canada, the team’s floor at the Hôtel Gouverneur in Quebec City began to reek of marijuana as Glenn and others lit up. As smoke began to fill their room, Webb poked his head out the door when he heard voices on the floor. It was the team trainer, trying to find the source of the telltale odor. Burke and Webb bolted, heading off to a nightclub. When they returned, they noticed all their remaining marijuana was missing. The trainer gathered all the guys who had been staying at that end of the floor, demanding to know who’d been smoking pot.

“I didn’t do it. It wasn’t mine,” Webb said. “You ain’t sending me home because of this.”

“I never did that stuff in my life,” said the next player as Webb stifled a laugh—his teammate looked high even as he denied it.

Then the trainer asked Glenn.

“Yep, that’s my weed,” Burke said without a hint of regret or embarrassment. “That’s my weed and I want it back, too.”

Burke faced no immediate consequences, but his candor shocked his teammates. It was hard enough advancing through the Dodgers’ highly competitive Minor League system to the big leagues without giving the organization a reason to question your character. Most Dodger minor leaguers fully bought into the franchise’s culture and the expectations on and off the field, what was known as the Dodger Way. “We were made to feel proud of our organization, how we were taught to play, that we did things the right way,” teammate Joe Simpson recalled. “We believed we were part of a model organization.”

So, while other players toed the line, it was Burke’s occasional confrontations with authority figures that marked him as an outlier, not his latent sexuality, which he did not yet acknowledge or completely comprehend. His on-field production drew the attention of Dodger executives, but so, too, did his rebelliousness and his ambivalence toward the Dodger Way. This was a big concern for a franchise that liked to portray a squeaky-clean image to the public.

Not that Glenn Burke gave a damn about that. No one could stop him from doing his own thing.

Most of the time, that meant displaying his incredible athleticism on the field. Pitcher Jim Cody remembered the time he gave up a deep fly ball to the outfield (“the hitter just creamed a shot off me,” he recalled) and Cody sprinted behind third base, ready to back up a throw from the outfield on what he assumed would be an easy triple. But when he looked up, Glenn had caught the ball. “I was shocked,” Cody said. “I had never seen anybody cover ground like that.”

Another time, Burke led off an inning and scored a run before the next batter completed his at-bat. Burke had doubled in his first two at-bats of the game, and the opposing pitcher retaliated his third time up by plunking him with a fastball to the hip. Burke rolled around in the dirt in apparent agony, twisting and turning, screaming out in pain. The team trainer came out and asked him to try to walk it off, but Burke took two steps and fell back to the ground. The crowd gasped. Slowly, he dusted himself off and limped to first base. He then proceeded to steal second and third base on the next two pitches. Now standing on third, he darted back and forth, rattling the pitcher, who committed a balk, and the umpire awarded Burke home plate. He’d been faking the injury the whole time, and he relished fooling his opponent to the point of humiliation. “That’s how he could take over a game,” teammate Larry Corrigan recalled. “When he felt like playing, he was explosive.”

But other times, Burke frustrated his teammates with a stubborn indifference. Corrigan remembered a road trip to Bedford, Quebec, a cold, “godforsaken place” where players dressed in dingy trailers, grass refused to grow in the infield—and Burke declined to move in the outfield. As they stood around shagging fly balls during a chilly batting practice session, Burke turned to Corrigan. “This has been a horrible road trip,” he said. “I don’t even feel like playing.” “Well, you have to play,” Corrigan pleaded. “I’m pitching tonight.”

Corrigan got his wish; Burke started the game in right field. Meaning, at least he stood there. Corrigan gave up a single to lead off the game, and then the next batter followed with a hit-and-run single that rolled into the outfield a few feet to Burke’s right, slowly bouncing past him. “He never moved an inch toward the ball,” Corrigan recalled. “Not an inch. That was Glenn.”

And then there was The Brawl. Ask any member of the 1974 Waterbury Dodgers about that otherwise unremarkable season, and they’ll all ask if you’ve heard about the fight. Some of those players advanced to the major leagues, fulfilling boyhood dreams. Others never progressed any further in the minors, Waterbury once and forever the high-water mark of their pro baseball careers. But regardless of the trajectory of their lives in baseball, The Brawl in Quebec City stands alone as a bizarre, violent, and comic illustration of the machismo, competitiveness, and unrefined nature of Minor League baseball and Glenn Burke’s place in that world.

There was bad blood between the Dodger and Expo minor leaguers dating back to the standoff a year earlier in Daytona Beach, Larry Parrish accused Burke of spitting on him. Players on both teams brought that baggage with them to their Eastern League teams in Waterbury and Quebec City in ’74; both sides prepared to resume the fight at the slightest provocation.

Placing Glenn Burke anywhere near a powder keg was the surest way to provoke an explosion, and that’s just what happened in this early April game under sleeting skies in Quebec.

John Snider, playing third base for Waterbury, was due to lead off the top of the seventh inning in the Dodgers’ batting order. After Quebec made the third out to end the sixth, Snider ran into the dugout to put on his helmet and grab a bat from the rack. As he fastened his batting glove, he looked out at the field and saw Burke standing on top of the pitcher’s mound, the last place he should’ve been at that moment, staring and screaming into the Quebec Carnavals’ dugout along the first-base line.

Given the tensions already crackling in the frigid air that night, Snider knew this episode would not end well. The Quebec pitcher had thrown a fastball near Burke’s head to lead off the game, sending an unmistakable message that his team was ready to fight. As Burke had patrolled right field throughout the game, Carnaval players peppered him with insults. After playing catch with the Dodger center fielder before the bottom of the sixth inning to keep his arm loose, Burke was supposed to throw the ball across the diamond back into the Dodger dugout, as was custom. Instead, he rifled it straight into the Carnavals’ dugout along the first-base line, startling his heckling opponents and igniting a new round of taunts. And now there he was, standing on the pitcher’s mound trading verbal crossfire with the home team.

“Why don’t you come out here if you want to do something about it?!” Burke screamed, and the Carnavals took him up on the offer, sprinting out of the dugout. Before Burke’s teammates could make it out to the field to join the fisticuffs, Burke had already decked the Quebec pitcher, knocking him straight to the frozen infield like falling timber. By then, Burke’s teammates had rushed the field, some players throwing punches, others trying to break up the fight. Dodger pitcher Ed Carroll Jr. and manager Don LeJohn tried to calm things down, standing between an enraged Burke and the Carnavals, but Burke simply reached over them and smacked a Quebec player right in the face, sending him tumbling to earth.

Next, Carroll made his way over toward the Dodger dugout, where another fight had broken out. Dodger Cleo Smith had stepped down into the dugout to grab a bat, and Larry Parrish stood outside, daring him to come out and fight with just fists, no bats. Smith obliged, and Parrish threw a punch as Smith ascended the dugout stairs. Smith, a former teen boxer, ducked just in time, popped back up, and responded with a right hook to Parrish’s jaw, sending Parrish sprawling over a three-foot railing into the stands. “And don’t you come back out here!” Smith yelled.

By this point, mini skirmishes had broken out all over the field, like brushfires on the plain, and Quebec fans had joined the action, screaming French epithets the Waterbury players didn’t understand and dumping beer on the players battling near the grandstand. Dodger players responded by hurling bats at the fans. Meanwhile, Carnaval outfielder Ellis Valentine socked Dodger catcher Dennis Haren in the face, opening up a cut from the side of his mouth clear to his other ear. Haren felt a gash between his nose and upper lip, and pulled a tooth out of it. Dodger pitcher Bob Lesslie saw Haren writhing on the ground and ran over to pick him up, but just as he arrived, Quebec’s Tony Scott yelled, “You want some, too?” and hit Lesslie with an uppercut to the face, knocking out his two front teeth.

Finally, all the players were either knocked nearly unconscious or exhausted from all the punching. LeJohn considered it the biggest fight he’d ever seen in twenty-one years in pro baseball.1

Glenn Burke, the guy who had started it all, stood triumphantly in the center of the mayhem, like the last pro wrestler standing after a battle royal, having punched two guys out cold and suffering not a scratch.

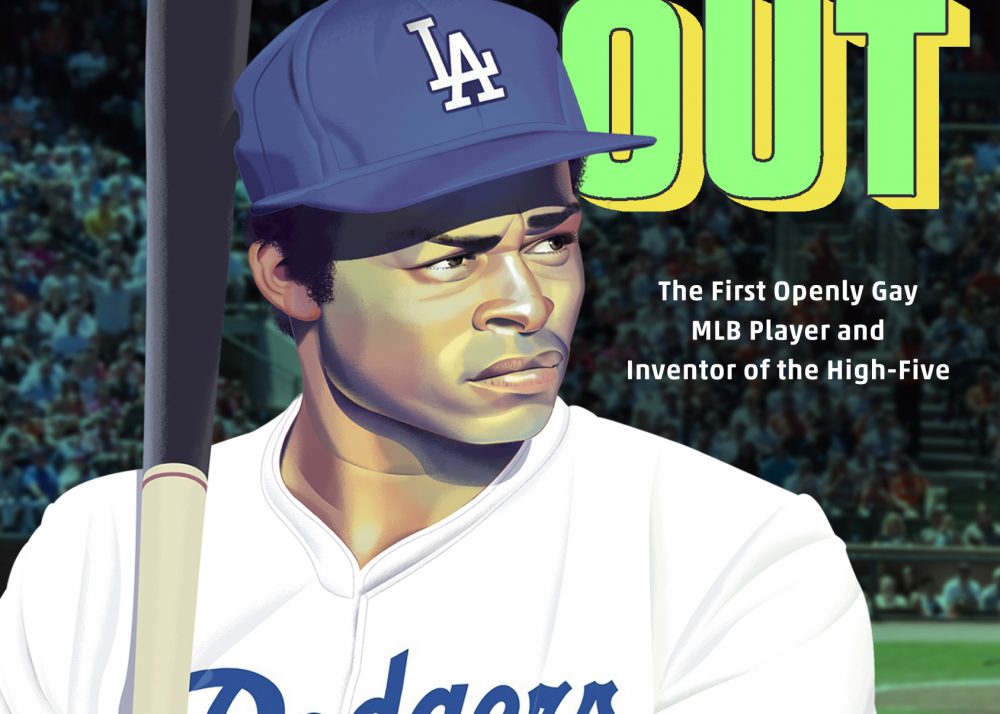

Excerpted from SINGLED OUT: The True Story of Glenn Burke, by Andrew Maraniss (c) 2021. Follow Andrew on Twitter @trublu24 and read more about SINGLED OUT and his other books at www.andrewmaraniss.com.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now